Over the years I have been fortunate to stay at one of the oldest-remaining houses along the lower Fraser River from the gold rush period: the historic Teague House of Yale.

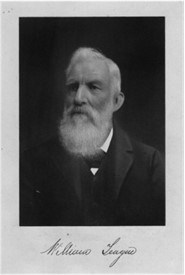

Built in the 1860s, this extraordinarily well-preserved home had a succession of colourful owners (including Andrew Onderdonk, CP Railway Engineer), but primarily the family of William Teague. Like thousands of others, Teague had been swept up by the Fraser River Excitement of 1858. Teague had mined at Cornish (or Murderer’s) Bar south of Hope, and soon held a number of early government appointments from early policeman to later-day gold commissioner, or government agent.

Many a night I would sit on the old veranda, overlooking not only the mighty Fraser rolling by, but the original Hope to Yale road (found directly below this house) that my great-great-great Uncle William rebuilt in the 1870s.

As both Teague and my ancestor were ‘58ers and from Cornwall, England, it was easy to imagine these two sharing the occasional cup of tea at this very home – a home still filled by Teague’s books and other possessions, even his original top hat!

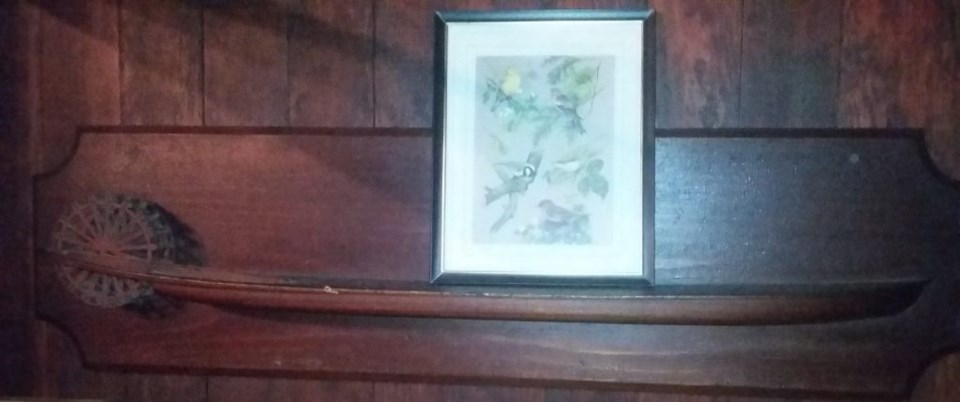

But there is one fascinating curiosity that has gripped my attention for decades: mounted on a 19-century plaque, there hangs a stern-wheel steamship hull, the aged wood from which it was fashioned looking decidedly old, its darkened colour hinting of its significant age. “What is the story of this amazing piece?” I asked my friends Sue and Darwin Baerg of Fraser River Raft Expeditions, the current owners of the Teague House.

“Oh that!” they said, their eyes sparkling. “It came with the house and the descendants of the Teague family. They say it has always been here.” Beyond that nobody seemed to remember much more about it – but I think now, years later, I may have uncovered some significant clues!

Here is the story of my recent research to learn more about this mysterious gold rush curiosity.

