How did we get here?

Just how did BC, the Northwestern Territories and Rupert’s Land come to be part of a Canada?

The Colony of British Columbia joined Canada in 1871, but Canadian designs of including BC into the coast-to-coast federation began years earlier – particularly with the Fraser River gold rush of 1858.

Access to the Pacific Ocean was the driving force to their ambitions to compete with the United States. Canada’s considerable knowledge of, and interest in, British Columbia is a point worth emphasizing. Many have advanced the argument that Canadian negotiators negotiated the BC Terms of Union without full knowledge of the unique aspects of the colony’s geography and policy developments – especially with regard to Indigenous land management issues. From an historical perspective this view is largely incorrect.

It has also been contended that BC’s previous and longstanding position of not recognizing Aboriginal title was not known. Therefore, it remained an unpaid debt and ongoing dispute.

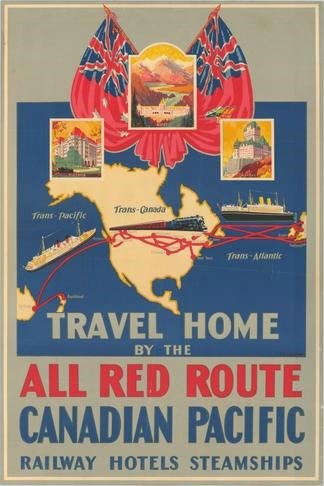

On the contrary, Canada’s knowledge of BC was quite substantial. There were many Canada-British Columbia connections that existed prior to 1871. First, Fraser River gold was an important impetus for a transcontinental British North America, the “all Red Route” that would ultimately span from coast to coast.

The Fraser Rush was considered the third great mass migration in pursuit of gold, following California and Australia. Not unlike the American government, the Canadian government was quick to learn all about the two Pacific Coast colonies (Vancouver Island and British Columbia) as part of its larger plans for westward expansion.

American westward expansion had already begun, with its acquisition of Oregon and California. The need to link these states to the east by building a transcontinental railway was soon considered and eventually realized. In particular, the incredible mineral wealth of California was a great impetus for immediate U.S. expansion. If Canada were to compete with the U.S., it would also need to expand westward, acquire further lands for colonization, settlement, markets and resources – and perhaps most importantly, access to the Pacific Ocean.

This necessitated union with British Columbia. Without BC there would not have been a Canadian equivalent to the American transcontinental nation.

There were many pre-confederation links between BC and Canada. Captain John Palliser had begun his explorations west towards the Rocky Mountains in search of a practicable route to the Pacific Ocean that build on earlier explorations, such as those of Simon Fraser (1808) and Alexander Mackenzie (1793).

As the historian E. E. Rich concluded, “the discovery of gold on the Fraser . . . made the British and Canadian governments alike more aware of the importance of preserving the route across the prairies” to link with the Pacific Slope.

Englishman Kinahan Cornwallis in The New El Dorado (1858) gave glowing accounts of BC in 1858 and concluded, “as to the probability of a railway being constructed from Canada to some point in British Columbia . . . . there can be little doubt.”

Alfred Waddington, member of the Vancouver Island Legislative Assembly, was author of The Fraser Mines Vindicated (1858), and one of the chief proponents of a transcontinental railway linking Canada with the Pacific Coast. But at approximately the same time gold discoveries were announced on the west coast, an 1857 select committee of the British House of Commons had agreed in principle to Canada’s “just and reasonable wishes” to annex the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) lands or the northwestern territories comprising Rupert’s Land, the vast land drained by rivers flowing into Hudson’s Bay, and the further and huge contiguous HBC fur trading districts that reached all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

This acknowledgement of Canada’s claim to the territory west of the Great Lakes heightened aspirations for westward expansion. Gold was discovered in the Fraser River that same year, and practical notions of a transcontinental state began to take shape.

The Fraser gold rush drew many notable Canadians to British Columbia, including future BC premiers George Anthony Walkem, Robert Beaven, John Robson, and the Nova Scotian Amor de Cosmos. Equally important, early Canadian migrants such as Walkem and Robson acted as political informants to prime ministers John A. Macdonald (Conservative) and Alexander Mackenzie (Liberal.

In the same year that Captain Palliser reached Fort Victoria, a number of Canadian-sponsored business enterprises sprung up, intending to profit from a new transcontinental connection. The “Canada Agency Association Limited” proposed they be made sole agents for the sale of Crown lands in Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

The issue of harmonizing currencies was discussed by the British Colonial Office, “the wisest course to be adopted in the case of the currency of British Columbia will be to assimilate it to that of Canada.” The British War Office acknowledged a letter from the Governor of Canada that a volunteer calvary corps in Upper Canada solicited “permission to raise a force of one hundred men for service in British Columbia.”

They were by no means alone. The “North West Navigation and Railway Company of Canada” offered to run a postal service across the continent. Lord Carnarvon saw the “great political advantages” of this scheme, which would “probably go far to facilitate the erection of colonies, the development of natural resources & the consolidation of B.N. America as part of the Empire.”

Arthur Blackwood, Senior Clerk in the North American Department of the Colonial Office, believed that a transcontinental route was an invaluable asset if relations between the United States and Britain worsened in Central America. “If a war should break out with the U. States interrupting our maritime communication with V.C. Isl[an]d & B. Columbia [he stated] we have the consolation of knowing that we can still fall back upon this overland route.”

Clearly, from the Canadian perspective, BC was not the terra incognito claimed later.

British Columbia was encouraged by both the Canadian and imperial governments to join confederation. The colony ultimately accepted primarily for relief of its accumulated debts due to its extensive roadbuilding program, and the additional incentive of a continent-wide railway system.

The federal government of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald met, if not exceeded, all of British Columbia’s conditions for political union. Where there might be disagreement, such matters were largely left unresolved in order to win BC’s acceptance of the final terms.

In other words, Canada made a number of offers and concessions that effectively ignored difficult questions. Part II of this series will demonstrate this, and explore the BC Terms of Union in greater detail; specifically Article 7 (Canadian system of tariffs), Article 11 (the transcontinental railway), and Article 13 (federal responsibility for Indigenous peoples). Each one highlights Canada’s strategy of delay to secure its main objective of access to the Pacific Coast.

With the introduction of the Canadian Tariff structure came huge losses to the agricultural interests of the new province, a railway promise that fractured BC’s political landscape that fuelled the threat of secession, and the attempted harmonization of BC into a made-in-Canada Indigenous policy that continues to haunt the Pacific province to this day.

Stay tuned!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's last piece was a ripping good yarn - of a future Speaker of the Legislative Assembly getting lost in the mountains in a winter storm...on Christmas Day.

- As Daniel notes, Aboriginal title is still an issue to this day. Bob Price wondered what UNDRIP will mean for the province's resource sector.

- Carol Anne Hilton offers a different perspective on UNDRIP, and what it will mean for the average British Columbian.