For the last year or two I have been working with Cowichan Elders assisting them with the translation of their stories from the Hul’qumi’num language (the Island dialect of Halkomelem, Coast Salish) to English. These include some of their earliest foundation stories of a people whose ancestors – it is said – fell from the sky.

What a privilege it has been to meet with them a few times per month, fuelled by cups of tea and the occasional “culture break” – code for a smoke…yes, I still smoke, darn it.

While we ease into preparing to listen to the next recording, there is nevertheless a sense of urgency; these four Indigenous Elders are some of the few remaining speakers of their traditional language, and yet at times there is simply no English equivalent that conveys the subtleties of certain words in their language.

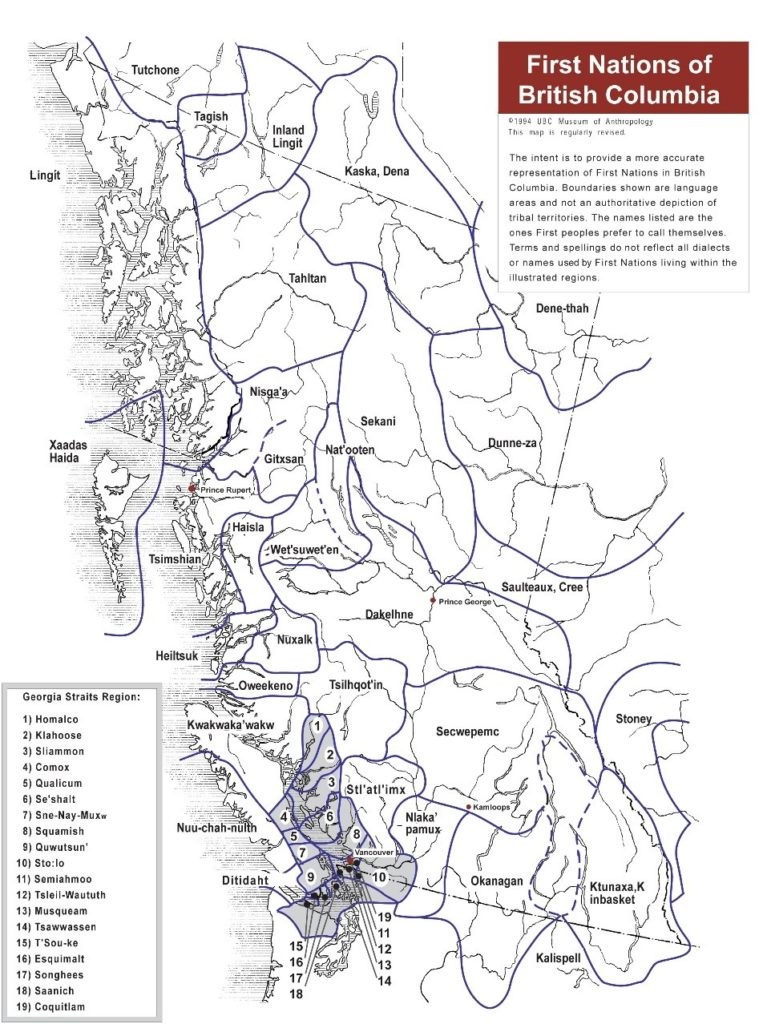

The place we now call British Columbia is considered one of the most culturally diverse regions of the Americas (second only to California) – and here I am talking primarily about the multitude of Indigenous languages, due to the fact that BC is on the ancient highway that peopled the Americas. Europe might be a close basis of comparison for similar cultural diversity.

“Is there a word for that in English?” I quite routinely ask, at times rather sheepishly. After all this time together they more often than not respond with bemused silence. Once we’ve had a good laugh, we get down to searching for some close equivalent that might capture the essence of the Cowichan word being discussed.

And so, as an historian, this got me thinking about what it must have been like trying to communicate with Indigenous nations and allies during the fur trade era – these first Native-newcomer encounters – and wondering just how much got lost in translation?

