Over the years I’ve had more than a few occasions to travel from British Columbia down the I-5 Highway to California, and there is one small town that always captures my interest – just by mere mention of its name.

“Dunsmuir, California you say?”

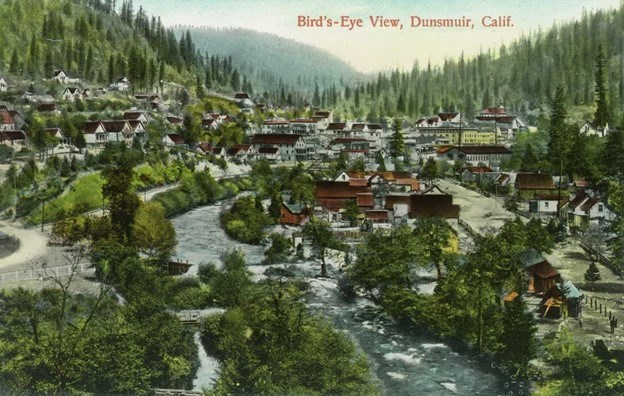

My fellow traveler, a British Columbian who had recently moved to San Jose, raced by the historic railway town that clings to a mountainous edge along the upper Sacramento River, with Mount Shasta looming above. I wanted to stop, but admittedly it can be rather tiresome driving with an historian who demands to halt at each and every corner of historical significance!

“We don’t have time – we have to reach the BC border tonight,” he snapped.

I was a bit peeved, though his reaction was understandable, having already detoured through many small-town wonders of California’s northern gold fields.

But Dunsmuir! From that point on I was determined to see this intriguingly named town for myself, subsequently having the pleasure of staying twice in future years.

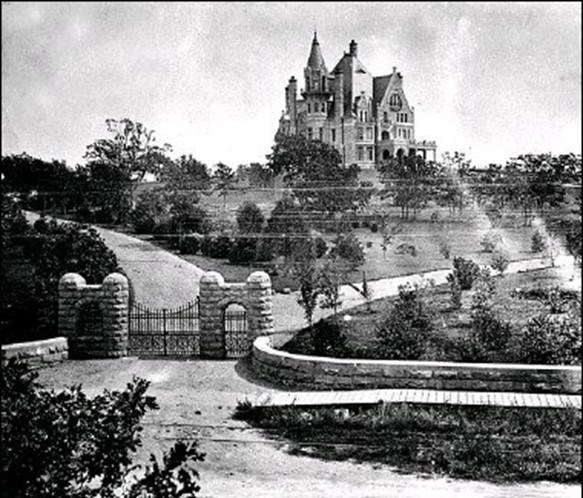

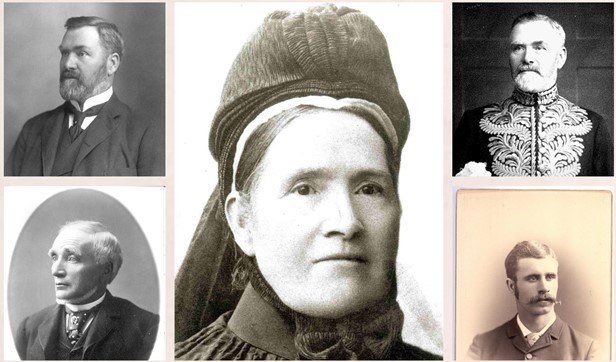

Who has not heard of the wealthy Dunsmuir family of British Columbia? Surely one of the greatest rags-to-riches stories found along the northern Pacific Slope. Coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, initially in the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company, became famous (some say infamous) for the development of the Nanaimo coal mines, building the historic Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway, and particularly for erecting a promised home to his wife Joan – today’s magnificent Craigdarroch Castle in Victoria.

While California had the Bonanza Kings whose fortunes were built on the wealth of Nevada’s celebrated Comstock Lode, Robert Dunsmuir was the Northwest Coast’s “Coal King.” In fact, when Dunsmuir visited San Francisco’s “Big Four” (wealthy businessmen Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker) they became the “Big Five,” as reported in the press of the time. In short, he accumulated immense wealth from selling high-grade Vancouver Island coal that fueled the Big Four’s extensive railway operations, particularly the Central Pacific Railway.

