I remember well the time when my father and I traveled to Bamfield on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

I was about 11 years old, and the purpose of our journey was to deliver my brother and cousin to the top end of the West Coast Trail, which they had been planning to hike. We joined them for the first leg of the excursion and camped for the night just before the Pachena Lighthouse.

What a night it was! The weather had begun to turn, hundreds of seagulls landing on the shoreline below (an indicator of what was to come). My father quickly constructed a lean-to shelter against a high rock cliff that overlooked the wide expanse of the ocean below.

That night, laying under a makeshift enclosure and lying on a bed of freshly-cut bracken ferns, the heavens opened up in a massive deluge of rain, the wind roaring the whole of the evening, my father periodically lighting a candle (we had no flashlight) to check the time.

It was an exciting night indeed, and I remember turning my head towards the coastline below, the mighty Pachena Lighthouse station blowing its horn and casting its brilliant, circulating beam of light across the wave-crested waters to warn ships of the perilous reefs beneath us. “Wow Dad, is that a ship I see below us?” Indeed it was, hugged to the coast directly below us to escape this sudden and fearful storm.

This was my first experience on the Graveyard of the Pacific.

Through the long night of fitful sleep, my father began to share the stories of his own expedition many years earlier on what had become known as the West Coast Trail (and long before it became a National Park).

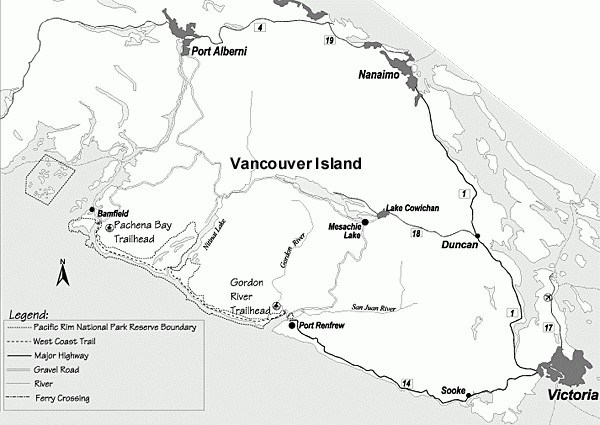

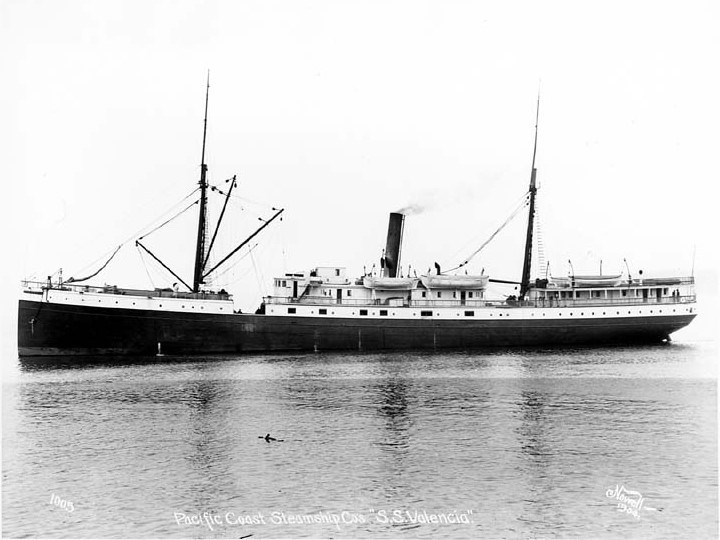

The Graveyard of the Pacific earned its name from the hundreds of ships that met a watery grave – stretching from around Tillamook Bay on the Oregon Coast all the way up to Cape Scott on the northern tip of Vancouver Island. On the south and west sides of the Island alone, there have been close to some 500 wrecks since the early days of European exploration, but it was one in particular – the ocean liner S.S. Valencia of 1906 – that saw 100 lives lost and was the impetus for building the Dominion Lifesaving Trail the following year.

That trail became today’s West Coast Trail. The wreck of the Valencia is considered by some to have been the worst maritime disaster in the Graveyard of the Pacific.

