Ancient artifacts have always held my fascination, especially those accompanied with curious stories that have been seemingly lost to time. Ever since the Spanish first explored the Northwest Coast, Indigenous artifacts were either gifted or traded with Europeans – and in far too many instances simply stolen. And these antiquities can be found throughout museum collections both locally and around the world.

In particular, the centuries-old argillite carvings of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlottes), such as those produced by the legendary artist Charles Edenshaw (1839-1920).

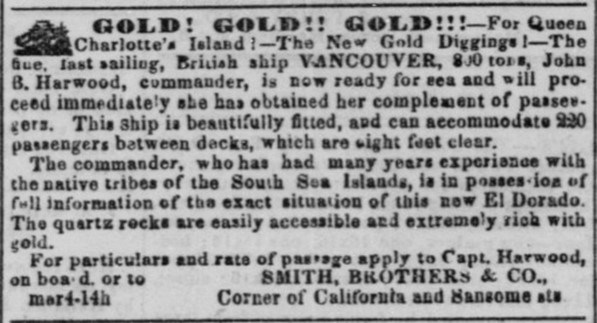

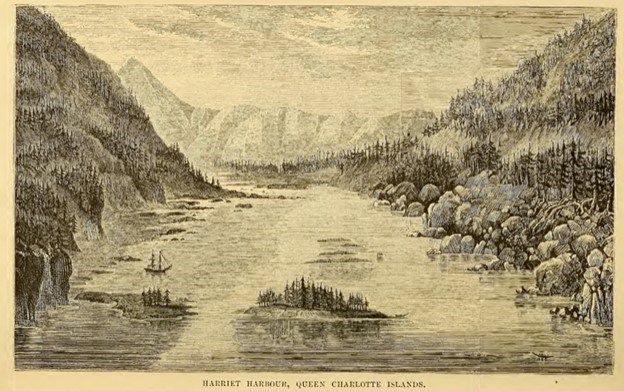

The Haida people were among the forefront of the maritime fur trade of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a trade with Europeans in seal otter pelts, so coveted in the Asian markets of the day. But less well known is that Haida Gwaii experienced a brief gold rush in the early 1850s (predating the Fraser and Cariboo rushes) that attracted many American ships to their coast. In all instances, the fiercely protective Haida beat these early intrusions back, and in at least one case ransomed an entire crew of gold seekers, after having burnt and fully destroyed their ship.

In the decades that followed, there would be many more excursions by foreign traders and miners who sailed into the waters of the archipelago – but while many sought peaceful trade, others took their chance to loot Indigenous treasures.

Here is a curious story of one such expedition I happened across recently, and of one singular artifact – possessed by at least a half-dozen individuals – before it was donated to a prominent California museum in the late 19th century.

The San Francisco Call newspaper reported, 7 April 1897, “the record of this ruin-tracked relic” and “where it has gone disaster and desolation have been rife.” The news item almost reads like stories of the curse of King Tutankhamun (though Howard Carter did not open Tut’s Tomb until 1922) starting with the tale of a seafarer who robbed an unspecified Haida village of a mysterious carving, among other antiquities.

To one Hans Anderson, an unscrupulous and sacrilegious follower of the sea, is attributed much woe of the past 30 years. This Hans Anderson was a trader who plied the Pacific Coast three decades ago. One evil moment he directed his vessel toward Queen Charlotte Island on the British Columbia coast. . . Anderson invaded one of the villages, ostensibly to do some small trading with the Indians, but with the real heart of a pirate. Awaiting a favorable opportunity he and his men on a dark night raided one of the native temples, if such they could be called, and carried away everything of value and everything that even looked valuable. Then came the retreat to the ship and a hasty setting of sail.

Among the articles taken that night “was a hideous carving” or, “idol” (as viewed through the European lens of the time). This enraged the Haida people. And so, while watching Anderson’s ship sail toward the horizon, they called upon their shamans to perform “a series of weird incantations” such that a “terrible curse and the worst luck” would follow all those who would posses it.

