In my previous column, The Forgotten Context of Canada’s Oldest Chinatown – Part I, we looked at the increasingly discriminatory policies found in California that spurred the Chinese merchant class of San Francisco to purchase the first of 20 lots in Victoria in 1858, which formed the nucleus of Canada’s oldest Chinatown.

Who were some of these Chinese pioneers?

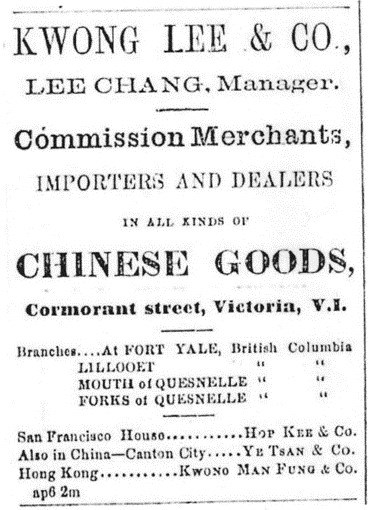

While it is well known that Kwong Lee and Company were established in Victoria in 1858, surprisingly little research has been undertaken to establish their historic connection to other Chinese merchant companies operating in California prior to the Fraser River gold rush.

A collection of documents dating to 1858 have been resting in the British Columbia Archives that provide key evidence, including an exceptional individual who had become the chief spokesperson for the Chinese peoples in San Francisco in their fight for rights against the discriminatory policies and legislation of the Californian government.

From my current research, it appears that Kwong Lee & Company were working as the northern agents for Hop Kee & Company of San Francisco, and the archival trail provides a fascinating collection of documents (financial papers, receipts and so forth) that confirm this. More importantly, as we shall see, are the names of individuals noted on these documents that, in effect, link our 1858 Chinese gold seekers to one of the most prominent and highly regarded members of the early nineteenth-century Chinese Transpacific trade.

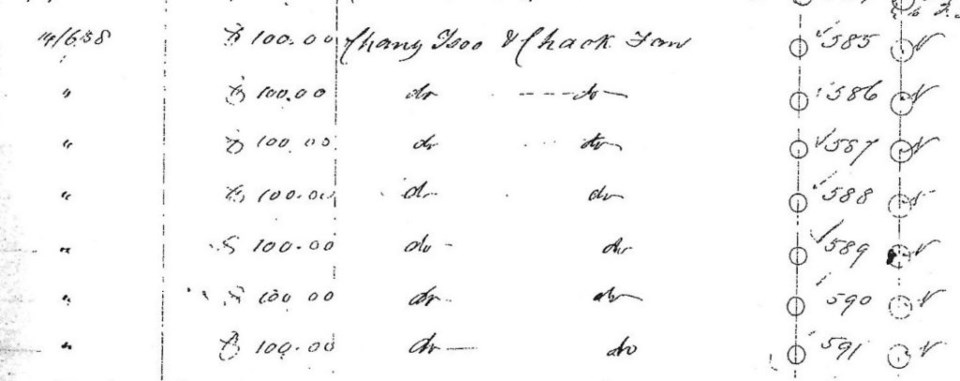

In its archives, the BC Land Titles and Survey Branch holds the original town lot register for Victoria commencing in 1858. It highlights the frenzied rush for real estate that occurred at this time. Every nation of the world is seemingly represented here including the Chinese.

The Sacramento Daily Union of 24 June 1858 reported:

Sam Wo & Co., and Hop Kee & Co., the Chinese merchants, have purchased an entire square for Chinese purposes. No more lots are now sold by the Government; the rush on the land office was so great that it was thought proper to close it.

Chinese were particularly hard hit by the institution of the Californian foreign miners head tax, in addition to being routinely driven from their claims. For example, in 1858, Euro-American miners in Mariposa, California, had ordered Chinese immigrants to leave their community within 48 hours.

Clearly, many were doing so. The San Francisco Bulletin reported, 21 May 1858, that three of the leading “aristocratic” businessmen had left on the Panama for the Fraser River Mines to prospect the country and make further preparations for those who would follow, the newspaper suggesting “that nearly the entire Chinese population . . . will leave for the British Possessions.”

