Editor’s note – This is Part 2 of Daniel Marshall’s series looking at the last pandemic 100 years ago. Read Part 1 here.

Health authorities in countries around the world are continuing to grapple with a tsunami-like virus and the very real dilemma before them – the goal of securing public health that, at times, is seemingly in competition with the health of imperiled economies.

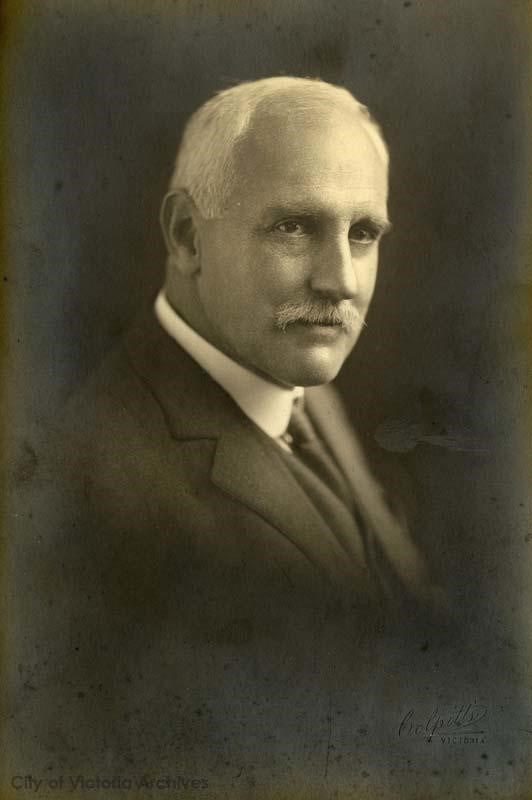

In my previous article I told the story of a far-sighted medical officer in the City of Victoria. Over 100 years ago, he became one of the great unsung heroes in British Columbia history, asserting immediate prevention programs and public closures during the Influenza crisis of 1918.

During that now largely-forgotten crisis, Victoria fared much better than Vancouver, where similar closures were delayed for the greater part of the critical month of October 1918. What further lessons from the past might we learn about the extraordinary measures then taken, and how are they applicable today?

It seems to me we are experiencing a delicate dance between two competing goals: maintaining the health of interdependent economies; and literal public health. This balancing act informs the global medical debate: a reactive wait-and-see stance versus proactive mandatory measures, like those considered by Washington State Governor Jay Inslee now that Seattle is an epicenter of Coronavirus.

Inslee has an historic precedent to follow: Washington State decreed mandatory public closure over 100 years ago in response to the 1918 Influenza pandemic – about the same time as neighbouring Victoria.

In a Seattle Star article, 7 October 1918, it was reported how our neighbours to the south had taken quick, decisive proactive measures:

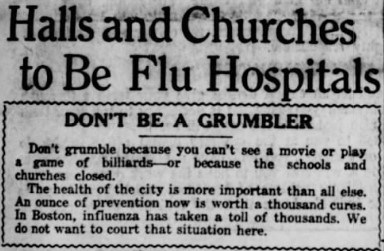

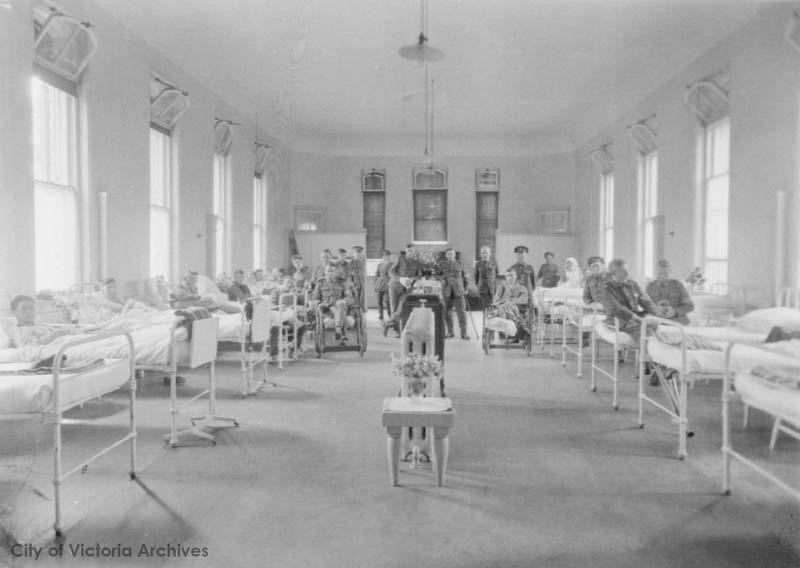

Preparations were under way Monday by Mayor [Ole] Hanson and municipal health authorities to transform Seattle’s big public dance halls, and churches if necessary, into emergency hospitals to care for Spanish influenza cases if the epidemic is not checked. This action was decided upon as a preparatory measure, supplementing the order of Saturday that closed schools, theatres, motion picture houses, pool halls, and all indoor assemblages. . .’ I have the police to enforce the order, and intend to see that it is observed. The health department is doing everything possible to prevent the spread of the epidemic.’

“Of course we will have kickers,” declared Hanson, “but we would rather have live kickers than have to bury them.” The mayor’s declaration was swift. When a Seattle pool hall refused to obey closure orders “police locks were placed on the doors.”

