Editor's note: Don't miss Part 1.

Gold! This was the quest of not one, but two expeditions that crossed Vancouver Island from East to West during the mid-nineteenth century.

While the 1857 reconnaissance had met with indifferent results, the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864 achieved much greater success, particularly in its search for gold – and this time with the active participation of Chief Kakalatza [Kakalatse] of the Somena people.

The expedition followed a similar path to Cowichan Lake, under the command of Dr. Robert Brown, a young botanist, who awarded Chief Kakalatza special recognition. In Robert Brown and the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition (1989), John Hayman notes Chief Kakalatza’s importance to the expedition both for his intimate knowledge of the river landscape through which they traveled, and also for the ethnographically important stories shared with members of the expedition:

Brown’s most rewarding period as a collector of myth and legend [notes Hayman] was probably during the four months of the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition in 1864, and he was later to acknowledge his indebtedness to. . . Kalalatza, a joint chief of the Somenos [Somena] who accompanied the exploratory party from Cowichan Harbour to Cowichan Lake. ‘Every dark pool suggested a story to him,’ Brown remarked, ‘every living thing had a superstition, and hour after hour we lay awake listening to the strange story of Kakalatza, Lord of Tsamena.’

I know descendants of Kakalatza [Kakalatse] today, proud to know the story of their famous ancestor. Yet, there is another pivotal expedition member: “Tomo, who joined the expedition at Cowichan Harbour and remained with it until the conclusion.” Tomo (Thomas Quamtany) was the only individual to have accompanied both expeditions in 1857 and 1864. As noted previously, Tomo was a mixed-race guide and interpreter considered by Governor Douglas to have been indispensable in so many early explorations.

The Brown expedition left Victoria by boat on 7 June 1864, and arrived at Cowichan Bay that same day. On 9 June they left the village of Comiaken and arrived at the "Great Cowichan Lake" on 15 June. Of the river, Brown wrote:

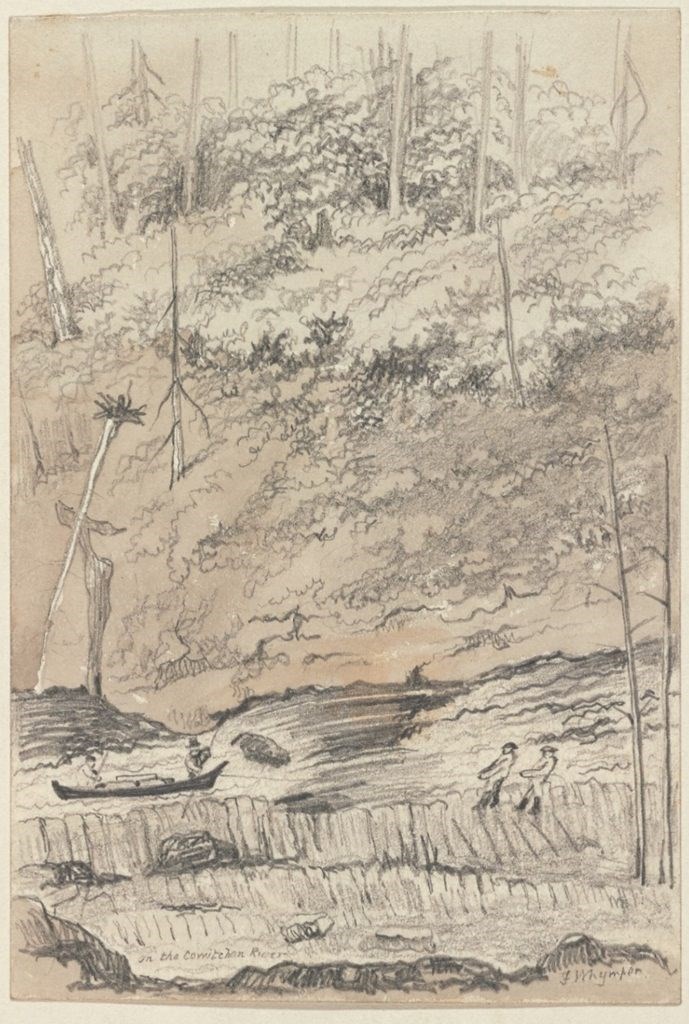

The Cowichan River is about 40 miles in length, and is a most tortuous stream; a straight line from the mouth of the lake would not probably be more than 29 miles; it is exceedingly rapid, there being hardly any smooth water with the exception of short distances in the canyon, and about two miles at the height of the river before joining the lake. Its banks, some distance from the sea where the sea breezes do not affect them, covered with magnificent forests of the finest description.