Before BC’s Confederation with Canada (1858-1871), Chinese miners – like all other gold seekers regardless of race – were not forced to pay a foreign “head tax”, but rather had to participate in a universally-applied Crown licensing system. Crown privilege (as instituted in BC) appears in marked contrast to some of the more notorious “individual rights” practiced in California.

It’s worth pointing out that Chief Justice Matthew Baillie Begbie certainly insisted on the admissibility of Chinese testimony in local courts of law, unlike south of the border – making BC a comparative land of both mercantile and individual freedom.

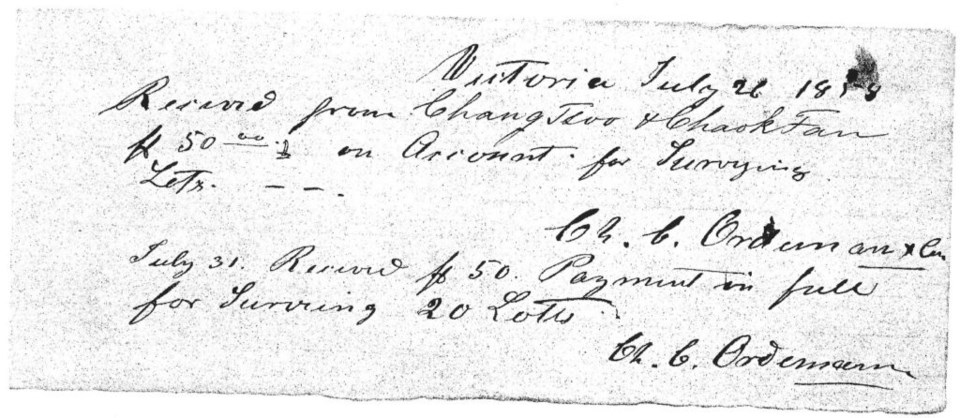

It’s easy to locate the identity of the Chinese representatives from San Francisco in the original Victoria town lot register for 1858. Both Chang Tsoo and Chaok Fan purchased some 20 separate lots, and there seems to be evidence that the Hudson’s Bay Company provided ongoing financing.

In particular, Chang Tsoo is directly associated with Hop Kee and Company of California. Not only was this company protesting discriminatory policies in California, but also the leading mercantile house that established Canada’s oldest Chinatown in Victoria. In my personal conversations with the historian Lily Chow, we are convinced that Kwong Lee was, in fact, a branch of Hop Kee. (For instance, Loo Gee Wing purchased Kwong Lee in 1887, before becoming one of the richest Chinese Vancouverites, had worked for Hop Kee).

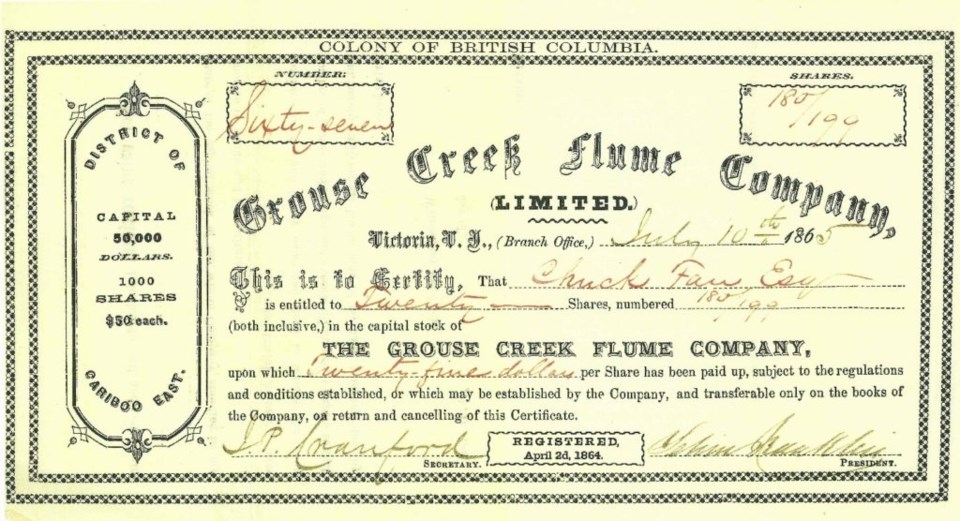

Chaok Fan remained in British Columbia well into the 1860s, as evidenced by his ownership of company stock in the Grouse Creek Flume Company. But it is a third name found on invoicing notes written from Victoria to San Francisco in 1858 that is particularly intriguing: Tong K. Achick.

