Gold! This was the quest of not one, but two expeditions that crossed Vancouver Island from east to west during the mid-nineteenth century – both from Cowichan Bay and along the river of the same name – to Kaatza (meaning the “Big Lake” in the Hulqu’mi’num language) and beyond in search of the elusive metal.

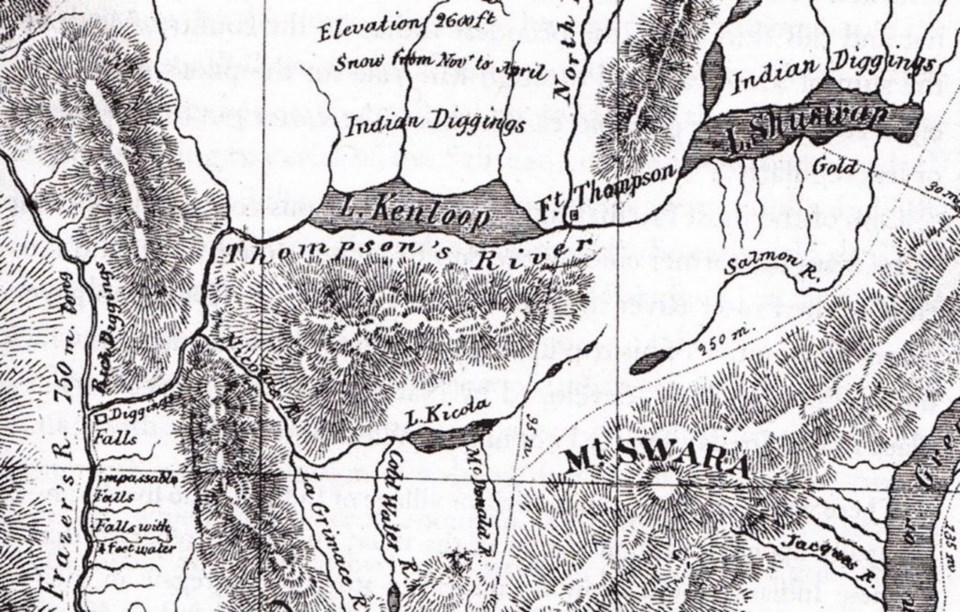

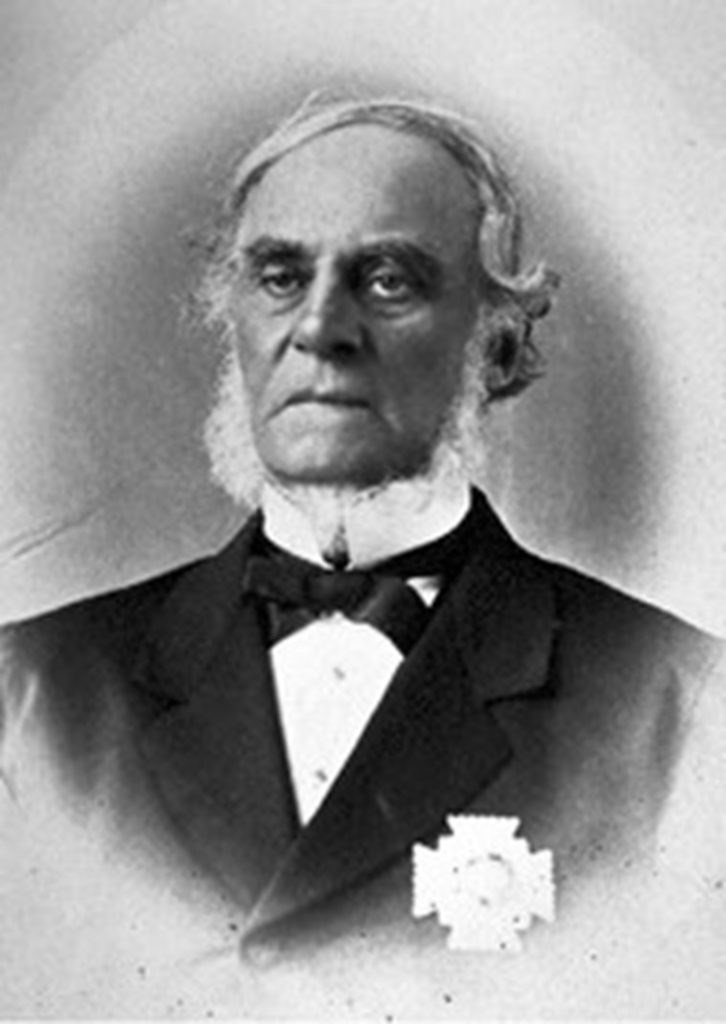

When the first “Indian diggings” were confirmed by Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor James Douglas in the Interior of what would become British Columbia (a year or two before the 1858 Fraser River gold rush) he soon began to wonder whether gold might also be found in Vancouver Island.

Certainly, there had been a limited gold rush to Haida Gwaii in the 1850s, but no serious gold reconnaissance of Vancouver Island by non-Indigenous exploring parties, even though the founding of the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1849 had been the direct result of the massive California Rush of the same year.

While Douglas, also Governor of Vancouver Island, was excited by discoveries on the Mainland, apparently most were not! The Governor’s son-in-law, Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, recalled:

The Governor attached great importance to [those mainland discoveries] . . . and thought it meant a great change and a busy time. He spoke of Victoria rising to be a great city — and of its value, but curiously enough this conversation did not make much impression.”

Some few weeks later, Douglas was again to show further gold collected by the Nlaka’pamux Indigenous people, this time “a soda-water bottle half full of scaly gold,” yet Helmcken recorded that the Vancouver Island House of Assembly “took no heed of these discoveries.”

As Speaker of the Colonial Legislature, Helmcken’s words show just how far removed the officials of the small colonial outpost were from the mainland discoveries that would ultimately reshape the coast. Nevertheless, Douglas remained undaunted and soon found reason to mount an expedition to cross the Island in search of gold.