But why was this Californian town called Dunsmuir? Having taken a room at a cozy, converted railway caboose, I set out the next day for a bit of exploring, wandering the streets and outskirts of a locale once called Upper Soda Springs. It was a Hudson’s Bay Company camp stop on the trail system that once extended from BC to their post in Yerba Buena (San Francisco). By the time of the railway, it became known as Pusher, a name that described the need for additional locomotive force to literally push trains up the steep rail bed.

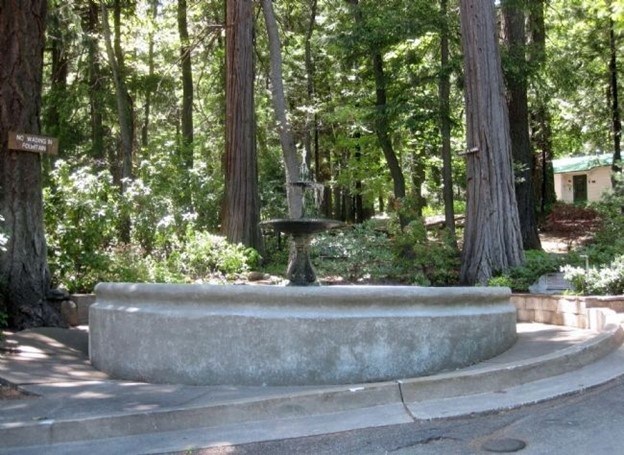

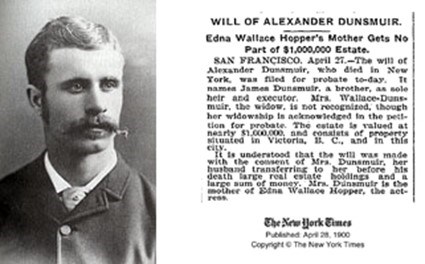

One day Robert Dunsmuir’s son, Alexander Dunsmuir (1853-1900), came whistling into town, marveling in the scenic beauty and pristine waters. It was then that he apparently offered to build them a fountain if the community officially changed its name to Dunsmuir.

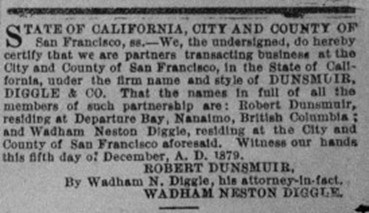

While British Columbia history has tended to focus more on his father (who had inaugurated harsh labour practices in the coal fields of Nanaimo), or his older brother James, the province’s 14th premier and later lieutenant-governor, it was Alexander who was placed in charge of the family’s business operations in San Francisco, becoming a well-known bon vivant in the social and cultural circles of the golden state.

Here again is the California-British Columbia connection that so dominated Pacific Slope communities in past times. As the provincial archivist Willard Ireland once wrote,

“A century ago Victoria and San Francisco were close neighbors, so to speak. There was no Vancouver; Seattle and Portland were hardly worth mentioning. British Columbia’s first business firms were branches of San Francisco firms. In Victoria were the ‘What Cheer House’ and ‘The San Francisco Baths’ and a branch of Wells Fargo” among many others. Victoria, asserted Ireland, “to the horror of those who like to fool tourists, is not, and never was, a bit of old England but a bit of old San Francisco.”

While the “Lady of the Fountain” is but one, admittedly obscure, legacy of Alexander Dunsmuir’s time in California – including the mountain town’s new name – there is also a much greater monument to his fateful life in San Leandro, the Dunsmuir Historic Estate built in 1899.

Alexander had been in charge of the family’s business operations in San Francisco since 1878. Out of the watchful eye of his mother Joan Dunsmuir, Alexander commenced an affair with his favourite bartender’s wife, Josephine Wallace. The two subsequently lived together for many years, along with Josephine’s two children, William Wallace and Edna Wallace Hopper, who later became a well-known actress, but the couple did not marry until 1899.