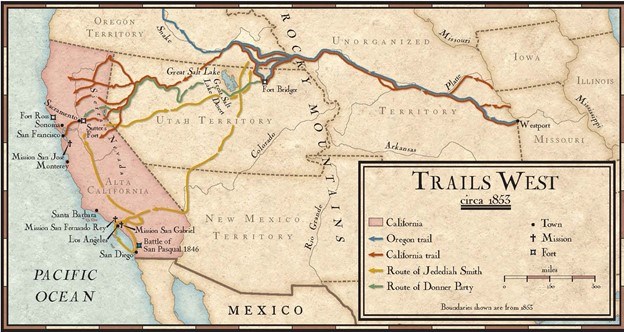

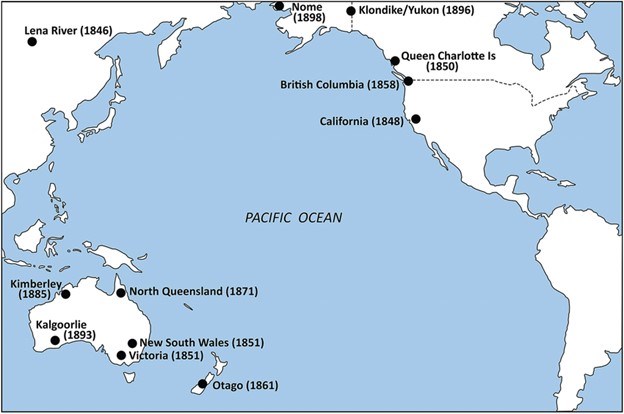

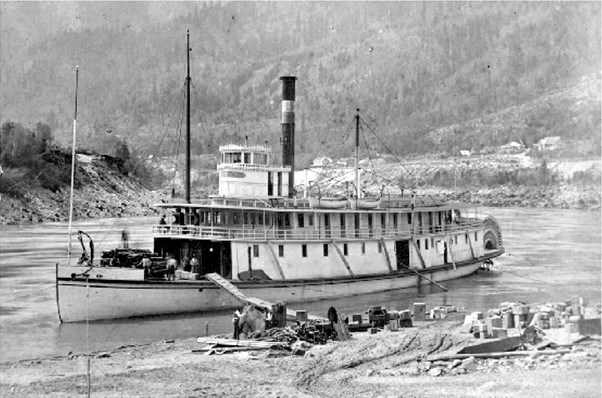

Yale, the height of steamboat navigation on the Fraser River, was initially unreachable in the early months of the gold rush. The strong currents and shallow portions of this immense stream prevented so many of the first ships from reaching the epicentre of this third great rush of gold seekers in recorded history.

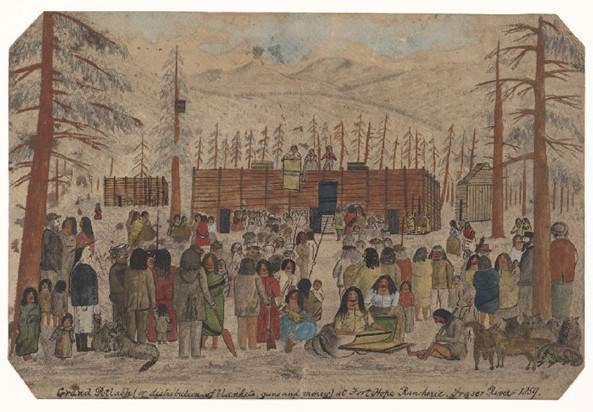

The original steamers, coming quickly from Oregon and the Columbia River (and later San Francisco) could only make it as far as Fort Hope; that is, until more powerful shallow-hull ships were designed for use on the Fraser River.

This was a key development in the early history of the gold fields; the boom-town of neighbouring Whatcom on Bellingham Bay, Washington Territory, threatened to supplant Victoria as the major control point of the new El Dorado, in large measure due to an American initiative to blaze a trail across the 49th parallel to the adjacent gold fields. To get beyond Hope, early gold seekers relied heavily on the expertise of Indigenous peoples who offered canoe transport to Fort Yale of both miners and goods.

In short order, Coast Salish peoples (particularly the Stó:lō nation) were employed to cut firewood and act as deckhands, their vast years of river experience by canoe was invaluable. One in particular, “Captain John,” piloted steamboats and according to his own reminiscences (given in Chinook and translated in 1898), he amassed some $2,000 from his labours. Jason Allard, son of HBC Chief Trader Ovid Allard, recalled when the native pilot was first taken aboard the American Steamer Surprise, anchored off Fort Langley in June 1858.

The pilot was an Indian named Speel-Set [recalled Allard]. He went aboard the Surprise barefooted and wearing only a blanket. When he returned he came as 'Captain' John dressed in a pilot cloth suit, white hat and calf skin boots, the proudest Indian in the country. More over the sum of $160 was paid through Mr. [James] Yale for the pilot's services – eight twenty dollar gold pieces. The boats thereafter ran to Hope more or less regularly.

