Viewing the 1858 BC gold rush from the other side of the world, Colonial Office officials in London could only see so much.

They had little information about the rapid immigrant flow of some 30,000-plus gold seekers who had quickly crossed the 49th parallel.

Lord Lytton addressed the British Parliament:

This is not like other colonies which have gone forth from these islands; and of which something is known of the character of the colonists. . . As yet the rush of the adventurers is not for land but gold, not for a permanent settlement but for a speculative excursion. And, therefore, here the immediate object is to establish temporary law and order amidst a motley inundation of immigrant diggers, of whose antecedents we are wholly ignorant, and of whom perhaps few, if any, have any intention to become resident colonists and British subjects.

The immediate institution of “temporary” law and order begs the question: why did not the imperial government mandate fully constituted law and order?

Once again, Lytton’s words are indicative of the clouded realities of a colonial project mired in the chaos of a frontier gold rush.

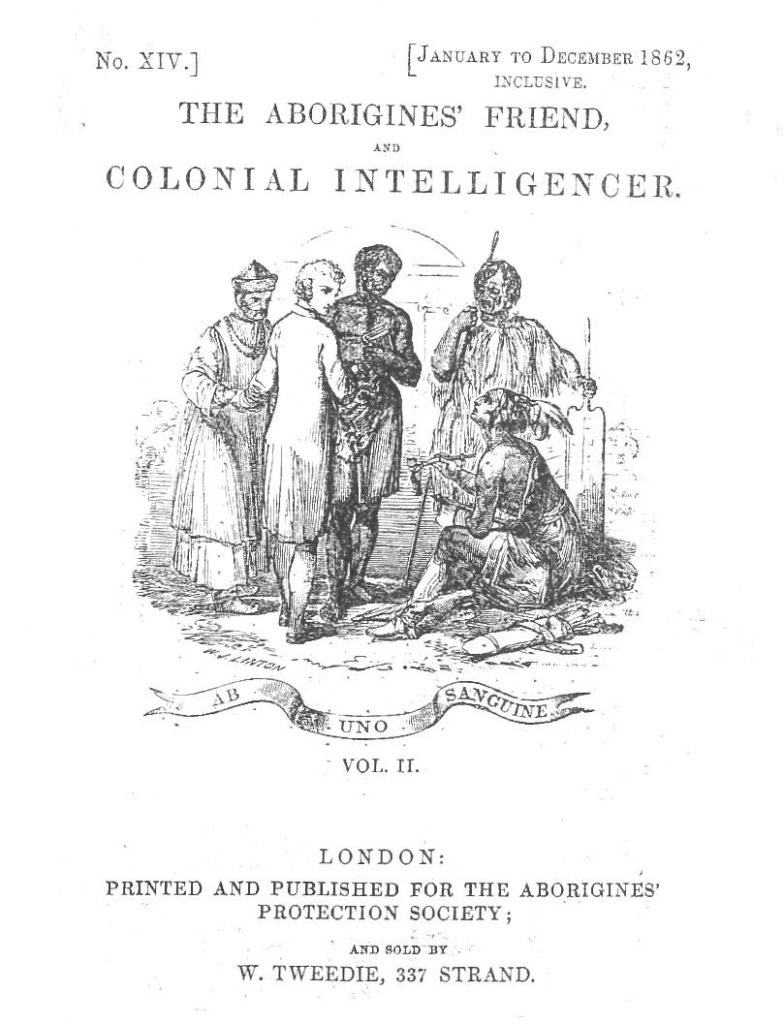

Put simply, the imperial government did not have sufficient information to form hard and fast policies. Their sole aim – as advocated by the influential Aborigines Protection Society – was to assert British sovereignty and the spirit of liberal humanitarianism (though waning) against a rapacious mining frontier in order to save Indigenous lives.

Unlike the earlier Crown grant of Vancouver Island to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) – stipulating that the monopoly was responsible for promoting an orderly agricultural settlement – the protection of Indigenous peoples in mainland British Columbia was the sole and paramount concern. Permanent land disposal policies that defined settlement would have to wait until a clearer picture emerged of the chaos of the gold rush.

“[T]he most pressing and immediate care in this new colony,” argued Lytton, “will be to preserve peace between the natives and the foreigners at the gold diggings.”

Indeed, Henry Labouchere, Lytton’s predecessor as Secretary of State for the Colonies, warned “there was one circumstance which constituted the main danger of disorder, and that was the strong aversion which the Indians entertained towards the Americans.”

“This colony was not like Australia or New Zealand,” warned the Duke of Newcastle, “as remote from great Powers as from England -- it was near to great Powers, but remote from us.”

The mainland colony’s situation did not fit the formal models of colonialism practiced elsewhere in the British Empire. The close proximity of the United States and the “great danger” of native-newcomer conflict spreading across the border urged upon Lytton the necessity of giving “all the power they could to the only authority at present in the colony – the Governor.”