And as to the existence of gold, Brown provided much more detail than Pemberton’s problem-plagued expedition of 1857:

The color of gold we found everywhere, and in one or two places from X cent to IX cents to the pan was reported to me, in other places sufficient pay dirt to last for a long period. I may call to the recollection of the committee that white men have since then been-reported as making as much as $5.00 per diem on this same river.

In addition, this expedition was now able to collect identifiable Indigenous names at every point, Chief Kakalatza pointing out to Brown himself the long-time place-names found throughout the river corridor:

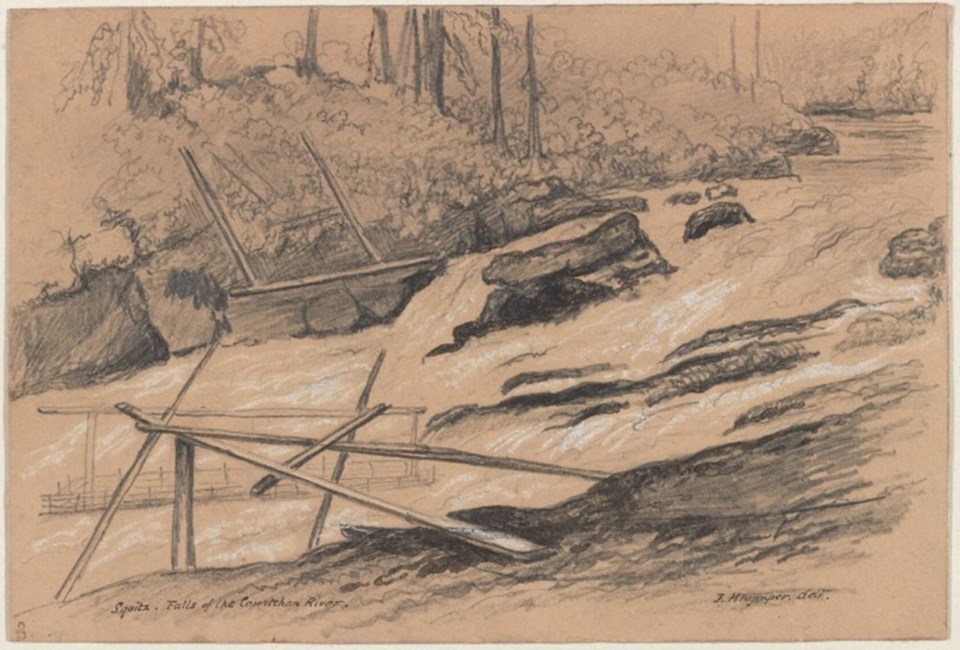

A trail is here and there found along the banks with occasional fishing lodges, [wrote Brown] and camping ground such as (above Samena), Tsaan (the 'torn-up place'); Saatlaan (the place of 'green leaves'); Klal-amath (two log houses); Qualis (the 'warm place', Latitude 48 degrees 45 min. 37 seconds north); Kuchsaess (the 'commencement of the rapids'); Quatchas (the canyon); Squitz (the 'end of the swift place'), a most picturesque series of rapids with Indian lodges of which we secured a sketch, and so on until we came to Swaen-kum, an island where the Indian deposits the poles by which he has hitherto propelled his canoe up the rapid stream for now we have come into Squakum, the still waters, the commencement of the lake, where the current is no longer perceptible...