What happened next? Apparently Anderson subsequently sailed south to Vancouver Island…where he died in “horrible agony from convulsions.” Soon after, as he had owed a debt to the captain of a sealing schooner called the O. F. Fowler, Anderson’s assets were liquidated – including the mysterious artifact. The San Francisco Call reported:

The O. F. Fowler was as stanch a craft as ever sailed the main, but she could not sail with that ‘hoodoo’ aboard. The very first voyage she attempted with it as a passenger ended in disaster. She was crushed on the rocks and the captain and several of the crew were lost.

Following the shipwreck, the “Hoodoo” (a parapsychological power, or as the cause of harm which befalls the targeted victim) somehow floated ashore with the wreckage where it was retrieved by a fisherman. A week later, he too was dead, apparently due to a “brain fever.”

The San Francisco Call story then states the mysterious object made its way further down the coast in the possession of some whalers, selling the “cursed” artifact to a wealthy and prosperous San Franciscan by the name of Robert Llewelyn.

‘Bob,’ as he was familiarly known along the waterfront, never suspected the evil spell that possessed the curiosity, even when year after year, all sorts of financial reverses beset him and he saw his fortune dwindling away.

He finally found himself poor, and opened a little saloon with the hope of at least keeping the wolf from the door, and through all these years he never parted with the Indian idol. The climax came less than a year ago when poor Llewelyn fell down a flight of stairs and sustained injuries which caused his death.

Four deaths later, the artifact was next purchased by John Coyne, “a tinsmith and plumber” known for his collection of curios. “During the period of his possession . . . . he had all kinds of bad luck.”

‘Why, do you know,’ said Coyne, ‘while I had that confounded thing in my possession, my business went to absolute rack and ruin. Believe me, I could not get a thing to do, I couldn’t sell anything and I began to think seriously of closing my shop for good. That idol sat up on a shelf and seemed to grin all the broader the worse my luck grew. Finally I took it down and stowed it away in a little closet under the stairs, where I changed my clothes. And do you know, I went in there one day, and bless me if I didn’t see a wild-eyed Indian chief standing right beside that idol. But I am thanking my lucky stars that I got rid of it at last. I am satisfied that it is to blame for all of my bad luck.’

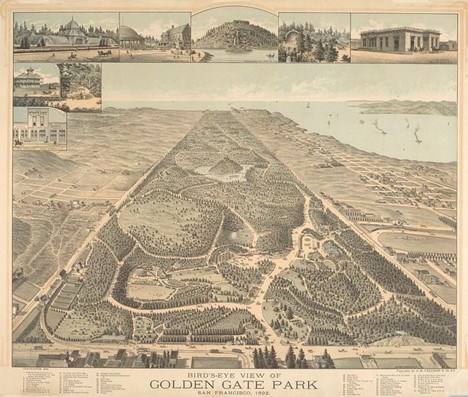

Coyne subsequently sold the Haida artifact to John L. Bardwell, a well-known collector of curios and antiquarian items. “I tell you it is a good thing for him that he got it off his hands right away,” Coyne said. Bardwell, “the most magnificent of benefactors,” had travelled to California in 1852 and his antiquarian collections were considered the finest on the Pacific Coast. Most were donated to the Golden Gate Park Museum, including, it seems, the mysterious Haida artifact.

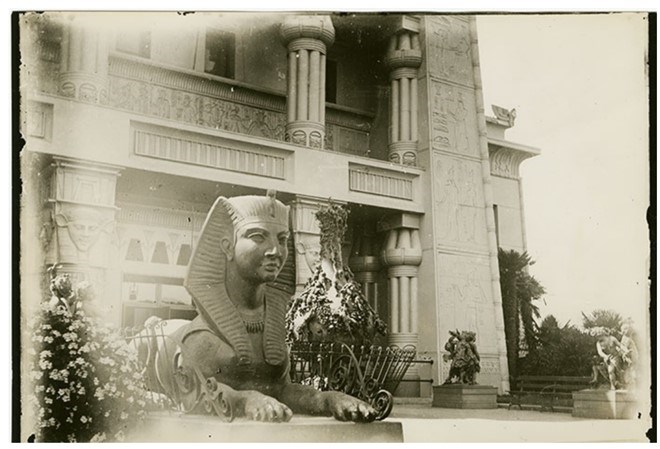

It is an old Indian idol that was recently discovered and purchased by John L. Bardwell – that indefatigable searcher for antiquities – and given by him to the Park Commissioners. A glance at the distorted and horror-inspiring carving is enough to convince anybody that even if the thing did not possess the power to wreck lives and homes, it ought to. Just what it is, or what it was ever intended to represent, not even the museum curators are able to divine.