The establishment of the Crown Colony of British Columbia was a hastily-fashioned attempt to provide “temporary law and order” and the assertion of British sovereignty as quickly as possible.

The gold-seeking community the British government sought to rein in was “so miscellaneous, perhaps so transitory, and in a form of society so crude” that James Douglas’s appointment was provisional until a clearer picture had been gained of the foreign population whose sympathies were “decidedly anti-British.”

With the fall of Lord Palmerston’s government in February 1858, British public opinion had turned increasingly against monopoly privilege of Crown-chartered companies, such as the HBC.

Lytton, a member of Lord Derby’s new cabinet, joined a ministry deeply suspicious of the HBC’s commitment to further colonization in Vancouver Island. But at the same time, HBC policy and their centuries-old relations with Indigenous peoples was deemed successful, and held by imperial authorities in high esteem.

Because of this, James Douglas – through his long years of association with the fur trade – was ultimately chosen governor, instead of a British-born career civil servant.

In the first year, the imperial government issued only two main directives for Douglas to follow: (1) Ensure the welfare and protection of Indigenous peoples (as opposed to the California experience); and (2) that in formulating any Indian Reserve policy (for which Douglas was given complete authority) that non-native settlement take precedent and the material progress of the colony not be thwarted in any way.

This last point was made plainly clear by Lord Carnarvon:

whilst making ample provision under the arrangements proposed for the future sustenance and improvement of the native tribes, you will, I am persuaded, bear in mind the importance of exercising due care in laying out and defining the several reserves, so as to avoid checking at a future day the progress of the white colonists.

These were Douglas’ primary instructions during the critical first year of B.C.’s development as a provisional colony. Neither the proprietary Colony of Vancouver Island nor the Crown Colony of British Columbia were excluded from the paradoxical policy “to protect the poor natives and advance civilization.”

The Derby government was committed to enforcing a policy of self-sufficiency on newly-emerged colonies like British Columbia. Lytton adamantly encouraged Douglas to practice “the strictest thrift at the onset” so that when responsible institutions were finally inaugurated in B.C. the colony would be “unembarrassed by a Shilling of debt.”

Self-sufficiency and economic retrenchment were central tenets of the new Derby government, so much so that Lord Lytton expounded on the necessity of adopting these “thrifty” measures:

I cannot too early caution you against entertaining any expectation of the expenses of the colony under your charge being met at the outset by a considerable Parliamentary Grant. . . . I am fully satisfied that parliament would regard with great disfavor any proposal of a gift or a loan to the extent you suggest. . . . But I cannot avoid reminding you, that the results, even if the object could be attained, would, according to all past experience, be of a very questionable character. The lavish pecuniary expenditure of the Mother Country in founding new Colonies has been generally found to discourage economy, by leading the minds of men to rely on foreign aid instead of their own exertions, to interfere with the healthy action by which a new community provides step by step for its own requirements; and to produce, at last, a general sense of discouragement and dissatisfaction.

For a Colony to thrive and develop itself with steadfast and healthful progress it should from the first be as far as possible self supporting. I can assure you that in bringing these general considerations under your notice, I by no means overlook the special circumstances of the case of British Columbia, nor do I at all under estimate the difficulties and the anxiety which they must occasion you. But I need not impress on one so accustomed as yourself to the details of public business and the conduct of financial enterprises that, even under more unfavorable prospects than those of a Colony of which the resources, along with the necessities are rapidly augmenting, there is room for exercising the control of a judicious economy, and for adapting your objects to such means of attaining them as you may possess.

To Lytton’s mind, if colonial finances were lacking, then Douglas must adapt his policies to fit the financial restrictions:

Douglas agreed. With no guarantee that gold rush revenue might continue, Douglas practiced a strict economy and adapted colonial policies and projects to the limited means at his disposal, as Lytton had urged. But the Colonial Office also was well aware of the new colony’s unique circumstances, and decided to place relatively few demands on Douglas, preferring instead to rely on his expertise.

Queen Victoria’s paradoxical policy of protecting Indigenous people while promoting progress presented colonial administrators like Douglas with an onerous task: to interpret and implement two mutually exclusive imperial goals.

In part, this dilemma explains the infirm and often contradictory nature of early Indian reservation policy during the colonial period. The Indian reserve was considered both a refuge for Indigenous peoples from newcomer encroachment, and an impediment to progress.

Consequently, the administration of crown lands might shift and adapt its focus, depending on a given administrator’s interpretation.

With the imperial government providing no grants or loans, yet still demanding costly road-building be implemented immediately, Douglas did indeed adapt his policies to the limited means at his disposal. At times, economic circumstances meant that Douglas had to severely cut expenditures to the bare bones. In 1863, Douglas would not even draw his personal salary in order to sustain Vancouver Island’s elaborate road-building program, that year’s single largest budget expenditure.