Along with his two brothers, Tong Achick had been educated at the Morrison Education Society School in Hong Kong in the 1840s. The historian Carl Smith has stated in his book, Chinese Christians: Elites, Middlemen, and the Church in Hong Kong, that the three Tong Brothers “may be considered to be representative of a new class of commercial bourgeoisie that emerged in the China coast cities at the end of the Ch’ing dynasty.”

Smith continues such that “This new class within the Chinese social system was composed of entrepreneurs, business men, financiers, and industrialists. They were the key figures in the industrial and commercial modernization of China following the impact of the west on traditional China.”

The home of the Tong brothers was the village of Tong-ka in the Heung Shan District of Kwangtung Province. In 1839, the oldest of the three brothers, Tong Mow-chee, enrolled in the Morrison School under the name of Achick – becoming one of its very first students.

In the aftermath of the Treaty of Nanking, the British required interpreters for their new consular activities in port cities such as Shanghai. Achick was quickly drafted into the public service; few Chinese people were fluent in English at the time.

By 1847, Achick was appointed Interpreter in the Magistrate’s Court of Hong Kong, before traveling with his uncle to the California gold rush in 1852. As Smith has noted:

The years spent by Tong Mow-chee (A-Chick) in California provided the first opportunity for the Tong brothers to serve the special interests of their countrymen. Although only 24 years of age, A-chick soon became an important leader and spokesman for the Chinese community in California. His English-language education and intimate knowledge of Western ways qualified him for this position.

Achick continued his interpreter’s role while in California, and quickly became a leader of the Chinese community, who made direct representations to the governor of California. Smith quotes the missionary Speer:

This is the individual whose efforts last Spring (1852) in behalf of his countrymen, were the chief means in turning the tide of public opinion in their favour, when those unfriendly to them made the attempt to expel them from the country. And if he remains here, there is no man whose influence will be more felt among the large bodies of emigrants of his own race already in the State, or coming in the spring.

Apparently sometime after 1857, Tong Achick returned to Hong Kong and joined the Chinese customs service – but documents in the BC Archives suggest that he came to Victoria in 1858.