On Friday, 10 June 1864, Brown took steps to commence the expedition:

Sent the canoe with Tomo, Kakalatza, Lemon [son of Comiaken Chief Locha], in charge of Mr. Buttle, up the River with the provisions, appointing an Indian fishing village called Saatlaam as the rendezvous, the exact situation of which had been described to me by Tomo & said to be reached by tolerably good Indian trail. To lighten the canoe each of us took our personal [belongings] though this was somewhat compensated by the amount of personal baggage Kakalatza took—amongst others his hat and incredible to say a hat case to hold it which he had got from some young Englishman who had ‘gone through the mill’ in Cowichan since the halcyon days of Regent Street. His villagers gathered out to see him off. He wished to take one of his young men with me but I declined. With the rest of the party I started off, taking with us an Indian boy Selachten to put us on the trail.

The exploration having begun, Brown remained alert to any information about gold:

On a creek a little further up, gold has been found in paying quantity it was said by Mr Jas. Langley who prospected it in company with Harris & Durham in 1860 [following Pemberton’s confirmation in 1857], but we now know better what pay [is] in placer diggings & I am assured by Harris that it would not pay. It yielded according to our washing about 8 colours to the pan, but I have no doubt but that more could be got.

Not unlike the earlier Pemberton Expedition, Brown’s party were often “losing the trail frequently and tearing our hands & feet through thick undergrowth of crabapple & raspberries.” And sometimes when he inquired of the Indigenous name of a particular locale, it was so ancient that “the meaning we could not learn, as it was named in days long gone by, by the old people from something they could not understand, just like places in our own country.”

Unlike the Pemberton Expedition, the 1864 exploration sought more than geographical information or intelligence of gold. Tomo, like Kakalatza, often spent the evenings in camp telling stories – undoubtedly like those told to Lieutenant Gooch in 1857, but the difference was that Brown recorded them.

Moonlight night—late to rest—stood round the camp fire listening to Tomo's description of Indian astronomy and was struck with it as similar to the Arabian in the similitudes they draw between constellations and known objects. The handles of the plow are two men in a canoe, the Pleiades are a collection of fishes, Four stars (The Plow?) are an elk. The Moon they think travels and has a frog inside of it (Is this worse than our Man in the Moon?) The stars are little people. A strange people are these Indians. The more you know of them the more can you appreciate their shrewdness—the curious store of lore and traditions they possess; to judge them as you see them ‘loafing’ about the white settlements is like judging a man by the coat on his back. Few ever take the trouble to learn about them and still fewer know anything bad about them tho' loudest in their general dogmatic denunciation of them.

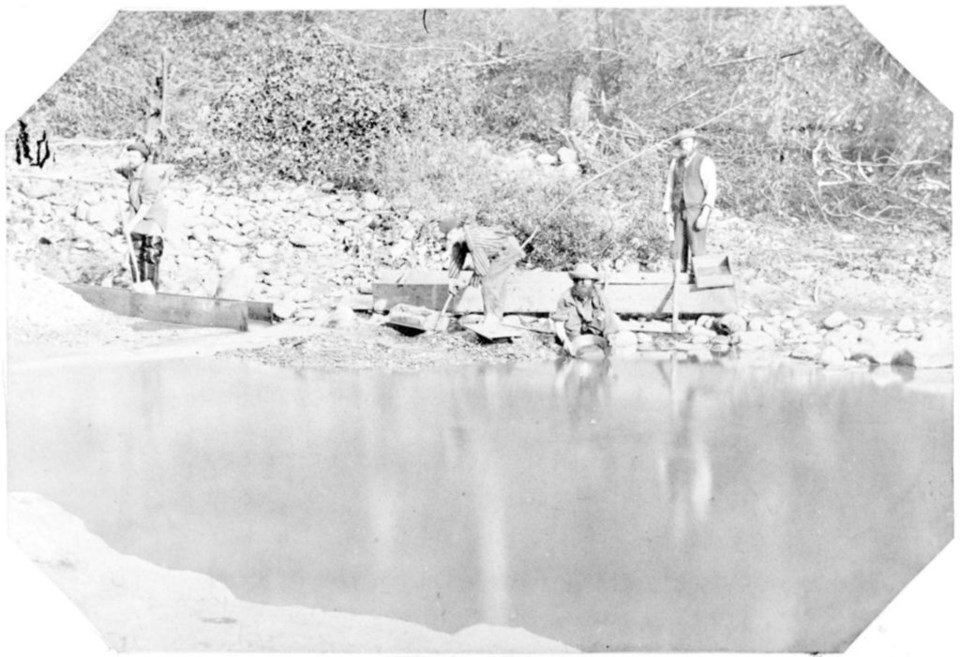

As the party continued up the Cowichan River, gold was never very far from their minds. The expedition even employed an experienced American gold seeker who was constantly dipping his pan into the various streams and sand & gravel bars they encountered. In fact, American gold seekers often played a pivotal role in the early development of this province.