The provisional governor of the mainland was adapting even at his own apparent expense.

The limited economic means better explains the historical context of colonial Indian reserve policy in British Columbia. More succinctly, if there was little to no financial resources available, it makes sense that neither settler lands nor Indian reserves would be formally established and legally confirmed until the colony could afford them.

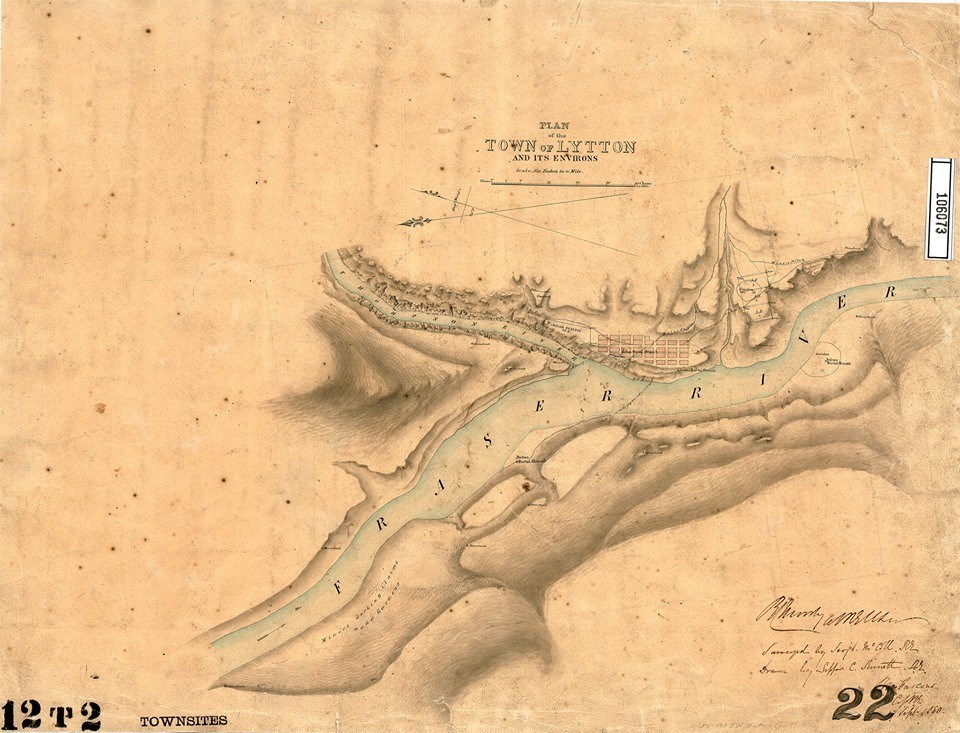

Consequently, Douglas announced the system of Anticipatory Indian Reserves in 1859 and the Preemption Act of 1860; both preceded formal surveys, but were clearly adaptations to severe financial strictures.

Shielding natives from the onslaught of newcomers was described in the language of welfare and protection, while “Progress” in newly emergent British colonies was predicated on two main land management goals: (1) the requirement for formal land surveys in advance of settlement; and (2) the quick development of routes of communication, particularly road-building.

The Colonial Office deemed formal surveys and the construction of roads and bridges to be highest priority; without them, the provisional colony of BC would remain just that – provisional – or conceivably no colony at all.

A fully surveyed and accessible land-base was the only means by which a colony would succeed within the limits of imperial policy.

The imperial government was no longer prepared to foot the bill, so the sale of lands was seemingly the only means by which revenue could be raised to pay for surveying and construction of roads. The adjacent Colony of Vancouver Island was hampered the Wakefield system – which had been practiced in Australia – compounded by the close proximity of the U.S. that had instituted a preemption system that forestalled the need for expensive and formal surveys, and hence inexpensive land was readily available. The American Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 stipulated that a married immigrant couple “could acquire a 640-acre tract of farmland” for little to no expense.

As such, new immigrants were not particularly attracted to Vancouver Island prior to 1858 due to land prices being set comparatively high (£1 per acre). Douglas knew a similar policy in the mainland colony would not foster agricultural settlement. Internal debate within the Colonial Office realized that the land policies adopted in Australia would not work in B.C. – but at the same time, they were anxious that expediting settlement prior to formal surveys would ultimately lead to confusion and future litigation – how prophetic!

By 1860, the stark realities of a provisional colony still without any formal land disposal policy suggested to Douglas the only means by which the temporary colony might become permanent.

In the absence of a settled imperial land disposal policy, Douglas exercised his local authority, and instituted the American-style Preemption Act and the Anticipatory Reserve system. Both solved the immediate problem of the need for expensive and formal surveys, and even at the risk of precipitating future confusion and “expensive litigation.”

As we all know, “expensive litigation,” has become one of the legacies we continue to grapple with today!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.