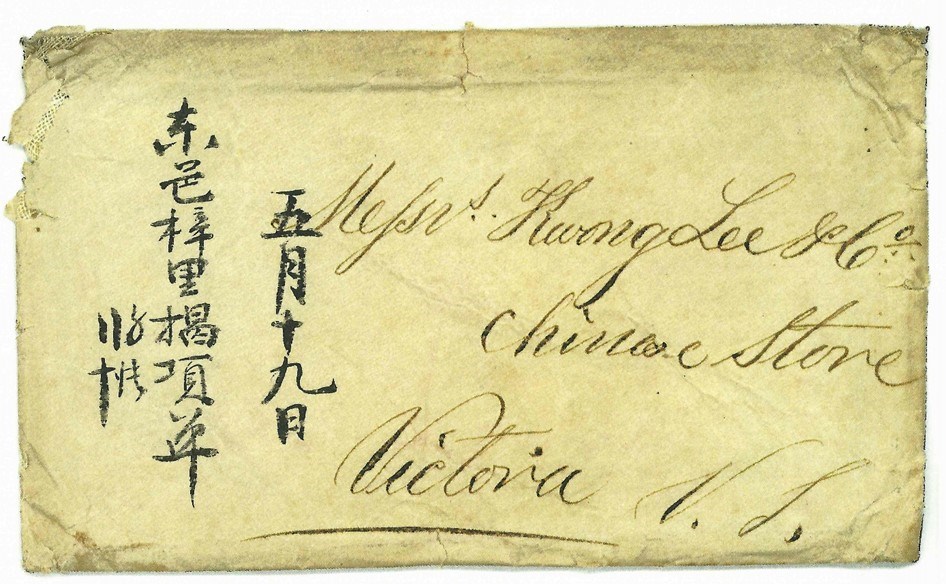

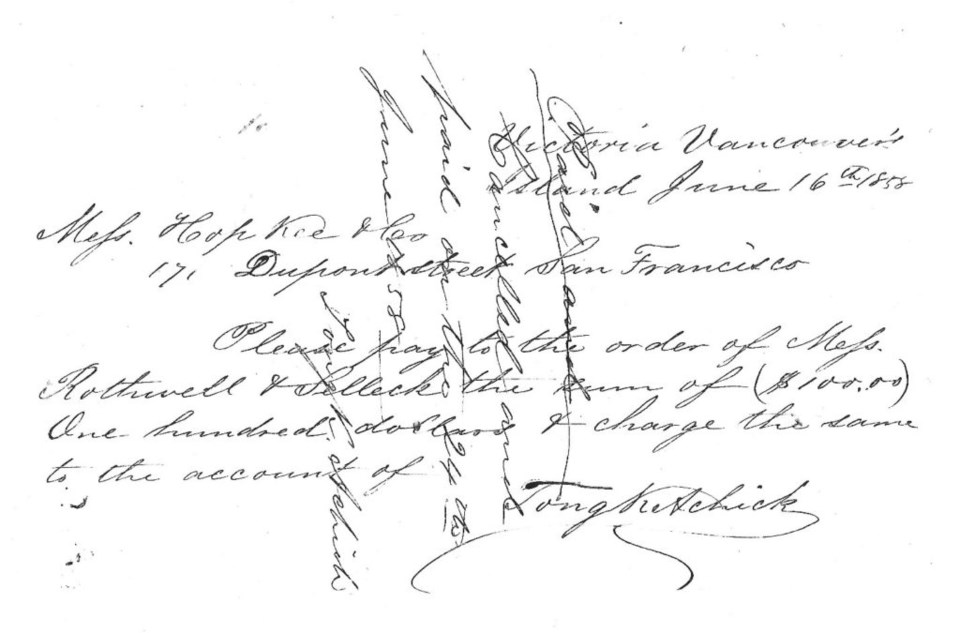

The first document, written in Victoria, 16 June 1858, is an instruction to Hop Kee and Company of San Francisco by Tong K. Achick. Surely, this is one of the “aristocratic” Chinese men noted in the San Francisco press as traveling north to Fraser River.

The next document was written by Chang Tsoo (one of the purchasers of the 20 town lots) while in Victoria, directed to Hop Kee and Co. of San Francisco and subsequently signed off in cross-writing by Achick, 24 June 1858. This suggests that Achick had now returned from Victoria to California.