Brown wrote of this experienced gold miner:

Foley (a very experienced Miner) prospected a bar & found about 1/2 cent to the pan & thinks pay might run ahead of the prospect and that Chinamen [archaic] might by using Blankets and quicksilver make $1 to $1.50 per diem which would be a great thing for the country. On every creek and bar yet we have found the colour of gold and plenty of black sand but too fine. Hitherto the River has been bordered by flats (more or less wooded) & it is not likely that good prospects can be got on bars in their vicinity. What gold comes down the hills lands on the flat where an equally good prospect can be got. When the hills come down to the water that is the time for prospects.

As the expedition continued to map and record their journey, heavy rains compelled them to take shelter in two native lodges at Skutz Falls shown to them by Kakalatza. “These lodges were empty just now,” recorded Brown. “Three young men & two women having gone (so old Kakalatza said) to hunt elk at the great Lake. We accordingly took possession of the best lodges—& as our trousers were very wet, we took them off & fastened our blankets round our legs Indian fashion & stretched our length upon mats belonging to the ‘three hunters of Kaatsa’ in which position Mr. Whymper took a rough sketch of the party.”

Though the rain continued unabated, Tomo continued to hunt and bring fresh game, and the expedition continued the next day, Tuesday, 14 June, in the direction of Lake Cowichan.

“Now we appreciate our waterproof sheets,” Brown commented on the deluge they had experienced, “It seemed true as Macdonald [an expedition member] declared that ‘the devil was whipping his wife’ &, if we may judge from his frequent allusions to that gentleman, he appears to be on terms of considerable intimacy.”

The American miner Foley continued to prospect throughout, next panning “an old bar & found 1 cent to the pan, fit to pay a good miner with a rocker $2.50 to $3.00 per day. It is on the old bars of the river that we have found the best prospects & hence the best gold.”

To give these wages some perspective, standard pay for a labourer at the time was about $1 per day. Brown recommended for the future that “men who have the means & the inclination with appliances superior to ours, & more time at their disposal, to test further a river which we have proved to yield more gold than any other place yet tested in Vancouver Island.”

Brown was convinced of their success:

Foley is a very experienced Californian & British Columbian Miner & may be relied on. I particularly cautioned him against the slightest approach to exaggeration, telling him that I was not at all anxious to swell out my report with reports of gold but only want the naked— even underestimated—statement of the truth. He assured me that he had gone under rather than over, when he stated the prospect at from 3/4 to 1 cent the pan. A very experienced miner can wash out 300 pans a day. Call it $2.00 a day. I saw many Chinese on Fraser River last autumn between Lillooet & Yale—particularly about the far-famed Boston Bar weighing out their day's earnings, and dividing from 55 cents to $2.50 to each—& yet they were contented, notwithstanding the privations of these out of the way places, & the high rate of provisions.

“So exciting is gold hunting,” enthused Brown, “that men are willing to leave the certainty of good wages to take the uncertainty of poor ones, led away by the hopes of striking large ones. Nothing but this could ever make them endure the hardships & disappointments of their work.”

Finally, Brown’s party approached Lake Cowichan, and in a little clearing somewhere before the lake “found on a cedar tree divested of a piece of the bark, written in pencil fresh as the hour its being written ‘Harris, Langley & Durham Augt 1st/6o’ marking the limits of their exploration. We added our autographs to this memorial tree.”

Just beyond, Chief Kakalatza was waiting with their canoe and about a mile further along were greeted by “a blazing fire” where other expedition members were found busy cooking supper, “which we soon encircled to dry & warm ourselves, until the heat made us retreat to a respectable distance from it.”

