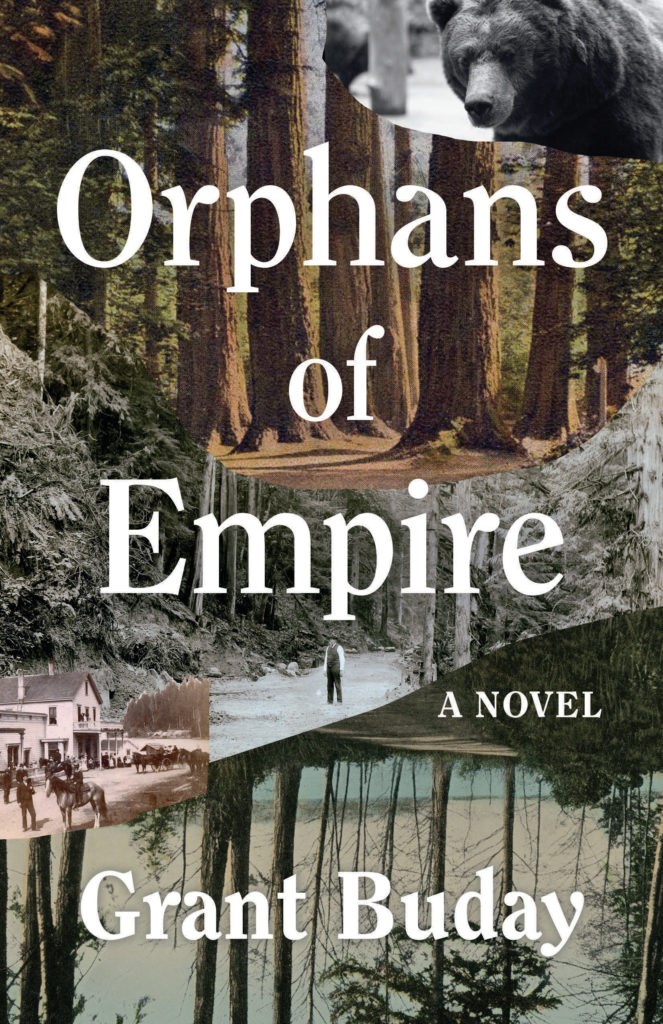

Editor's Note: The following is an except from Orphans of Empire, a new historical novel from Mayne Island's Grant Buday. It tells the story of of the original site of Vancouver on Burrard Inlet, via three voices in three different decades—Sir Richard Clement Moody, who was tasked with creating a New Britain in North America, Frisadie, a Hawaiian entrepreneur who purchases a hotel, and in this excerpt, Henry Fannin, a magnet enthusiast and romantic who falls in love at the hotel decades later.

FANNIN – 1886

New Brighton, Province of British Columbia

Henry woke to the rolling roar of hard wheels on a fir floor. Lying in the dark he admired the resonance, which, even at half a furlong, caused such a satisfying sensation throughout his skull. He was lying on his bench beneath a horsehide coat lined with sheep’s wool. The bench was a slab of Douglas fir that served as a good corrective for the curvature of his spine, which was apt to cause stabbing pains in his hips and neck. In the throes of such spasms he’d lie panting on the slab and recall the Stalwart, in which he’d come up the coast, whose cables and timbers had groaned and strained like the rigging of his own body.

Along with the sound of wheels on wood he heard the ringing of frogs and the small heave and slap of waves, as well as a breeze stirring in the newly leafed maples. Isolating sounds had become a means of diverting himself from pain. His many books on mesmerism had advised this. Put your mind somewhere else, as if his mind was a hat that he might remove at will, and sometimes it worked. If he put his mind to it, if he bore down on the task, his mind could, if only briefly, trick itself into looking the other way.

He sat up with the care of one uprighting a vase. Light-headedness sluiced his skull and he waited for it to settle, found his lucifers, scraped one against the sandpaper strip on the box and lit his oil lamp, and saw by his watch that it was gone 4:00 am.

The eyes of his animals gleamed with a preternatural brightness. He’d had their glass eyeballs sent up to Victoria and then across to New Brighton from Germany via San Francisco, but it was not only the quality of the glass, but the fact that he put a piece of lodestone in each creature’s skull. Henry’s business was still small, but all who saw his work remarked upon the animation of his animals and the lustre of their eyes.

His was an art dating to the pharoahs, and if his clothes smelled of fur and feathers and formaldehyde he rated it a mark of distinction no less honourable than that of the incense pervading a priest’s robe. His menagerie included the head of a noble black-tailed deer and one of a snarling cougar. There was also a river otter, a raven, a pileated woodpecker, a pair of whiskey jacks, and his ducks.

In the five years since leaving London he had crossed the Atlantic and then the United States and approached every embalming parlour en route. At Roswell’s in Brooklyn he had foolishly announced his theory about putting lodestones in the subjects and was laughed out the door. Burnett’s in Chicago had taken him on and yet it soon became clear that he would never be allowed to do more than swab floors and sluice drains. When he quit he was relieved that he had discovered enough discretion to have kept his ideas regarding magnetism to himself.

In Sacramento a man called Gillings had taken him on but then proceeded to make unnatural advances. In San Francisco he found work in taxidermy. Admittedly, this was embalming’s poorer cousin, yet it shared many techniques and he learned to respect it. He stuffed foxes and wolves and eagles, and he might well have stayed in San Francisco, for he liked the hills and the sea and Chinatown and the coming and going of ships, but the tide of people flowing north to British Columbia, the Queen’s domain, a bit of England on the Pacific, swept him along.