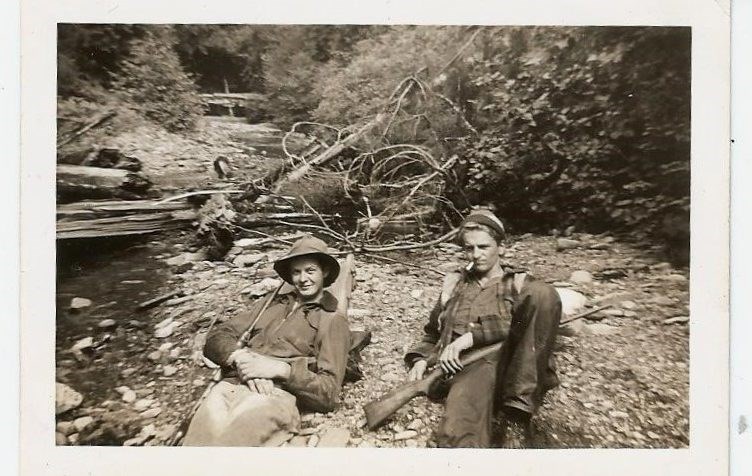

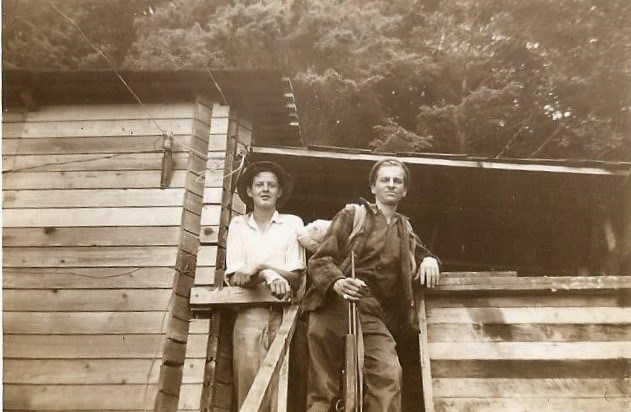

In 1953 my father Tom, along with his two chums John Mugford and Fred Vosper (later captain of the legendary tugboat, the Nitinat Chief), were dropped off from Victoria about 8 kilometers past the community of Jordan River where they began their search for the beginning of the old lifesaving trail – it extended that far south in those days.

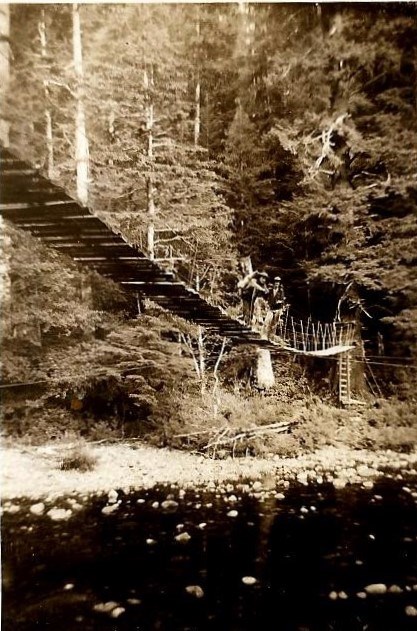

"Their first test was to transport themselves across the canyon using an old cable car, hundreds of feet in the air, with the original floor boards rotted away."

They had a heck of a time finding it, toiling around the impenetrable bush of high, dense salal the entire day. This portion of the 1907 lifesaving trail was later developed as the Strait of Juan de Fuca Trail, a separate section not included in the Pacific Rim National Park created in 1973 that encompasses the West Coast Trail.

By 1953, the trail had become overgrown and infrequently traveled. Reaching Loss Creek (near Sombrio Beach) their first test of endurance was to transport themselves across the canyon using an old cable car strung hundreds of feet in the air, a steel cage with the original floor boards rotted away.

The salal was so thick and overgrown at the approach that they had no idea of the height they were about to cross, but a previous traveller had tacked the remnants of a cigarette package onto the side of it with the reassuring words penned that a “safe crossing made by a man and his dog” had been accomplished some six months earlier.