According to one member of the expedition, Lieutenant Sherlock Gooch (son of Vice Admiral Thomas Lewis Gooch, grandson of Sir Thomas Sherlock Gooch, 5th Baronet, MP), shortly before sunset, 2 September 1857, the expedition aboard HMS Satellite steamed into Cowichan Bay, and anchored near the mouth of the Cowichan River.

A few hours later she was joined by the Hudson's Bay Company steamer Otter, having on board His Excellency James Douglas, Governor of Vancouver's Island.

Apparently, the stated object of Douglas’ visit to Cowichan was to confer with the Somena Indigenous people (a tribe of the Cowichan Nation). Only much later would it become known the governor had an additional, hidden motive.

The following day Douglas, accompanied by several naval officers, HBC officials, and an escort of 50 seamen and Royal Marines, traveled up the river for the ancient village of the Somena people. According to Gooch:

The entire tribe turned out to welcome the Governor. They were not demonstrative, but were undoubtedly pleased to see Mr. Douglas. This remarkable man was a born administrator, and his name was held in fear and respect by every tribe on the north-west coast of America.

The chief had words with Douglas, and apparently the governor had responded in their own language, the exact communication not recorded by Lieutenant Gooch.

The chief of the village, “a handsome, well-set-up, and dignified man of about thirty-five” led the official party to camp about two miles further to an open campground with Swuq'us (meaning “dog” and related to an ancient Cowichan story) or today’s Mount Prevost looming in the distance. Here was established the governor’s base camp. Apparently “ponies” had also been shipped in from Victoria to use in their explorations of the valley’s agricultural potential (perhaps an ominous sign for the local Indigenous peoples). Gooch’s account becomes further interesting as to Douglas’ hidden intention.