The wedding was delayed until their father’s death, as Alexander and his older brother James finally took control of the family business – and therefore were now free of their mother’s “disapproving eye and financial control.”

Until this time, Alexander had not only been “living in sin,” but the secretive life he had adopted apparently had also encouraged companionship with the whiskey bottle, and he became an incurable alcoholic. The immense wealth of the Dunsmuirs could not save him, as “his whiskey habits got the better of him and he died during their honeymoon to New York in January, 1900.”

Alexander and Josephine selected New York for the honeymoon as it coincided with his celebrated stepdaughter’s performance on the New York stage. Just like his father Robert before him, Alexander promised his newlywed wife a mansion, and construction was completed during their absence. Once they returned to California, the plan was that Alexander would cross the marital threshold with his new wife into the Greek-revival mansion – but with his death in New York, Josephine was left to return to the new home on her own.

Just imagine waiting over 20 years to get married, then traveling back across the continent to a grand mansion that had been promised you – empty.

While the vast majority of Alexander’s estate was willed to his brother, now the Premier of British Columbia, Josephine’s occupation of the California mansion came to a quick end, just a little over a year later in 1901, when she followed her husband to the grave.

Enter the Flapper and the Premier, the BC court case that scandalized the public.

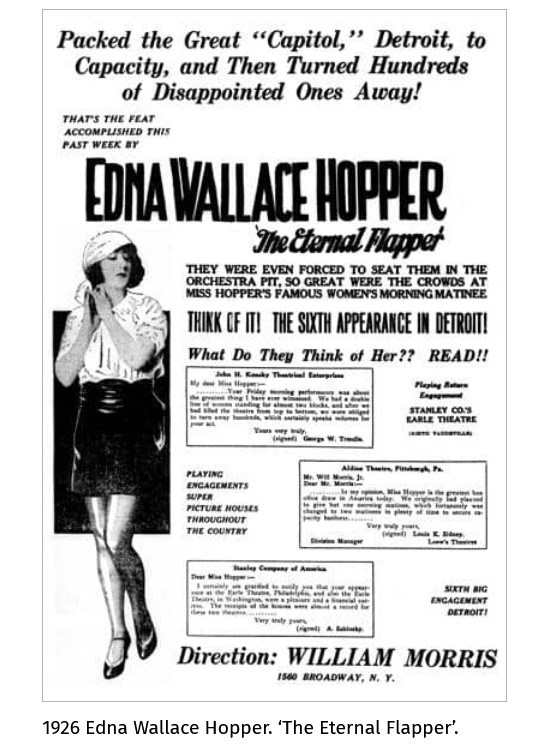

Alexander Dunsmuir’s famous step-daughter, Edna Wallace Hopper (1872 – 1959), was an American actress on stage and in silent films was known popularly as the "Eternal Flapper." She soon inherited the San Leandro home from her deceased mother’s estate. In short order, not satisfied with inheriting the family home, Hopper began legal proceedings in both California and British Columbia against Premier James Dunsmuir.

Accusations were leveled that the premier had used his influence on behalf of the Dunsmuir family with the ailing widow Josephine to deny her any rights to the larger Dunsmuir fortune following her husband’s untimely death, beyond that of the mansion and a payment of $25,000 (possibly an annual annuity) that was ultimately accepted.

Edna Wallace Hopper was of the belief that the premier had used undue influence, and denied the mother her rightful share, especially as she had endured a secretive relationship with Alexander for over 20 years. The Eternal Flapper had known the hardships of living with an alcoholic stepfather – after all, she had lived with him and her mother during her younger childhood.