It was decided that Mugford, as the smallest of the three, should be the first to try the rusting, dilapidated conveyance. Sitting on the edge of the steel cart, Mugford quickly rolled out into the middle of the Canyon – his first view of the incredible height he found himself led to the excited yell, “Get pulling that damn rope quick!” Each held their breath and made a safe crossing.

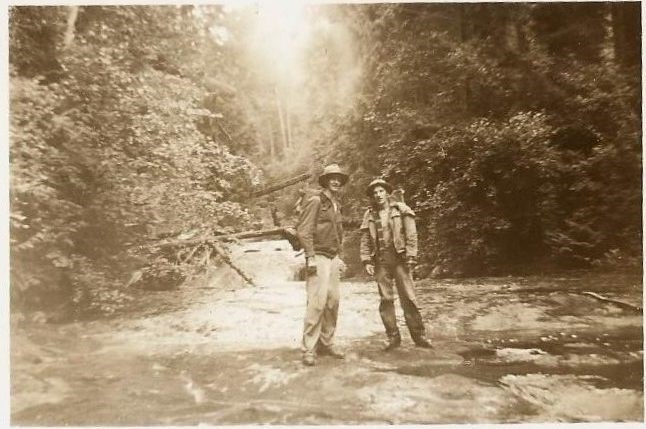

As they continued their journey, this trio of young adventurers found the terrain tough and challenging, with many of the old growth trees cast down by winter storms used as impromptu footpaths above the dense underbrush that was reclaiming the original 1907 trail, and oftentimes these friends beat a retreat to the sandy foreshores for an easier transit. Imagine what it must have been like for shipwreck survivors in previous times, this trail being their only means of escape and passing through the traditional territories of the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples (Pacheedaht, Ditidaht & Huu-ay-aht) who have lived along the coast for thousands of years.

Non-Indigenous use of the trail first started with the building of a telegraph line that ran from Cape Beale all the way to Victoria.

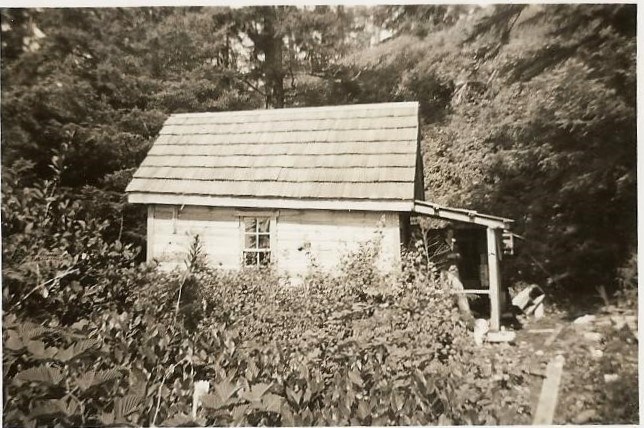

Shelters for the use of linesmen and shipwreck survivors were also constructed at 8 kilometer intervals on the trail, each with a telegraph with instructions in a variety of languages, survival provisions, blankets and rations. My father and his friends made use of these small cabins throughout their two-week journey towards Bamfield.

"What the hell you boys doing out here?"

Along the way, they fished and did a little hunting with my father’s 22-caliber rifle to augment their limited food supplies. All went well and they finally reached Port Renfrew as the first leg of their journey. At one point they encountered a linesman who heard them coming in the distance. Thinking it must be a bear approaching, he had his shotgun ready and leveled right at their heads. “What the hell you boys doing out here,” he exclaimed!

This was not the hiking trail of modern times. He was rather shocked to see anyone that far out into the bush. After some conversation he invited them to make full use of the cabin-shelters.

At one of these huts, my father decided to give the old telegraph system a try, cranking up the telephone to call his mother back in Victoria. “Where are you son?” she asked and relieved to hear from him. “I’m at Camper Bay!”

She had no idea where that was exactly, but glad to know he was alive and well.