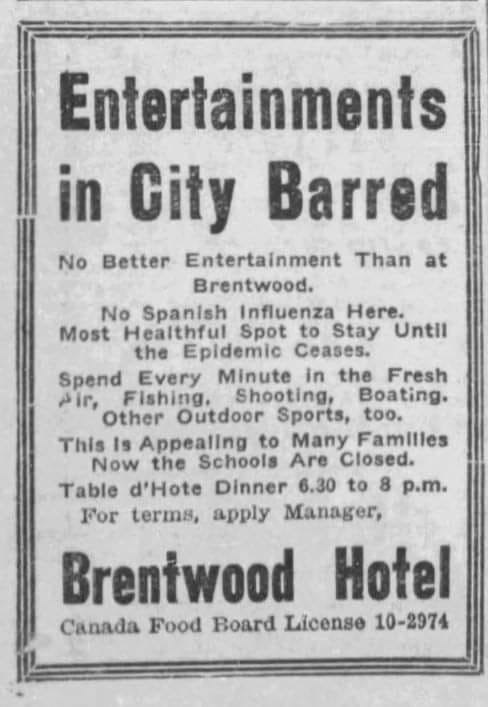

In 1918 Victoria’s medical health officer, Dr. Arthur Price, also took decisive measures, placing a ban on public gatherings that lasted for 33 days, and with seemingly good results. The lower mortality rate of 3.6% compared stunningly with the foot-dragging that contributed to Vancouver’s much higher rate of 10%. Vancouver had stubbornly refused to follow Victoria and Seattle’s example. Price’s mandatory measures were subsequently not limited to the Capital Regional District.

By mid-October 1918 some 16 municipalities in BC had implemented similar bans on public gatherings. A general fear began to grow that if Vancouver did not follow suit, the virus would spread to these closed towns. With increasing public pressure Premier John Oliver’s provincial government began to push Vancouver to get in line – and an impatient Victoria went so far as to ask the BC government to institute a quarantine against Vancouver!

Part of the problem stemmed from disagreement between two schools of medical thought on how exactly to grapple with the highly contagious 1918 influenza. Many felt that the City of Vancouver was misguided; as the largest population centre in the province it should ban public assemblies. The Province, at first reluctant to issue stern threats, nevertheless made it abundantly clear that if the pandemic didn’t subside soon, they would intervene with a mandatory closure order – and so they did.

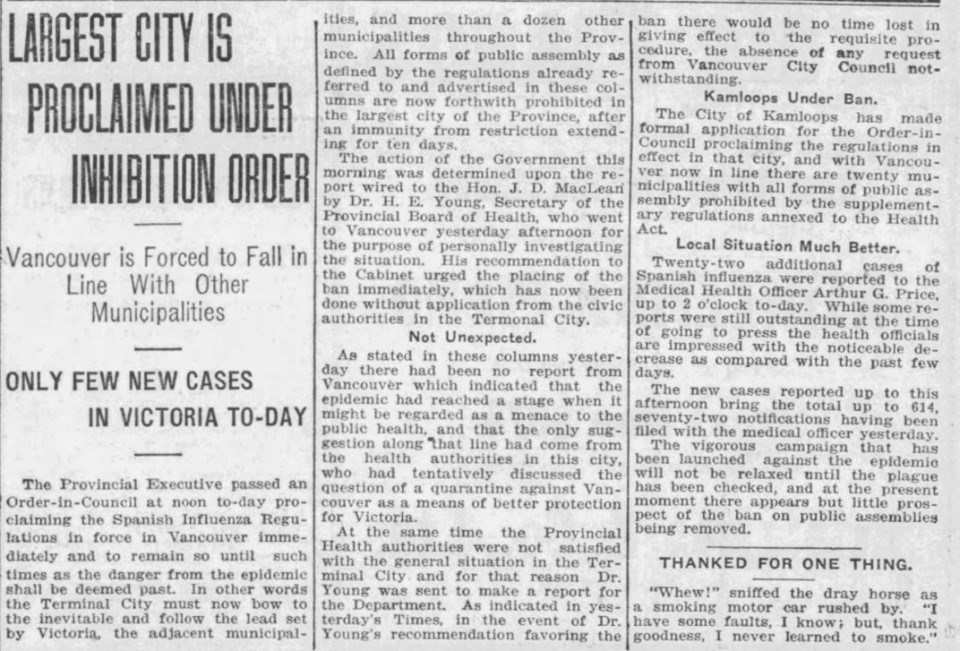

In a Victoria Daily Times article, 18 October 1918, entitled “Largest City is proclaimed under Inhibition Order” the provincial government moved swiftly to make Vancouver comply:

The Provincial Executive passed an Order-in-Council at noon to-day proclaiming the Spanish Influenza Regulations in force in Vancouver immediately and to remain so until such times as the danger from the epidemic shall be deemed past. In other words the Terminal City must now bow to the inevitable and follow the lead set by Victoria, the adjacent municipalities, and more than a dozen other municipalities throughout the province. All forms of public assembly as defined by the regulations. . . . are now forthwith prohibited in the largest city of the Province, after an immunity from restriction extending for ten days . . . . [and] done without application from the civic authorities in the Terminal City.

Vancouver had been forced to get in line with Victoria and Seattle. “The chief of police has been given orders. Dances halls were ordered closed last night. No private dances must be held. Persons spitting on sidewalks or in street cars are to be immediately placed under arrest.” Police officers served notice to close all theatres, movie houses, and other places of public assembly.

Clearly, the institution of closure powers in the transnational triangle of Victoria, Seattle and Vancouver (belated as it was), would be more effective if each city, with their historic connections, worked in concert. And in this instance, securing public health was done so even at the risk of imperilling these regional economies.

So, will public health be trumped by economic health? Our respective governments will let us know in due course.

British Columbia Pandemic Provincial Coordination Plan (revised 5 March 2020)

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Part 1 of Daniel Marshall's look at the "Spanish Flu" pandemic of 1918-20.

- Jody Vance and George Affleck broke down all the latest COVID-19 developments in UnSpun 62.

- Time for something lighter, yes? In November 2018, Mike McDonald revealed the awful truth: he had been a teenage vote-splitter.