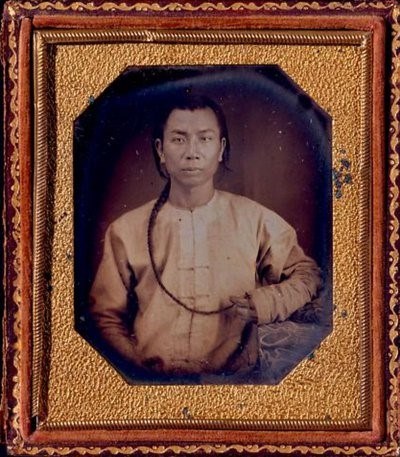

A couple of months ago, sitting at the bar of the Bent Mast Pub in Victoria, I met a recent arrival to our city who had relocated from California. What started as a casual conversation led me to comb my personal archives of historical notes and documents; this gentleman’s relocation to Victoria was motivated solely for the memory and love of his mother who had been born here – the Lee family. As we discussed his story further, I found out his ancestors had come to Victoria at the height of the 1858 Fraser River gold rush and the founding of Canada’s oldest Chinatown.

Serendipity had struck again, here we were – two descendants of the gold rush – in a chance meeting, one of Chinese origin, the other Cornish!

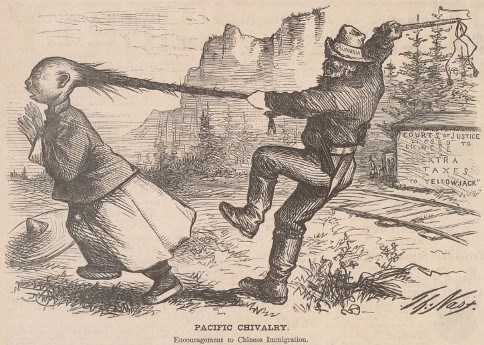

I have always been interested to further explore the beginnings of the Chinese presence at Fort Victoria. In my opinion, current history writings have not sufficiently pursued the connection to San Francisco of these early Chinese who moved up the Pacific Slope. The Chinese peoples of California, like their Black and Hispanic counterparts, were increasingly discriminated against by the exclusionary legislation and practices of California gold rush society. As the Californian Historian John Hittell wrote in the early 1860s of the “Anti-Chinese Mob”:

The white miners have a great dislike to Chinamen, who are frequently driven away from their claims, and expelled from districts by mobs. In such cases the officers of the law do not ordinarily interfere, and no matter how much the unfortunate yellow men may be beaten or despoiled, the law does not attempt to restore them to their rights or avenge their wrongs.

Just three years before the BC gold rush in 1855, Chinese merchants based in San Francisco made an appeal to the American public, asking that their rights be respected.

Recorded in the Sacramento Daily Union, 12 September 1855, “The Appeal of the Chinese Merchants” stated:

TO THE AMERICAN CITIZENS. – Americans: We, the undersigned, Chinese merchants, come before you to plead our cause, and that of our countrymen, residents of San Francisco, or diffused throughout California.

We come to ask for the moral and industrious of our race liberty to remain in this State, and to continue peaceably and without molestation in our various labors and pursuits. . . Neither injustice nor severity has been spared us. . . Instead of the equality and protection which seemed to be promised by the laws of a great nation to those who seek a shelter under its flag, an asylum upon its territory, we find only inequality and oppression.

Frequently before the Courts of Justice, where our evidence is not even listened to – where, if it obtain a hearing, by favor, but rarely is any account made of it. Inequality before public opinion – which is so far, apparently, from considering us as men, that many of your countrymen feel no scruple in making our lives their sport, and in using us as the object of their cruel amusement. Oppression by the Law, which subjects us to exorbitant taxes imposed upon us exclusively – oppression without the pale of the law, which refuses us its protection, and leaves us a prey to vexations and humilities, which it seems to invoke upon our heads by placing us in an exceptional position.

Believe us, we have exaggerated nothing in this picture. . . . We see well that you appear to desire our departure . . . [but] can they, at a given moment, provide themselves with the means of quitting this country in a body, in order to seek elsewhere some less inhospitable land?

It has been stated that the 1855 session of the California Legislature “was perhaps the high-water mark of anti-Chinese sentiment” for the whole of the 1850s, and a more than compelling reason to relocate to the New El Dorado of the north.

Hittell wrote of the California Chinese merchant class that “nearly all of them are members of five great companies, called the Yung-Wo, the Sze-yap, the Sam-yap, the Yan-wo, and Ning-yeung companies” and that in San Francisco “the merchants are usually in partnerships, with not less than three nor more than ten partners; all of whom live in the store, and deal chiefly in Chinese silks, teas, rice, and dried fish.”

Two of the many Chinese companies that were apparent signatories to this 1855 petition were those of Sam Wo and Hop Kee. Just three years later in 1858, Hop Kee & Company had contracted Allan, Lowe & Company (Governor James Douglas’ favoured merchant house in San Francisco) to transport 300 Chinese peoples to Victoria – the original copy of this document exists in the BC Archives collections. These early Chinese pioneers to British Columbia were likely laborers working under contract. As Hittell has noted:

The common laborers are brought to the state under contract to work for several years at a low rate of wages (from four to eight dollars) per month; and they usually keep these contracts faithfully. The employers in these cases are either the companies or associations of Chinese capitalists. The Chinamen generally are very industrious; indeed they are the most industrious class of our population, and also the most humble, quiet, and peaceful. The merchants are considered to be very faithful to their promises, and in San Francisco they can get credit among their acquaintances quite as readily as other men in similar branches of business.

As historian John Adams has noted, it is likely that just as “Captain Jeremiah Nagle of the SS Commodore had discussed the plight of the blacks in California with James Douglas during the early spring of 1858 when discrimination there was at a peak” (resulting in Douglas’ invitation to blacks “to settle under the freedom of the British flag”), a similar invitation would have been extended to the persecuted Chinese peoples of California.

This is not surprising, considering that Douglas was himself a mixed-race, Scotch-West Indian who had experienced firsthand the growing racist, exclusionary policies adopted in Old Oregon.

By 1862, Oregon adopted a law that required all blacks, Chinese, Hawaiians, and Mulattos residing in the state to pay an annual tax of five dollars, while black/white intermarriage was banned. This prohibition was subsequently extended in 1866 to anyone who was ¼ or more Chinese or Hawaiian, and ½ or more Indigenous.

In this sense, Oregon was very much like California. Hittell, again writing in the early 1860s, recorded the similar exclusionary laws under the title of the “Inferiority of Colored Persons”:

All white male citizens are equal before the law of California; but negroes, Indians and Chinamen are not permitted to vote or to testify in the courts against white men. In a criminal case, one-eighth negro blood and one-half of Indian blood, in civil cases one-half of either, disqualifies a witness for testifying against a white man.

To my mind, when placed in this context, Douglas’ offer of equality under the law for all – which had become Imperial policy – becomes more than understandable, and a unique welcome for the times extended to Chinese people, too.

As a consequence, starting in 1858, members of the Chinese merchant class of San Francisco took the necessary steps to purchase the first of 20 town lots in Victoria that formed the nucleus of what is still the oldest Chinatown in Canada.

Who were some of these Chinese pioneers? One, in particular, was the most prominent representative of the Chinese communities in the Golden State – another great untold story. That’s the subject of Part II of this history I recently tracked down, thanks in part to a pint of beer with a descendant of these early Chinese pioneers to Victoria.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.