The hearty trio continued their journey. While they had managed to supplement their limited stores with the occasional fish or duck, by the time they reached the Native village of Clo-oose their food supplies were running a bit thin. Hiking into this legendary village along an elevated boardwalk they were made welcome, and purchased cans of beans and other essentials from the local Native-run store.

Other than the linesman, these were the first people they had seen; nobody was hiking the trail at this time – certainly not young tourists like my father and his friends.

With their food supplies replenished, the Carmanah Lighthouse became their next destination. The trail though this section was apparently in better shape. Suspension bridges now met their eyes for which they were glad to walk on.

At Nitinat Narrows two Native teenagers obliged them and ferried them across the river in a large canoe in exchanged for half a case of 22 caliber shells – they were delighted. Continuing to make use of the lifesaving shelters found every 8 kilometers they eventually wound their way to the Carmanah Lighthouse.

As before, the lighthouse keeper (possibly G. D. Wellard, 1952-58) was astounded to see these three young lads drift in:

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

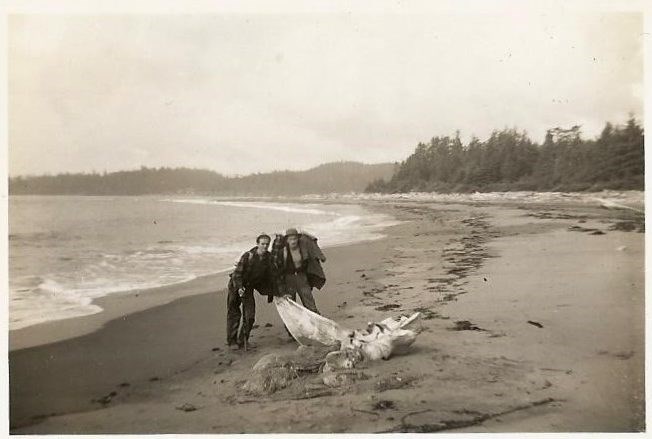

Imagine a time when lighthouse keepers were so happy to see another soul, certainly not like today now that the trail has become so inundated with modern tourist-hikers (where reservations are required and limited to about 10,000 people per season). Marshall, Mugford and Vosper were made so welcome that they stayed as guests at the Carmanah Lighthouse for two nights, were fed and provided lodgings with plenty of time to explore that part of the coast and seeing evidence of at least three past shipwrecks.

In fact, my father was given the task the first evening of cranking up the mechanical mechanism that powered the movement of the old light, and using a striker, lit the kerosene that provided the big-beamed torch that swept the evening sky.

From Carmanah the lads continued their journey toward Bamfield, stopping in at Pachena where they were also welcomed by the lighthouse keeper there. No tents or upscale camping gear accompanied this trip – so unlike today – but then modern hikers do not have the luxury of stocked cabins strategically placed at defined intervals!

"They were a harbinger of the immense crowds of enthusiastic hikers who would follow in later years."

When the threesome finally arrived in Bamfield the employees at the historic Cable Station (the terminus of a 7,000 mile long cable between Bamfield and Australia) were just as surprised as all the other folks they had encountered along the way, that three 20-year olds had walked the entirety of the original 1907 Dominion Lifesaving Trail, and not for the purposes of being rescued, but recreation. In that way, they were a harbinger of the immense crowds of enthusiastic hikers who would follow in later years.

Nevertheless, Marshall, Mugford and Vosper had completed their journey, and perhaps as recognition of their youthful determination and accomplishment were treated to lunch in the big dining hall of the Marine cable station. This was, indeed, Old Vancouver Island.

It’s incredible to think just how much has changed even during my own lifetime, let alone my father’s. The West Coast Trail today is considered one of the top hiking trails in the world.

“Do you want to hike it again?” I asked my 86-year old father last week.

“Yes” came the instantaneous reply, “but while the spirit is willing – the flesh is weak.”

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

SWIM ON:

- Mike Robinson explored the west coast (best coast) a very different way - by kayak.

- Doug Firby found an even more modern way to discover paradise BC style, taking his motorcycle to the Kootenays.

- This isn't the first time Daniel Marshall shared his deep family connection to BC and Vancouver Island. Here, he recounts tales from his grandfather.