Remembrance Day always brings family stories to the fore.

Imagine what life must have been like on southern Vancouver Island in 1893, the year my great uncle was born. British Columbia had only been in existence for 35 years since our family’s arrival during the tumultuous days of the Fraser River gold rush, and BC a part of Canada for only a little over two decades.

One of the eldest of five children (my grandfather being one of the youngest), Uncle Ernie was born into the wild, rural landscape of Saanich just beyond the capital, then a land of splendour largely untamed and dotted with tranquil farms and expansive hunting grounds.

Ernie knew much about pioneering life: his father had been Judge Peter O’Reilly’s “factotum” at Point Ellice house where his parents first met. Ernie spent a pretty much carefree youth wandering the lands fishing and hunting, soon to become a crack shot with the rifle. Vancouver Island was full of this sort of young men who, when war was declared, soon signed up for overseas duty in “the war to end all wars,” the Great War of 1914-18.

“I forbid you to go!” implored my great grandmother Mary, also having beseeched Ernie’s older brother, my great uncle Rupert who also intended to go. But all her ardent attempts had failed; the two young lads – now in their early 20s – had taken up the fervent call to arms. No wonder: the celebrated General Arthur Currie (first Canadian commander of the Canadian corps), who would later command the troops in France, was a well-known Victorian who actively supported the large-scale recruitment of local men and the formation of the 88th Battalion as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force to Europe.

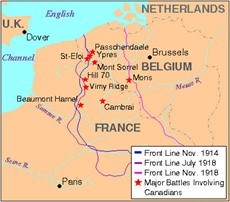

It was Currie’s military genius (not without controversy) that would put Canada on the map, and, in many ways, it was Currie’s influence both at home and abroad that ultimately placed my great uncle into a terror-filled, front-line trench in France during the Battle for Hill 70 in the month of August 1917.

My grandfather Art reflected years ago that his older brother, swept up with the patriotic fervour of the moment, was indeed “one of General Currie’s Boys!”

The day Ernie departed from the docks of Victoria’s Inner Harbour, 23 May 1916, aboard the S. S. Princess Charlotte, the Daily Colonist wrote the immense sendoff was “one of the most inspiring that has been seen here since the beginning of the war.” Ernie had enlisted in the 88th (Victoria Fusiliers) Battalion of over one thousand men.

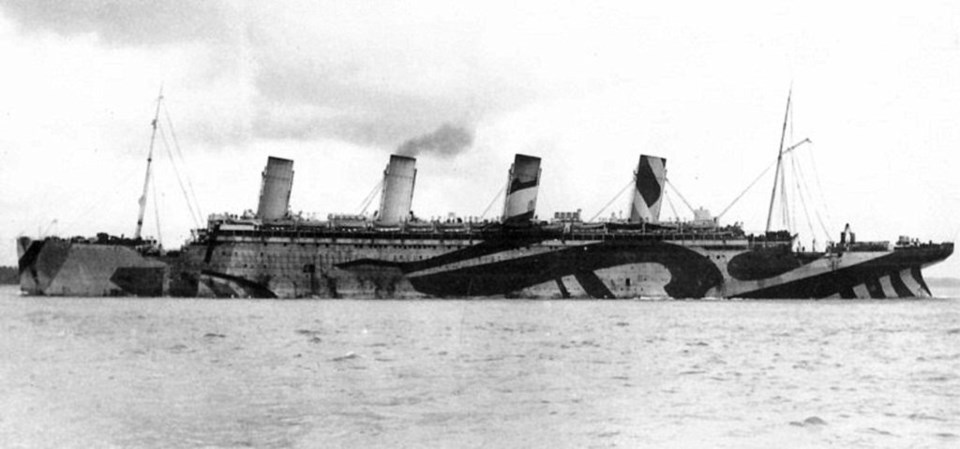

From Vancouver, these fresh troops were whistled across the continent by rail to Halifax before next departing on the RMS Olympic, an immense luxury-liner and sister ship to the infamous Titanic, converted into a troop carrier.

For a 23-year old Island boy like Ernie, this was about as far away as he’d ever been – and yet the overseas expedition had barely begun. His tranquil farmlands would be a memory shortly eclipsed by the horror of war.

Disembarking in England, 8 June 1916, Ernie was first transferred to the 3rd Canadian Pioneer Battalion, then shipped out to France and reassigned to the 7th Battalion (1st British Columbia) of the Canadian Expeditionary Force destined for the frontline trenches of Hill 70 in Lens, France, a coal mining town that had been occupied by German forces in 1914. The better-known Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 1917) fought so valiantly by Canadian troops had concluded some four months earlier; but unlike Vimy the Battle for Hill 70 was the first time that a Canadian was put fully in command, Victoria’s own General Currie.

There may have been some small comfort knowing one of the Island’s own was in charge, once in the trenches the grim reality of war was faced head on with German snipers and heavy artillery just a short distance across a foreboding “No Man’s Land.”

While British generals advocated a direct attack on Lens, Currie successfully argued they should first take the high ground of Hill 70 (so named because it was 70 meters above sea level).

During these strategic deliberations, my grandfather recalled a poignant story shared with him in later years by his brother. One day while squatting down in a deep trench at the Western Front, Ernie received a letter from his mother. Inside, my great-grandmother had included some much-needed tea – the very foundation of existence in our family!