While the participation of Indigenous peoples was key to the early transportation needs of the gold rush, with increasing numbers of gold seekers and the demand for more efficient and greater lines of supply, there also was a growing concern to conquer the swift currents and treacherous rapids above Hope with new ships built and fortified for the express purpose of reaching Yale.

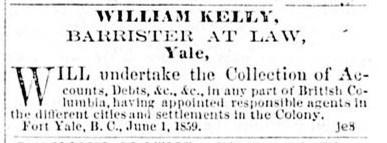

Enter William Kelly: a transnational gold seeker who in 1849 had crossed the American Plains to California, then to Australia and subsequently British Columbia in 1858.

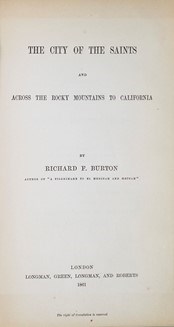

An Irish-born lawyer (I have searched in vain for a photograph of him), Kelly published his account of travels to the California gold fields – a book that subsequently inspired the legendary explorer Sir Richard Burton to follow in his footsteps. Burton later published his own account of crossing the continent to California.

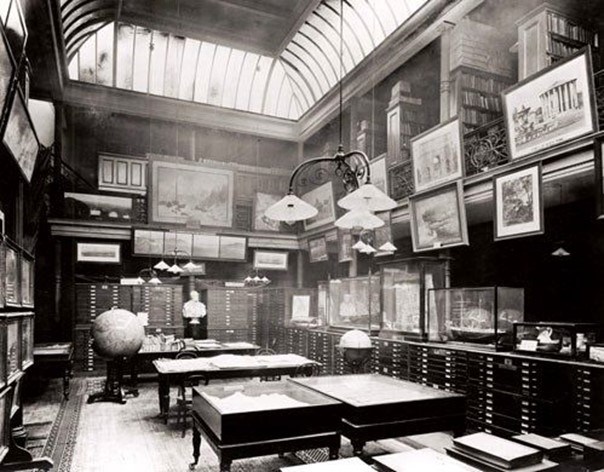

In fact, Richard Burton subsequently nominated William Kelly for membership in Britain’s prestigious Royal Geographical Society, becoming a fellow member in the early 1860s. Joining this august group would be beneficial to Kelly a few years later.

While in St. Louis, Kelly remarked on the allure of gold in California:

. . . the further west I proceeded, the more intense became the California fever. California met you here at every turn, every corner, every dead wall; every post and pillar was labelled with Californian placards. The shops seemed to contain nothing but articles for California. As you proceeded along the flagways, you required great circumspection, lest your coat-tails should be whisked into some of the multifarious Californian gold-washing machines . . . Californian advertisements, and extracts from Californian letters, filled all the newspapers; and ‘Are you for California?’ was the constantly recurring question of the day; so that one would almost imagine the whole city was on wheels bound for that attractive region.

This mania described by Kelly is exactly what occurred less than ten years later in the Fraser River Rush. In Australia, he also published on his experiences there – a regular commentator in the press – and notably argued for Chinese inclusion in the goldfields.

But when the Fraser River Excitement hit, he – like so many others – was once again swept into the mania that quickly transformed what would become British Columbia, the transformative influence that also shape-shifted other economies of the North Pacific Slope: Washington, Oregon and California.

Kelly, already heading to British Columbia before his second book on Australia was published, forecasted from afar the richness of the New El Dorado of the north. Writing in Life in Victoria (1859), Kelly stated:

I have not the slightest doubt but the discoveries in British Columbia will offer a temporary check to Australian development, because the climate and soil of the new colony are more in character with that prevalent in the British and European area, from whence the stream of emigration was wont to flow towards the antipodes, and because the pursuit of gold-getting there is so much simpler, speedier, and cheaper. In Victoria [Australia] the digger has to penetrate through the obdurate bowels of the soil to depths varying from thirty to three hundred feet, and perhaps, after a vast expenditure of time, toil, and money, he may come upon a barren bottom, whereas in British Columbia he has only to stand on the bar of a river, or throw back the mere alluvial deposit along its banks, in order to come at his rich reward.