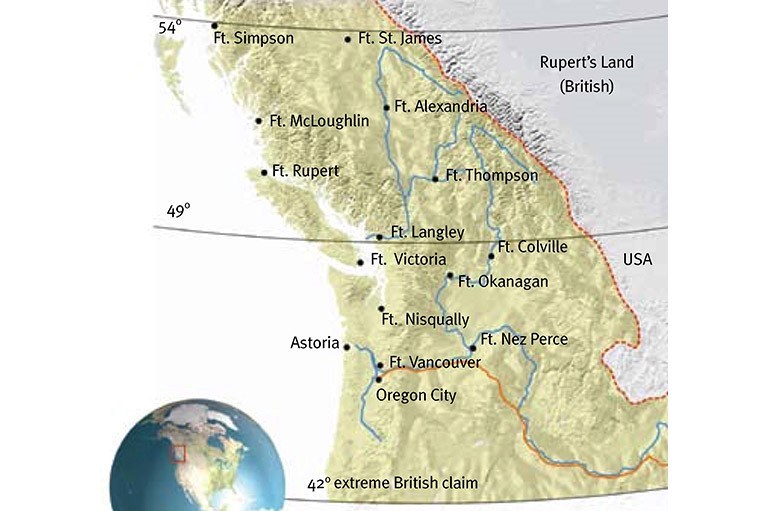

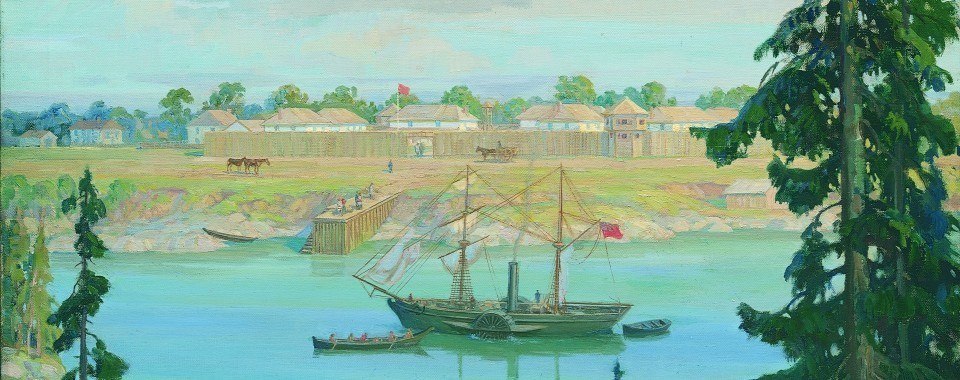

The use of linguistic interpreters has a very long history in Canada, especially by the Hudson’s Bay Company (established 1670). There is a centuries-old history of communication and relations with Indigenous peoples in which clear conversation was paramount to establish forts within Indigenous territories, hire Native labour, trade, and strengthen relationships through intermarriage.

As fur trade historian Richard Mackie has asserted, HBC’s success came from grafting company operations onto extensive, pre-existing Indigenous trade networks. In the early years before the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia were founded, the fur trade corporation also seemingly had worked within pre-existing systems of Indigenous law.

Let’s remember that there would not have been any fur trade in BC or Canada without the key participation and consent of Indigenous peoples. To further these early trade relationships, the HBC also worked within the myriad of Indigenous languages found east of the Rocky Mountains.

In BC, improving Indigenous language skills and the collection of Native vocabularies was not only a common practice for HBC personnel, but of utter necessity. The diary entries of Dr. William Fraser Tolmie (see Physician and Fur Trader: The Journals of William Fraser Tolmie), written from Fort McLoughlin, contain multiple instances of recording Indigenous languages. Here are some to consider:

| Friday, February 21 [1834] | “Visited by several parties of Indians . . . Rec[eived] from one several Bilbilla [Bella Bella] words. Have tonight been arranging & putting in a portable form a vocabulary given me by Mr. Dunn & purpose making additions to it tomorrow.” |

| Saturday, February 22 [1834] | “. . . made considerable additions to vocabulary.” |

| Sunday, May 11 [1834] | “A party of Billichool [Bella Coola] arrived & from the Chief Nooshimald I obtained a brief vocabulary of their language, it resembles at most word for word that of the tribe [Alexander] Mackenzie met with on this coast & they are probably identical.” |

| Sunday, July 20 [1834] | “I entered an office of Indian Trader & procured a vocabulary of the language of this tribe – the Chimmesyan [Tsimshian].” |

| Friday, July 25 [1834] | “Busy trading cedar bark during forenoon, assisted in communicating with the natives by an Indian who understands the Milbank or Haeeltzuk language of which I acquired a slight knowledge at Fort McLoughlin.” |

| Monday, December 29 [1834] | “The dialect of the Kitamats does neither resemble the Chimmesyan nor that of the Haeeltsuk – in pronunciation it approaches more to the former, but in the form of the words to the latter, indeed it is similar in many words.” |

| Wednesday, January 7 [1835] | “I have to . . . . arrange in a tabular form the different Indian languages of which I have got vocabularies.” |

| Tuesday, April 21 [1835] | “Yesterday & today occupied in making a vocabulary in a tabular form of the different Indian languages of which I have collected words – they are the following – Nusqually, Noosclalom, Haeeltzuk, Billichoola, Gueetilla or Nass, Haida or Queen Charlotte’s Island & Tumgass or Kittichunnish. Have had a Nucelowes & Milbank Indian giving me the words of their proper languages.” |

Clearly, more was being spoken than simply Chinook Jargon (the composite trade language of the 18th and early 19th century maritime fur trade) in these early cross-cultural encounters. HBC employees such as Tolmie were effectively responsible for perfecting such communications through ongoing studies of Indigenous languages.