Seated cross-legged on his bench in his stump house, Henry listened to the swirling sound of rolling wheels. “Mr Black,” he said aloud, and considered what a deeply troubled man was the Laird of New Brighton to be roller skating at such an hour. Henry looked to his collection of magnets and lodestones in the glass-fronted cabinet, for he believed that in magnetism there lay an answer to both Black’s dilemma and his own.

He’d become a student of Franz Mesmer and Maximilian Hell, pioneers in the field of magnetism’s wide-ranging effects on the human mind and heart. In the cabinet were four tin hearts, and the lodestones that would fit inside them, wanting only another few days’ work to complete. He was putting his faith in them to draw love back into both his life and that of George Black.

He picked up The Mighty Curative Powers of Mesmerism from his night table and opened it to a drawing of a fiercely frowning Franz Mesmer, hair and cravat awry, hands raised in a gesture of incantation. The preface spoke of Mesmer’s early life and influences, his interest in astronomy and medicine, culminating in his theory of animal magnetism, viz. that there existed a vitalizing energy that communicated between all things both animate and inanimate, and that the skilled practitioner could focus and direct it.

The Monks of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Singers of Gregorian chant, the Yogins of Hindostan, the Priests of Tokio, the Indians of New Mexico, from Antiquity unto the Present, all were and still are Adepts at primitive forms of Mesmerism, utilizing both Sound and Gesture in Hieratic Formulas intended to Induce a State of Receptivity.

Receptivity. Setting the book aside, Henry swung his legs down and his bare feet pressed the floor that was simultaneously gritty with beach sand and felted with animal hair. He unbuckled his Heidelberg Electric Belt, stepped out of it and placed it in the cabinet, then rubbed at the red indentations it always left in his hips and thighs and buttocks. He pulled on his denim pants and looped the suspenders over his shoulders and then tugged his boots onto his bare feet. They were good boots; he’d made them himself.

He tugged the peg from its slot and the door drifted open. It was damp and cool in the pre-dawn, it having been a wet April and so far a drizzly May, and at the moment there were both stars and clouds, and a small breeze meandering up the inlet. As always the air smelled of woodsmoke, dried fish, pig shit, and, it being spring, sap. His stump stood high up the slope and had a view of the lights of the sawmill half a mile across the water of Burrard Inlet, while off to his right stood Black’s roller skating hall beneath a quarter moon.

Carrying his oil lamp, Henry angled his way through the trees across the slope, the frogs falling silent as he approached and resuming their ringing as he passed. The circling roar grew clearer. The hall had been built as a barn, then Black laid down inch-thick fir planks sprung with horsehair and began using it as a dance hall and banquet room and most recently as a roller skating palace.

The sliding door was open. Even as Henry stepped in he had trouble believing what he saw, or rather what he did not see: Black was roller skating in the dark, without so much as a lamp or a candle. Remaining near the entrance, Henry listened while his eyes adjusted. The wheels rolled like stones in a barrel, rumbling low and relentless, as though they had been travelling through the ages, from the past to the future via the present, across steppe and prairie and desert with no destination other than the pure pursuit of speed and distance, and it seemed that the wheels travelled in blindness, as though guided by some other means beyond the ken of Man.

Henry had seen blind men tapping along the lanes of London and New York and Chicago and San Francisco, their sticks bobbing like the antennae of beetles, yet even the most confident moved slowly; Black sped, drawn as though by a magnet. Henry heard him cross-stepping into the far turn, skates tapping and scraping and the sound changing as he swung hard around the bend and came plunging toward him.

He held the lamp high to be sure Black saw him.

“Henry!”

“George . . .”

Black loomed up out of the dark and shot past in a rush. The noise of the wheels receded to the right and then warped as Black leaned once more into a turn. Eyes adjusting, Henry now discerned Black’s gliding shape and imagined a ghost rider, an enigmatic Hermes bearing a message from the afterworld, or perhaps from the past, from out of the night, and envisioned an entire flock of such messengers hieing through space and time.

He found a seat on one of the benches, blew out his lamp, and then leaned his head back against the wall so that the vibration of Black’s skates shivered up through his feet, through his pelvis, and up his spine into his skull. He placed his palms flat on the bench on either side of him, shut his eyes, and listened to the wheels rolling around the rim of the hall. When he opened his eyes the hall was a shade brighter, for dawn was approaching and it revealed Black skating backwards in a crouch, one leg out like a Russian dancer.

“You don’t think it dangerous? I mean, in the dark?” asked Henry when Black hove to and joined him on the bench.

“Not a jot.” Black drew a flask like a card from an inner pocket and for a while they passed the rum, savouring its sweet corrosion in their mouths.

“I miss my girls, Henry. They had lovely warm hands.”

Henry felt his eyes simmer with tears. He swirled the last of the rum in the flask, pretended to drink, and then passed Black the final swig. Henry missed them too. Or one of them: Leonora.

Grant Buday is the author of the novels Dragonflies, White Lung, Sack of Teeth, Rootbound, The Delusionist, and Atomic Road, the memoir Stranger on a Strange Island, and the travel memoir Golden Goa. His novels have twice been nominated for the City of Vancouver book prize. His articles and essays have been published in Canadian magazines, and his short fiction has appeared in The Journey Prize Anthology and Best Canadian Short Stories. He lives on Mayne Island, British Columbia.

SWIM ON:

- Orphans of Empire was also reviewed by The Ormsby Review, which last year lost its namesake. Daniel Marshall pays tribute to a BC institution.

- More book excerpts? Don't miss Michael Layland's In Nature's Realm, about the very real story of the HMS Topaze, and the remarkable natural historian who disembarked on Vancouver Island.

- May Q. Wong told the story of the first non-British settlers in Victoria - Black Americans.