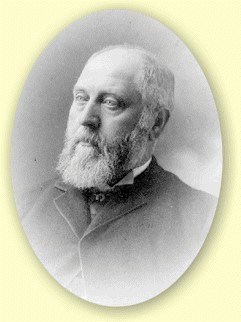

Arriving in British Columbia in 1858, Kelly established himself in a small shack in Yale, hanging his shingle out as a lawyer, where he became good friends with David W. Higgins, later the Speaker of the BC Legislature, who had also caught the gold bug and decamped from San Francisco in the same year.

Also an author in later years, Higgins described his first encounter with the argonaut of the Californian and Australian rushes. In his book The Mystic Spring (1904) he recorded how he had become homesick for San Francisco, wandering along the foreshore of the town of Yale:

My spirits continued to droop, the melancholy roar of the river as it lapped the huge boulders and the gathering darkness adding to the sombre hue of my mind and deepening my dejection. What might have happened had my thoughts led me further on it is impossible to say, but when a cheery voice in a rich Irish brogue broke the stillness with, ‘Good evening, sir; I hope you are enjoying your walk,’. . . My interlocutor was a stout, full-bearded man of about forty-five years. He was very neatly dressed in some black stuff, wore a full brown beard, and was very stout. In his hand he carried a heavy walking-stick. ‘I Thank you,’ I replied, ‘but I am not enjoying my walk a bit. I was just wishing myself well out of the place.’

Kelly, veteran of the Californian and Australian rushes, took the young Higgins in hand:

‘Tut, tut,’ replied the man, ‘you are suffering from nostalgia. Come along with me, my lad, and I'll give you something that'll drive dull care away.’ Before I could utter a word of remonstrance he had linked an arm in one of mine and led me off towards a little cabin or shack that stood not far from the trail on which I had been pursuing my walk. There, having lighted a candle, he produced a bottle of brandy and a pitcher of water, and insisted on my joining in a glass. He soon became very communicative, and after telling me that his name was William Kelly, a Trinity College man and a barrister, who had passed several years in Australia, and having been attracted to the Fraser River by the reported gold finds on the bars, had decided to try his fortune there. He had also written a book on Australian gold mining adventures, which had been printed in London . . . he had a fund of anecdote and could tell a good story, of which I was and still am passionately fond.

Kelly quickly perceived that unlike California and Australia, BC was hampered by its transportation links to the outside world, particularly getting steamers up past Hope.

While this was the California Rush repeating itself, it was different in that steamboat technology made the northern goldfields comparatively accessible; soon a gold seeker in San Francisco could walk down a gangplank, board a ship, travel to Victoria, take a further steamer across the Salish Sea (Strait of Georgia) to enter the mighty Fraser River and eventually walk one more gangplank onto the beaches of Yale. Imagine that!

To make that final leg, one great difficulty still had to be surmounted – and Kelly, among others, proposed the solution: specially-prepared and powerful shallow-hull steamers that could conquer the rapids and swift currents beyond Hope.

One of the main reasons the Fraser Rush had subsided quickly was the lack of infrastructure: roads, bridges, and steamers that could push forward, and supply lines of essential goods for an ever-expanding and far-removed field of gold strikes. There is much more to Kelly’s story than presented here, but on the question of improved steamboat communication, Kelly ultimately left Yale and British Columbia to make his case to the Royal Geographical Society in 1861-62. In fact, he spoke to assembled members just a year after John Speke (Sir Richard Burton’s former expedition partner in the African continent) with regard to the Fraser River gold fields.

Kelly’s presentation entitled “British Columbia and the Proposed Route from Pembina to Yale” is found in the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (Session 1861-62). In some ways a promotional piece that encouraged emigration, while noting BC’s disadvantaged position as compared to Australia and the United States. But of more particular interest, on 12 May 1862 Kelly exhibited “A Model of a stern-wheel Steamboat, adapted for the navigation of the Fraser River.”