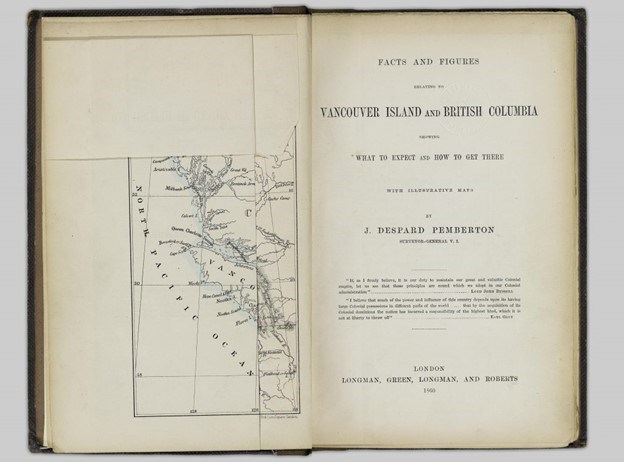

Late this evening (September 4th) Mr. Joseph Pemberton, Surveyor-General of the Colony, accompanied by two young Americans and an Iroquois in the pay of the Hudson's Bay Company, and several Somanos [sic] Indians to act as porters, left the camp without the knowledge of any of our party, except the Governor, with the intention of crossing the Island to the Pacific side. It was not generally known, but Douglas knew that gold had recently been discovered on the mainland. He wished to quietly ascertain whether it also existed on the Island. Hence the attempted secrecy.

Before the expedition was underway the Somena people, many apparently hired as packers, abandoned the project. This shortage of people led to Royal Marines like Lieutenant Gooch to immediately enlist. This was 1857; the smallpox epidemic of 1862 had yet to sweep the coast. Indigenous populations, such as the Cowichan, were not only numerous, but had already taken more than one determined stand with the colonial government – which had not engaged in any treaty-making in the Cowichan Valley, as in Southern Vancouver Island.

History records that the Cowichan people were naturally aggrieved they had not been paid for their traditional lands, and though the larger settlement by non-Natives was yet to occur five years later (with the arrival of HMS Hecate), it seems likely that Douglas would have been confronted on this issue, and a reason for the Somena to abandon their support.

Whatever the reason, from Somena intelligence colonial authorities learned of the existence of “a large lake in the centre of the Island” and this became the expedition’s first goal – to find Kaatsa.

As Pemberton’s party headed up through the Cowichan River-lands for the “unknown” lake, the story is of tough terrain, travel, weather and hardships:

“Through thick masses of wild raspberry bushes and other underwood . . . With our packs and our rifles it was a scramble getting down,” admitted Gooch, “but at last, with torn clothes and bleeding hands, the lowland was gained.” Yet through it all they continued to look for gold:

“Some ravines, with torrents from the north, were crossed, and in the beds of the streams gold-bearing rocks were found, and specimens obtained.”

Governor Douglas would have been pleased.

The expedition was undoubtedly at a great disadvantage without the Somena to not only pack for them, but more critically, to guide them. What success they did have was aided immeasurably by one mixed-race individual by the name of Tomo Antoine, the legendary Iroquoian hunter and HBC interpreter. Gooch described this extraordinary individual:

As Antoine was an important member of our party he deserves a description. About forty-five years old, he was a slight, actively built man, with a dark, copper-coloured face, lit up by keen, intelligent blackeyes. . . By birth an Indian of Lower Canada, he spoke the French dialect of that province well, and also English, and many Indian languages. His reputation as a huntsman and axeman stood high, and from his intimate knowledge of back wood life and of the customs of Indian tribes Antoine was a valuable addition to any pioneering expedition in North America. Further, although of a rather suspicious and peppery temperament, the Iroquois was a cheerful, sociable fellow, and spun us many amusing yarns when seated round our campfire at night.

The “Tomo” referred to here is none other than Thomas Quamtany, one of Douglas’ most-favoured interpreters, employed in this role at Fort Victoria through the treaty-making councils of the 1850s.

After further hardship and toil the expedition party finally “had their eyes gladdened by the sight of a large sheet of water glistening in the rays of the setting sun,” wrote Gooch.

“This was at once pronounced to be the great central lake described by the Somanos Indians.”