James Dunsmuir entered the BC legislature in 1898 and became the 14th Premier in 1900 – though soon resigned in 1902, apparently disliking politics. One wonders whether his departure was influenced by the dramatic court cases brought against him during his premiership. One of the most important and influential families in BC history, the Dunsmuirs were not immune to scandal. In the early 1900s, big crowds followed the court cases initiated by Edna Hopper that involved alcohol abuse, inappropriate behaviour, and a Broadway star looking for a piece of the Dunsmuir fortune.

Reported in the San Francisco Call, 21 January 1902, under the headline “Actress Seeks New Settlement” it was reported that “Edna Wallace Hopper, the actress . . . is about to enter suit at Vancouver, B.C., against James Dunsmuir, Premier of British Columbia and brother of her late stepfather, Alexander Dunsmuir, to set aside her stepfather’s will.” The report continued:

If she succeeds in setting aside the will she will get all of her mother’s interest in the estate, which under the laws of California amounts to one-half. In this case the estate is variously estimated to be worth from $1,000,000 to $3,000,000. It comprises coal fields of Vancouver Island and a large share of ownership of the Vancouver [Island] Railway. Mrs. Hopper will ask for the setting aside of the will on the ground that James Dunsmuir, the Premier, used undue influence on Alexander Dunsmuir to procure the making of a will unfair to Mrs. Dunsmuir and her heirs, and he unfairly influenced Mrs. Dunsmuir to waive her rights to contest the will . . . it is alleged that Alexander Dunsmuir was suffering from cerebral meningitis when he signed the will in his brother’s favor, and that he died thirty minutes afterwards. Mrs. Hopper also says her mother, Mrs. Dunsmuir, came under the influence of James Dunsmuir at a time when she was hovering between life and death late in 1899, and accepted $25,000 in lieu of her rights to contest.

The case not only titillated British Columbians, but increasingly scandalized the Dunsmuirs as court actions dragged on for four years. Witnesses were called throughout, testifying either for or against the state of Alexander Dunsmuir’s mental capacity. The case was considered one of the most complicated and expensive in the annals of British Columbia history. Even Joan Dunsmuir, Alexander’s mother, contested the will!

Litigation had apparently involved five separate actions, appeals, and cross actions in the BC Courts. At the trial’s end in 1906, the Privy Council in London, England – then Canada’s highest court of appeal – decided in favour of James Dunsmuir and against both Edna Hopper and Joan Dunsmuir. With the closure of the dramatic trial, the Premier, following the example of both his father and younger brother, used the windfall to build his own mansion, that of Hatley Castle – which still stands, part of Royal Roads University.

Today, Alexander Dunsmuir’s “Lady of the Fountain” is located in a remote and somewhat forgotten corner of California, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the town attracted many visitors, like Alexander, to the pristine waters and soda springs for their reputed health restoring properties.

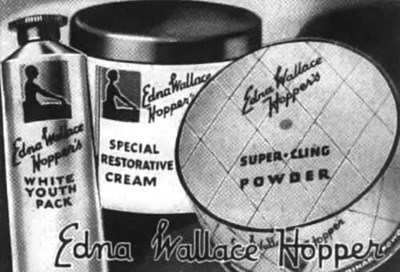

Indeed, the Dunsmuir fountain poured “the best waters on earth” (the official city slogan) – a veritable fountain of youth. And so, it is fascinating that his stepdaughter, increasingly known as the Eternal Flapper, would later build on the success of her acting career to lend her name to a range of age-defying cosmetics. Hopper never did reveal her true age, always maintaining that her birth record was destroyed in the great San Francisco fire of 1906.

The local historian and journalist James K. Nesbitt (1908-1981) wrote, 19 November 1972, that “the darling of Broadway” actually traveled to Victoria twice: first for the court case, but once again in the 1920s when “she came here billed as ‘the eternal flapper,’ and took a bath on the stage of the Royal Victoria Theater, a performance for ladies only, with extraordinary precautions to keep away all Peeping Toms.”

While Dunsmuir’s fountain was something of a conceit of a man doomed to die at an early age, his stepdaughter, Edna Wallace Hopper – though defeated by the premier – would ride her own Fountain of Youth to further fame and fortune.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).