Was this the curious model that hangs in the Teague House – or perhaps a copy of the same such model?

Apparently, this style of model was in common use. Known as a ship builders half-hull model, the art of making half-hulls is as old as ship building itself.

Half-hull models were originally made as a design tool, but also as a marketing and investment display. Often several models were made before the completion of a full-size ship. To my mind, Kelly presented one such copy of a shallow-hulled model, and I have a hunch that the curious Teague House antique may well be the other half of Kelly’s exhibit presented at the Royal Geographical Society.

What happened to William Kelly after his presentation to the Society’s members? Oddly, after having published widely on his expedition to California and experiences in Australia, Kelly abruptly disappeared. Apparently he had been writing yet another volume of travels – this time to the Fraser River gold fields and British Columbia. This work was neither completed nor published.

Again, what happened to this transnational gold seeker?

If we once again turn to the work of his friend David Higgins a persuasive answer is found. Higgins recalled:

On reaching Europe, Kelly, still bent on ‘Seeing the Elephant,’ took up his residence at Paris, and there became enamored of a beautiful blonde with a wonderful head of long yellow hair that reached to her heels, and with no morals worth speaking of. In his infatuation he proposed matrimony to the woman and, after settling a round sum in cash upon her, he was accepted and they were married. As the couple were entering a carriage at the door of the church to drive to their rooms a process-server tapped the bridegroom on the shoulder and handed him a court paper, and he was placed under arrest for debt—his wife's debts, contracted before marriage! Of course, he was furious, but he was taken to the debtors' prison and incarcerated, his bride driving away in the carriage her husband had hired to take them to the nuptial chamber. They never met again. . . The artful woman had apparently arranged to have her husband arrested immediately after the marriage, so that she might make off with another of her admirers, and the money Kelly had given her. I never heard what became of Kelly. I fear he died in prison.

Higgins never found out what became of his companion, but apparently Kelly died some 10 years later, 4 March 1872, in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France.

As one of the principal characters in his book The Mystic Spring, Higgins never forgot the well-travelled Irish lawyer. When Higgins returned to Yale many decades later, he was still thinking about him:

As I moved along the road I came to a huge boulder upon which Kelly, the Australian barrister, and I, in the long ago were wont to recline and smoke our pipes, exchanging stories of our earlier life and speculating as to the future. I took a seat on the rock and my mind was soon busy with the past. As I mused it almost seemed as if my old-time acquaintance sat by my side once more . . . I recalled that one pleasant evening in July, 1859, we two boon companions sat on this identical boulder and indulged in day-dreams.

Having scoured the Yale waterfront for the last many decades, I believe I know where this giant rock is. I have comfortably perched atop it myself on many occasions where my own daydreams and historical speculations – the kind that have led to this story – were encouraged. Perhaps particularly so, because it was the main docking point for all those steamboats to Yale that Kelly had dreamed of; to this day, a great substantial iron ring remains embedded in the rock, where shallow-hulled sternwheelers like Kelly envisaged once securely tied.

How is it that stories like this are forgotten? How is it that we know so little of such a prominent transnational gold seeker, and how is it that we seemingly know so little about our foundational experience of a gold rush that, for a moment in time, had so caught the attention of the world and was about to potentially eclipse California?

Kelly’s story and the sternwheeler model of Yale are clues to this extraordinary past. But perhaps it is no surprise that British Columbia has lost so much of its early memory. After all, gold rushes have produced some of the most transient populations to have ever wandered the globe – the largely unknown William Kelly among them.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's last spellbinder also centred around Yale, and the Alexandra Bridge Controversy.

- One of my very favourite Daniel Marshall stories: The remarkable story of ‘Harry’ Collins, the gold rush, and the man who re-connected the Collins family.

- One more Marshall Classic: The tragic story of his great uncle in the Battle for Hill 70.