Brown recorded:

The Indians say ‘You White Men are fools. You build a fire to warm yourselves but you make it so big that you cannot get round it,’ & I daresay they are quite correct. A White man's camp you can know for years. He cuts down trees, he heaps on logs, & altogether he makes a very ‘tall’ fire, but the Indian manages things better, & saves himself a great deal of trouble. He gathers a few sticks, saves his axe, makes a small fire & crowds round it, warming without burning themselves.

In short order the expedition would travel the great Lake Cowichan (Kakalatza soon returning to Somena having fulfilled his promise to guide them to the lake). They inspected the vast terrain, sampled the creeks for gold, and ultimately ventured to Nitinat on the West Coast, but not before breaking into two separate parties.

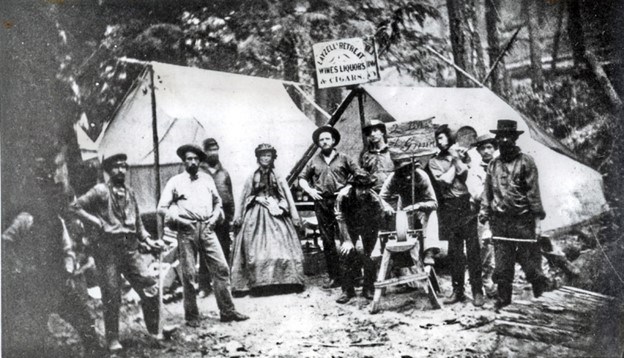

Under the command of Lieutenant Peter Leech, Royal Engineer, the breakaway party headed down into the Sooke Lake watershed and finally struck the kind and amount of gold that Governor Douglas had so hoped for – the Leech River, a tributary of the Sooke River – and some of the coarsest gold yet found. With this discovery, the Island’s own gold flurry commenced – the Leech River gold rush – but some six years after the Fraser River Rush of 1858.

The Leech River gold fever was immediate. Before the year had ended, there were a total of six general stores, 30 saloons, and about 1,200 miners in these goldfields.

How gold has – and continues – to change the world. Between 1857 and 1864 not only had a smallpox epidemic hit, an instant gold rush town created, but increased numbers of non-Native settlers had moved into the Cowichan Valley. While Robert Brown’s expedition had been a success, for Indigenous people it represented vastly more than a mere mixed blessing. Throughout the 1864 journey Brown had widely conversed with the Cowichan people and recorded the substantial ill-effects to their people. Writing at Cowichan Bay, 9 June 1864, “The Indians are complaining of the conduct of the whites,” wrote Brown.

They say ‘You came to our country. We did not resist you – you got our women with children & then left them upon us – or put them away when they could have no children to keep up our race (a fact or nearly amounting to as much). You brought diseases amongst us which are killing us. You took our lands and did not pay us for them. You drove away our deer & salmon & all this you did & now if we wish to buy a glass of firewater to keep our hearts up you will not allow us. What do you white men wish?’

This is in part very true. The Indians have not been treated well by any means. There is continually an empty boast that they are British subjects, but yet have none of the privileges or the right of one. Their lands have never been paid for in these districts at least. They are not taxed nor yet vote. They are confined in their villages to certain places. Nor are any means taken to protect their rights of fishing & hunting.

Over 150 years since a sympathetic Brown itemized the complaints of the Cowichan peoples, and in 2020 it still remains that “their lands have never been paid for.”

While Pemberton and Brown would have their names immortalized in history, the success of these two colonial exploratory parties depended quite significantly on others less well known: Chief Kakalatza; and Thomas Quamtany, a.k.a. Tomo. They certainly warrant inclusion, indeed a much more prominent place, in the history books of our province – in addition to the outstanding grievances of these Indigenous people of the last one and a half centuries.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Don't miss Daniel Marshall's ripping good yard (and 100% true) of a holiday adventure story: Lost in the Mountains on Christmas Day.

- Daniel previously told the story of the HBC interpreters who quietly became indispensable, and influential.

- Jody Vance is worried a crucial plank of Lower Mainland culture might just become history.