The story does not end with the museum’s acquisition of the Haida object. Apparently, a whole series of mishaps followed.

First, a costly Oriental vase, “which had for months rested snugly and peacefully in one of the Park Museum niches,” fell off its stand and shattered on the museum’s marble floor, consigning it to the dustbin. “Scarcely an hour later another crash was heard” when an ornamental spire on the roof of the museum’s “Egyptian structure” smashed itself to pieces. “And the next day something else fell off its perch and again the day after that” – such that, the museum staff “began to grow extremely alarmed.”

Dr John Hays McLaren (1846–1943) – a close friend of the naturalist John Muir – served as superintendent of Golden Gate Park for 53 years. The laying out and supervising of the park earned him a worldwide reputation as a landscape gardener. Of the strange series of mishaps he apparently stated:

‘There’s a hoodoo around this place somewhere, and nobody can convince me that there is not,’ said Superintendent McLaren in a worried sort of way, when he was told of the mishaps, and had essayed to solve the mystery. ‘We will have to locate the thing and get it out of here, that’s all,’ he added with a determined shake of his head.

Then was inaugurated the search for the evil-possessed object that was threatening to totally destroy the park’s collection of antiquities. It was not until yesterday, however, that the ‘hoodoo’ was cornered, and now it is dollars to marbles that the thing, if allowed to stay in the park at all, will be relegated to some isolated spot out on the hills, where it will have little opportunity to exert its evil influence.

The San Francisco Call warned its readers that “People who visit the park from now on need not be surprised if their buttons pop off their clothes, if they stub their toes, slide on banana peels, or get knocked over by bicycles. It will be the work of that idol.”

What are we to make of this fascinating story? And what happened to the “hoodoo” – where is it today?

I began sleuthing archival records for the old Golden Gate Park Museum. Apparently, curators of the time had dedicated a room, among their many exhibits, to John L. Bardwell, their largest donor at the time. “Bardwell’s Old Curiosity Shop” contained hundreds of curios; the “hoodoo” was likely among them.

My endless search for the missing Haida artifact produced no immediate results. I began to wonder whether this rather fanciful story by a 19th century paper was true, or whether spooked museum officials had consigned the carving to the hills. Nevertheless, certainly there were other Haida objects in the museum, so I continued in my attempts to locate the provenance for Bardwell’s collections –– until, suddenly, I hit the motherlode. I found it!

Today, listed as a “Feast Bowl” (Accession Number: 5751) by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the catalogue entry confirms the previous ownership outlined in the 1897 news story. Under the listing for provenance it records not only that it was gifted by Bardwell that year, but that the previous possessors were indeed “Hans Anderson, sea Captain and trader, the Captain of the sealing schooner O.F. Fowler, Robert Llewelyn, San Francisco, [and] John Coyne, tinsmith and plumber, San Francisco.”

Eureka!

Did the San Francisco Call embellish this strange tale to drive attendance at the Golden Gate Park Museum? Perhaps, though the main elements of this puzzling story appear largely true – that is, but for one further perplexing riddle.

Today, Californian museum officials have catalogued the supposed “Hoodoo” not as a Haida artwork, but as “Kwakiutl” (Kwakwakaʼwakw), an Indigenous nation to the south of Haida Gwaii – no wonder it took so long to locate! And while museums have been known to make mistakes, I will leave further investigations to other interested parties who may want to follow the trail. Have a look at the link and keep me posted – the mystery continues!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall last wrote the amazing story of one man's journey from abject poverty in Victoria, to becoming the toast of New York and foremost economic thinker of his day.

- Daniel's two-part series on Canada's Westward Expansion explores the Big Question: how did we get here?

- Mayne Island's Grant Buday's historical novel Orphans of Empire looks at the very origins of the city of Vancouver.