The HBC was well aware of the need for good interpreters. Formally-appointed staff positions for the role of “interpreter” were common to all HBC fort operations. When on those rare occasions an interpreter was unavailable, the results were deemed incredibly disadvantageous to HBC operations. For example, Archibald McDonald, writing from Fort Colvile to Chief Factor John McLoughlin on 8 August 1842, stressed the importance of company-employed linguists. Attacked by Native peoples through some misunderstanding, he blamed the company’s recent cutbacks in interpreters as the main cause:

It was an ugly affair as it was, but had very nearly gone the length of something more disastrous in the helpless condition we were in with our property exposed along the rapids, & worse still with not a man of the party able to speak two words of the language to bring us to a better understanding. I mention this last circumstance seeing so little is made of the young linguists brought up in the district, all now I understand ordered away as a useless burden on the Establishment. Let the maxim never be lost sight of among Indians that much mischief can be prevented by a timely & proper understanding of existing difficulties, which in the absence of such simple explanations it might take years of main strength to correct, & then after all in nine cases out of ten we only come off second best. Interpreters are a necessary evil.

Hopefully the Elders I work with do not see me as a necessary evil!

A quick check of existing fur trade literature shows, time and again, that interpreters were employed throughout as salaried staff formally appointed primarily for their linguistic abilities. HBC employee Joseph McKay recalled that “Most of the intercourse with the Indians was carried on through the interpreters, who were under the control of the clerks or other officers who might have charge of the trade department for the time being, each officer having his special charge, for the good conduct of which he was responsible to the Chief Factor.”

Below is a brief list of just some of the better-known interpreters employed on the Northwest Coast:

| Annance, Francis Noel | (NWC 1820), HBC clerk and interpreter to Columbia with Governor Simpson’s party in 1824; explored Fraser River with James McMillan 1824; Thompson River under McLeod; in charge Okanagan 1825-26; with McDonald at Kamloops 1826-27; helped to establish Fort Langley 1827-28; 1833-34 Mackenzie River (Fort Simpson); to Montreal 1834; returned to his Abenaki village, St. Francis, in 1845. |

| Charpentier, Francis | (HBC 1817), middleman and interpreter Fort Vancouver 1827-28; Walla Walla (Nez Percés) 1829-32; died in Snake country 1834. |

| Gingras, Jean | (NWC 1820) HBC middleman, interpreter Kamloops 1827; settled in Willamette Valley 1841; died 1856. |

| Lafantasie (Lafentasie), Jacques | (NWC 1820, HBC 1821), Fort George 1822; interpreter at Kamloops 1827; died at Thompson River in 1827. |

| Laframboise, Michel | (Pacific Fur Company 1810, NWC 1813, HBC 1821), overseer and interpreter at Fort George from 1822; with A.R. McLeod on Clallam Expedition to avenge the murder of the Alexander McKenzie party in January 1828; settled in Willamette Valley about 1841; died 1865. |

| Leolo (Lolo) | Interpreter and guide, New Caledonia and Thompson River; daughter became fourth wife of Chief Trader John Tod. |

| McKenzie, Patrick | Clerk at Colvile, Flathead House, listed as apprentice postmaster 1841-44, postmaster 1844, interpreter 1851-53; at Thompson River 1844-46. |

| Montignis (Montigny) | (Pacific Fur Company 1810, NWC 1813, HBC 1821), Fort George overseer 1822; middleman, interpreter; 1829 Cowlitz region; Fort Nisqually 1836-42; died c. 1849. |

| Ouvrie, Jean Baptiste | (Pacific Fur Company 1810, NWC 1813, HBC 1821), Fort George overseer 1822; middleman, interpreter; 1829 Cowlitz region; Fort Nisqually 1836-42; died c. 1849. |

| Payette, François | (NWC 1814, HBC 1821), interpreter at Spokane House; Snake Country expeditions with John Work 1830-31; Fort Colvile 1833-35, Flathead and Kootenay posts; at Fort Boise (Idaho)1835-1844 when he retired to Canada. |

| Rivet, François | (NWC 1813 Astoria), came to Pacific coast with Lewis and Clark 1804; HBC Spokane 1822, interpreter; on Snake River expeditions; interpreter at Fort Colvile 1827-37; retired to Willamette Valley, where he died in 1852. |