These men were not among the American latecomers (“the Rainbow boys” as one Vimy Ridge vet informed me years ago) that were apparently being supplied ice cream and other luxuries. Simple pleasures were far and few.

Ernie and his comrades set to building a campfire in the bottom of the trench – a “billycan” placed atop the flames to boil water and steep the tea. “What a treat this would be,” my grandfather remembered him saying. But it was too hot for immediate consumption, and so they foolishly placed the impromptu pot atop the trench to cool…only to have a German sniper shoot the can to oblivion. So much for tea time! It was a great disappointment, their anticipation of a simple respite gone in a flash.

Finally, the fateful day arrived, 15 August 1917. Currie’s surprise plan of attack was finally launched at 4:25 AM “under a creeping barrage and smoke screen.”

From the book Letters of a Canadian Stretcher-Bearer:

At 4:20 am you’d have thought the earth had cracked open. My God, it was marvelous! I don’t know how many guns we have, some say one to every three men… With the first roar we manned the trench and began to move… No power on Earth could keep us from getting on the parapet to have a look. It was too dark to see the men advancing behind the barrage, but the line of fire – ye Gods! Try to imagine a long huge gas main which had been powdered here and there with holes and set fire to. The flame of each shell burst and merged into the flame of the other. It was perfect. It was terrible. The flames were dotted with black specks which were bits of rock and mud… After some while, the barrage died down. Only the scream of the heavies overhead and the whirr of planes and the heavy crump, crump, crump of Fritzie’s shells behind us searching for batteries. He might as well have tried to shove the sea back with a broom.

Unfortunately for Ernie, during the mayhem of the very first day, he was wounded, hit in both legs at the knees with flying shrapnel, and recorded in his military medical records as “G.S.W.” or gun shot wounds.

In our family’s oral history, Ernie pleaded with his trenchmates to get the hell out of the trench and head for the backline, but they were all too panicked and frightened to follow. He reluctantly left them behind, never to see them again. In epic fashion, Ernie proceeded to drag himself hand-over-hand across the battlefield, his legs having become of little to no use, until finally he reached help.

Just imagine the intensity of the smoke and fire, snipers and howitzers ablaze, the bombardment from the air – all experienced by a young farm lad in his early 20s, desperately dragging himself through hell on earth.

If that was not already enough, German gas attacks commenced three days later on 18 August, and Canadian soldiers were exposed to mustard gas which burned the skin and caused blindness. (Both German & Canadian forces used such poison.)

While Hill 70 was taken successfully, the casualties for the first six days of battle were incredible: 5,600 wounded, killed, or missing.

Ernie was one of the wounded, but lucky for him was shipped back to England, the shrapnel removed from his legs, and convalesced in a number of hospitals for the next six months. From his “Medical History of an Invalid” dated 8 August 1919 we learn that “once in a while when walking a long distance (8 miles) [Ernie] gets sharp pains in knee joints, painful to bend on knee.” Nevertheless, Captain Blackadder, the medical officer in charge, certified that he was “Likely to be raised within six months” for further active duty.

While six Canadians received the Victoria Cross for their actions of valour during the Hill 70 battle, for my great uncle there remained the stark memory of leaving his companions behind, and just barely escaping death. In our family lore, after Ernie had made an almost complete physical recovery from his injuries, he was considered for further frontline duty – until his brother Rupert, who worked as a blacksmith in England for the war effort, convinced military authorities not to send him back.

Can you imagine the prospect of being sent back!

Ernie remained in England for the remainder of the war, but a young man who had suffered the severe shock and awe of gruesome conflict, or what we today would recognize as profound post traumatic stress disorder. It was something he contended with for the rest of his life.

Once the cheery and innocent farm lad, Ernie suffered the consequences of war and his frequent depression finally got the best of him.

I remember a fateful Christmas Day when I was still quite young when we kids were excitedly awaiting our trip to my grandparents’ house for our celebratory dinner. That is, until my mother received an urgent telephone call from her father – it was announced then that Christmas was cancelled.

On Christmas Day 1972, my grandfather found his brother dead. Ernie took his own life, having turned his own gun upon himself – the remembrance of the so-called Great War undoubtedly haunting him to his grave. How terribly tragic indeed.

Is my ancestor’s story unique? Unfortunately not. Look at any number of cenotaphs in British Columbia that mark the memory of a lost generation of young sons (and fathers) who gave their lives in the tragic battles of the First World War.

Unlike Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, the Battle of Hill 70 was largely forgotten for about 100 years. But this Remembrance Day – indeed every Remembrance Day – our family will never forget Uncle Ernie or the incredible sacrifice he and so many thousands of others like him made in “the war to end all wars.”

This Remembrance Day, have a look at one of the many cenotaphs found throughout this province, think of the incredible hardships endured by these brave souls, and, more importantly – never forget. Ernie is commemorated on the Municipality of Saanich’s WWI Honour Roll. May our ancestors Rest in Peace.

For those wishing to view their own ancestors’ war records, see this Government of Canada searchable database.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Back in March, Daniel Marshall concluded the second part of his in-depth look at the pandemic of 1919, and the lessons for today.

- Daniel was one of The Orca's original contributors, and we're delighted to have him back. His very first piece in October 2018 looked at the legacy of "British California."

- Last August, Daniel told a ripping good yarn about hiking the "graveyard of the Pacific."