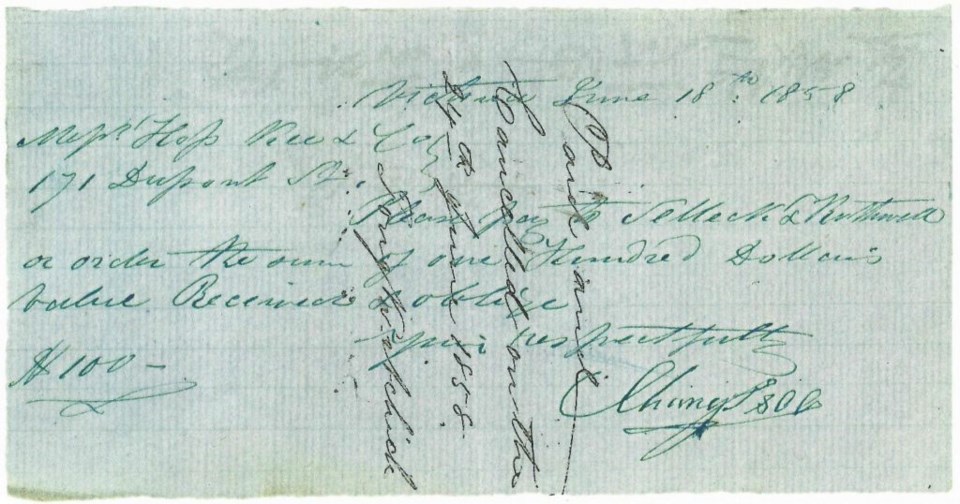

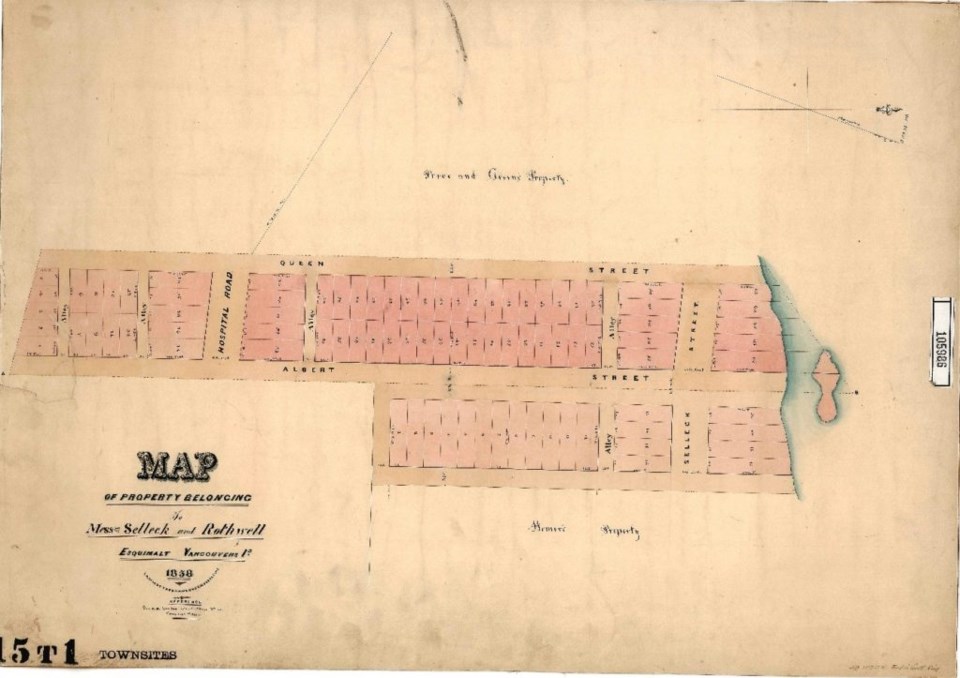

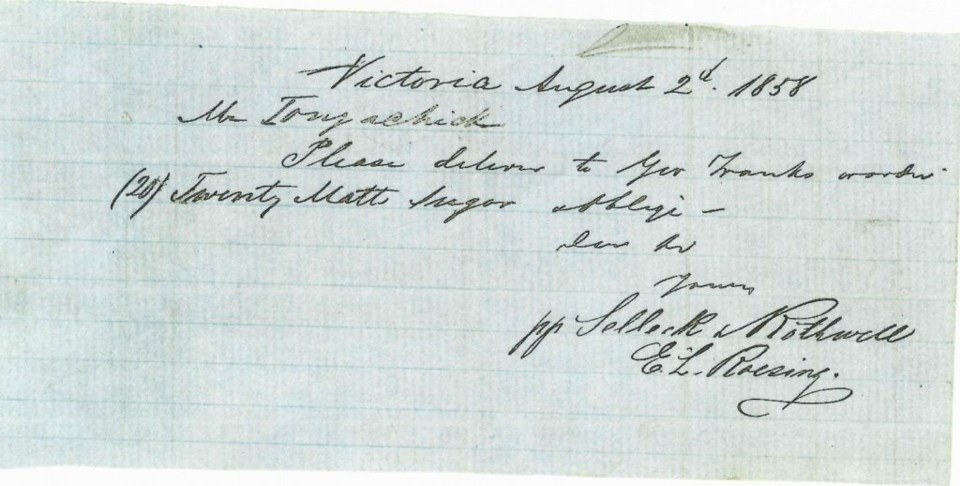

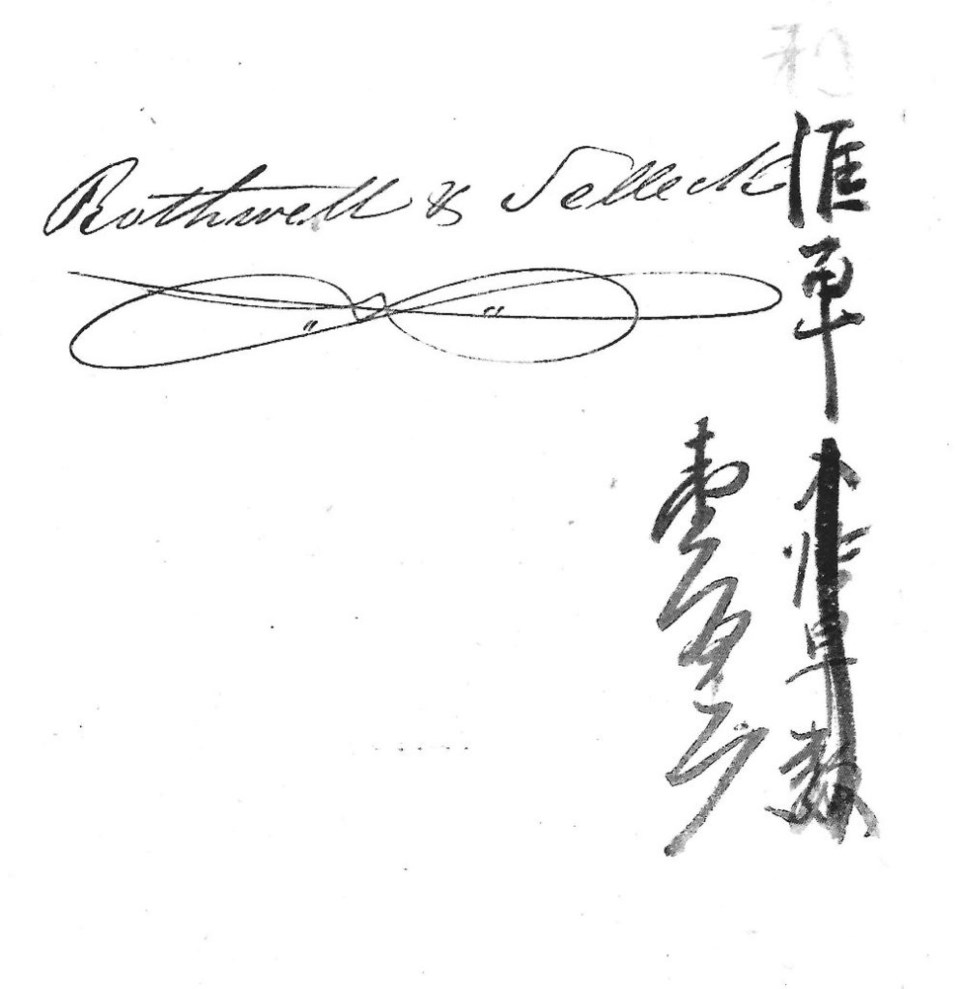

The last document, from August 1858, is a purchase order directed to Tong Achick from merchants Selleck and Rothwell, newly and briefly established in Vancouver Island with large real estate holdings purchased in Esquimalt.

There is a clear connection exhibited here between Tong Achick, Chang Tsoo and Hop Kee and Company and the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 that demands further research.

Clearly, these early Chinese pioneers of the Pacific Slope came not only for gold but also, in the case of British Columbia, a better home.

In many ways, the founding of Victoria’s Chinatown by the California Chinese merchant class – and seemingly led by their key spokesperson, Tong Achick – is very similar to the Hudson’s Bay Company establishing Fort Victoria in advance of American expansion. Both were examples of early business partnerships that sought to work outside the discriminatory practices of the U.S. – it’s no coincidence that the two largest landowners in early Victoria were first and foremost the HBC followed by Chinese. For the British, Vancouver Island was the Gibraltar-like fortress of the North Pacific; for the Chinese in 1858, possibly a new Hong Kong.