Within this partial list we find both Francis Noel Annance and Michel Laframboise, members of James McMillan’s 1824 reconnaissance expedition to the Fraser River which led to the establishment of Fort Langley in 1827. The following year Chief Factor John McLoughlin (“The Father of Oregon”) wrote to HBC Governor Simpson stating that he “could sooner dispense with a gentleman than him [Lamframboise]. People only know the value of an interpreter when they have none.” This was certainly the case during John McLeod’s 1824 Nahanni Expedition whereby “the trader’s inability to get sound geographic information [was] for want of an interpreter.”

One of the principal interpreters utilized during the time of the Fort Victoria treaties was an individual referred to as “Thomas.” In a letter written by Joseph McKay to Dr. John S. Helmcken in 1888, McKay – charged with conducting the treaty councils in southern Vancouver Island – makes mention of the Fort interpreter employed during these meetings that produced the Douglas treaties of that region. McKay recalled:

Mr. Douglas was very cautious in all his proceedings. The day before the meeting with the Indians, He sent for me and handed me the [treaty-related] document above referred to telling me to study it carefully and to commit as much of it to memory as possible in order that I might check the Interpreter Thomas should he fail to explain properly to the Indians the substance of Mr. Douglas’ address to them.

If McKay’s words are correct, then it would seem that James Douglas had taken added precautions to ensure that Native representatives assembled at these treaty councils fully understood the meaning of the treaty negotiations. The “Thomas” referred to here is none other than Thomas Quamtany, one of Douglas’ most-favoured interpreters, employed in this role at Fort Victoria through the critical years between 1843 and 1851. Bruce Watson McIntyre’s biographical dictionary of the fur trade states this important linguist “spent the majority of his career at Fort Victoria acting as interpreter. . . Because of Ouamtany’s ability with languages, he was often called upon when a reliable competent interpreter was needed”.

His work with a series of expeditions to explore Vancouver Island lends credence to his facility with languages, having joined not only Adam Horne’s 1856 Expedition (from Qualicum to Alberni), but also Pemberton’s 1857 crossing of the Island from Cowichan to Nitinat, and Robert Brown’s Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864. Captain Sherlock Gooch, who accompanied Pemberton in 1857, stated of the Interpreter that:

By birth an Indian of Lower Canada [Iroquois], he spoke the French dialect of that province well, and also English, and many Indian languages . . . . a valuable addition to any pioneering expedition in North America.

Contrary to Gooch, McIntyre states, from his quite voluminous research, that Thomas Quamtany was not only Iroquois (by his father), but half Chinook, having been born in the Columbia district in what is today Oregon.

At the time of the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864, Robert Brown also gave his testimonial of this Interpreter’s linguistic talents:

He was at one [time] high in favour with Governor Douglas whose constant factotum he was on every expedition. He served for some time in the H B Company in several capacities, as guide, hunter, and interpreter in all of which capacities he stands unrivalled. . . Tomo [Thomas is pronounced Toma or Tomon in French] spoke English without an accent, besides understanding nearly every Indian language on the Island.

These “unrivalled” language skills suggest to me that the Douglas Treaties negotiated in and about Fort Victoria would have been conducted in the languages of the local Indigenous peoples.

Joseph McKay, the principal negotiator of the treaty councils on behalf of Douglas and the HBC, was also known to speak languages other than English, French, and the Chinook Jargon. In 1932, Saanich chiefs presented legal documents to the provincial government stating that they did not recognize the Treaty, had not sold their land, and the agreement was actually a peace-pact. But they also stated they fully understood the treaty negotiations; it had been communicated in their own language such that, “The Indians fully understood what was said as it was interpreted by Mr. McKay, who spoke the Saanich language very well.”

McKay’s response to Helmcken in 1888 that Douglas “was very cautious in all his proceedings” and instructed McKay “to check the Interpreter Thomas,” and perhaps more importantly, “to explain properly to the Indians the substance of Mr. Douglas’ address” are important to reconsider in light of the HBC’s concerted efforts to learn Indigenous languages.

But at the same time one must necessarily ask – “what was lost in translation?”

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's last piece was a look back at a titan of BC history - Margaret Ormsby.

- Daniel also touches on his work with the Cowichan Tribes on the return of Chief Tsulpi’multw’s ceremonial blanket.

- Bob Price on an industry rapidly becoming history in the Interior - horse racing.