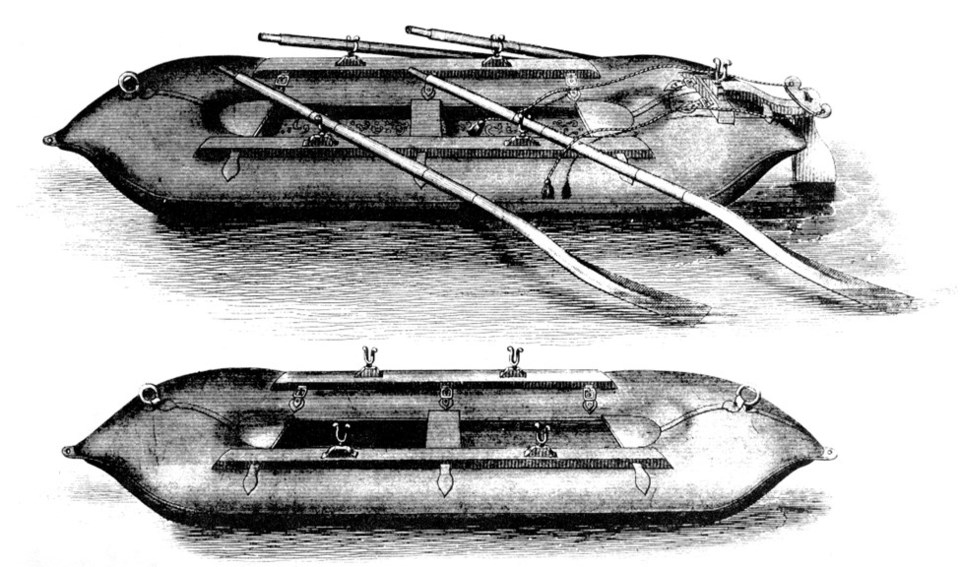

Glad to leave the bush, the exploring party set out to inflate a 30 foot “Indian rubber boat” – surely the first such inflatable boat to have ever been used in British Columbia. “It was blown out, duly named the Pioneer, [and] launched on the waters of the Cowichin.”

Pemberton’s party also “spent eleven hours” building a sizable raft which they named the “Saucy Jack” and both these craft were put into play exploring the great inland lake of Cowichan.

The expedition surveyed the surrounding countryside, eventually making it to Nitinat and the West Coast of the Island, but no further mention of gold discoveries. Reporting to Douglas 12 November 1857, Pemberton wrote:

The principal instruments and chronometer I carried myself, but as the country is heavily timbered, after passing Mount Prevost, and the fallen trees slippery to walk on, occasional falls was a thing unavoidable, which so damaged the instruments that I regret to say the observations, though taken with the utmost care, proved useless, and the map annexed a compass sketch.

And as to gold, the object of the original secret mission, all the Pemberton Report could say was “Gold-bearing rocks are met with in the mountains” and “trusting that the circumstances mentioned in the earlier part of this report will somewhat excuse its incompleteness.”

So ended the first attempt by non-Natives to cross the interior of the Island in the pursuit of gold. Douglas would have undoubtedly been disappointed; the expedition had been launched with great fanfare and at considerable cost.

While the HBC had already staked claim to coal reserves at places like Suquash and Fort Rupert in northern Vancouver Island (and subsequently Nanaimo), significant gold discoveries remained outside the jurisdiction of the Colony, and entirely within the Indigenous country lands of mainland New Caledonia – the HBC fur trade world as yet reconstituted the Crown Colony of British Columbia. Undoubtedly, here was another motive for Douglas, as Governor of the separate Colony of Vancouver Island: to essentially assert sovereignty over the Mainland in advance of any authority from Britain.

Seven years would transpire before another attempt was made to cross the Island from Cowichan to Nitinat, and as before a hunt for the elusive gold. But by this time Governor Douglas had retired, a new governor presided, smallpox had overwhelmed the Cowichans (their reduced numbers a justification for subsequent reserve land reduction). This next crossing was the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864, the subject of Part II of this series - tomorrow morning.

Read Part 2 here.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Last month, Daniel Marshall returned to The Orca with a personal family story of war, loss, and the terrible cost even paid by the survivors.

- Daniel Marshall was one of Rick Cluff's earliest (and best!) guests on Off the Cluff.

- May Q. Wong told the incredible story of Vancouver Island's all-black militia.