After James Douglas retired, the new governor Arthur Kennedy received a memorial in 1864 from Victoria’s Chinese merchants that speaks directly to the kind of persecution they escaped from in California. Reported in the British Colonist, 5 April 1864, it stated:

Chinese Address to Gov. Kennedy

In the reign of Tong Chee, 3rd year 2nd month, 26th day.

Vancouver Island, 1864 year, 4th month 2d day.

Us Chinese men greeting Thee Excellency in first degree Arthur Edward Kennedy . . . . All us here be dwellers at Victoria, this Island, and British Columbia, much wish to shew mind of dutiful loyalty to this Kingdom Mother Queen Victoria, for much square and equal Kingdom rule of us.

Just now most humbly offer much joined minds of compliments to Thee Excellency Governor Kennedy, on stepping to this land of Vancouver, that thee be no longer in danger of Typhoon, us much delighted. Us be here from 1858, and count over two thousand Chinese.

Chinese countrymen much like that so few of us have been chastised for breaking Kingdom rule.

This Kingdom rule very different from China. Chinese mind feel much devoted to Victoria Queen, for the protection and distributive rule of him Excellency old Governor Sir James Douglas, so reverse California ruling when applied to us Chinese country men. Us believe success will come in obeying rulers, not breaking links, holding on to what is right and true.

In trading hope is good and look out large; big prospects for time to come.

Us like this no charge place, see it will grow higher to highest; can see a Canton will be in Victoria of this Pacific.

The maritime enterprises will add up wonderfully and come quick. China has silks, tea, rice, sugar, &c. Here is lumber, coal, and minerals, in return, and fish an exhaustless supply, which no other land can surpass.

In ending, us confident in gracious hope in thee, first degree and first rank, and first link, and trust our Californian neighbors may not exercise prejudice to our grief.

Us merchants in Chinese goods in Victoria mark our names in behalf of us and Chinese countrymen. Wishing good luck and prosperity to all ranks, and will continue to be faithful and true.

Us Chinese men much pleased Excellency continue to give us favor always. Us remember to thee.

Signed

Tai Soong & Co., by Tong Kee Yan,

Woo Sang & Co., by Chang Tsoo

Kwong Lee & Co., by Lee Chang, Tong Fat.

Upon having received this address by a Mr. Hall who served as translator, he subsequently introduced the Chinese delegation to Governor Kennedy (later governor of Hong Kong, 1872–77) who replied through Lee Chang who interpreted the Governor’s words. The Colonist reported:

[T]hat he was very happy to receive their address. It was the desire of her Gracious Majesty the Queen and the Imperial Government to render equal justice to people of every nationality in her dominions, and he assured them that the Chinese population in this colony would be protected in their lives and property as well as any other of her subjects. His Excellency said he thought very highly of the sentiments expressed in their address, and said they showed a great knowledge of trade and commercial principles. He hoped they would also show the community that they would not be wanting in obedience to the laws, and they might depend on always receiving the protection of the laws.

His Excellency then asked several questions in regard to the Chinese population of this and the neighboring colony, which were intelligently answered by Lee Chang, who stated that there were about 2,000 Chinamen in the two colonies, of whom some 300 or 400 were in Vancouver Island. Those in British Columbia were chiefly employed in mining.

His Excellency remarked that he had always found the Chinese an orderly and industrious people, and he hoped they would keep up the same good reputation in this colony. He then courteously dismissed the deputation.

So, here we see quite plainly that James Douglas had “reversed” the California policies of prejudice and intolerance and this fits well with the governor’s own views in the matter. Seen from this contextual perspective, I believe the words of Douglas written in 1858 must be given substantially greater credence. He declared:

‘I am glad that Her Majesty’s Government . . . generously grants, within the Colony of Vancouver’s Island, a refuge for political exiles,’ wrote the governor, ‘provided they yield obedience to the Laws, and avoid public scandals, and lead quiet and honest lives.’

The attraction of British Columbia was gold, but for those outside full American citizenship, BC represented much more than the potential for economic gain. In the case of the Chinese, it was a rush not only for gold, but freedom itself.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.