It seems to me that having researched the history of our province for many decades, the establishment of British Columbia was born of the clouded realities of a colonial project mired in the chaos of a frontier gold rush.

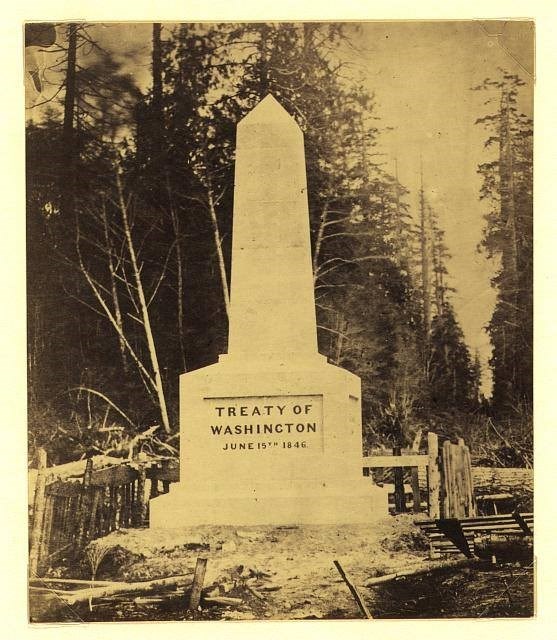

“This colony was not like Australia or New Zealand,” warned the Duke of Newcastle. He was right. As I have stated in a previous article, the establishment of BC did not fit formal models of colonialism practiced elsewhere in the British Empire. This was entirely due to the chaos and warfare that crossed the unmarked border with the United States – the partition line that cut Old Oregon in half in 1846.

From my own research on Indigenous-newcomer conflict in the Northern Pacific Slope region and particularly British Columbia, the central preoccupation of Governor James Douglas was the ever-constant threat of Indigenous warfare on fledgling non-native settlements. This was the main concern of the imperial government, too.

Herman Merivale, the permanent undersecretary of state for the colonies, wrote (while professor of Political Economy at Oxford University) that:

The history of the European settlements in America, Africa, and Australia presents everywhere the same general features – a wide and sweeping destruction of native races by the uncontrolled violence of individuals, if not of colonial authorities, followed by tardy attempts on the part of governments to repair the acknowledged crime.

This threat of Indigenous-newcomer violence and warfare is a recurrent theme found throughout the early history of the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, and most certainly south of the 49th parallel in Washington Territory.

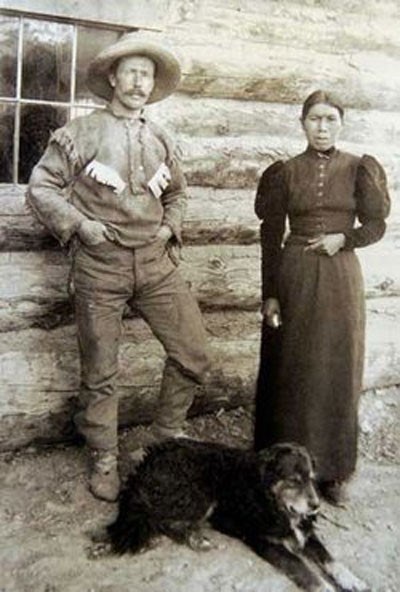

As such, Douglas – either in his capacity as Chief Factor of the Columbia Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) or as a colonial governor – was always careful to enact policies that ensured peaceful relations with Indigenous peoples. Predicated in large measure on earlier and successful fur trade/HBC practices (negotiated for the most part within pre-existing Indigenous systems of law), his policies largely stemmed violent conflict until the critical and catastrophic year of 1858, when the mainland Crown Colony of British Columbia was formed.

Douglas had repeatedly warned the imperial government that violent conflict would likely occur with the expansion of the California mining frontier into British (let alone Indigenous) territory. The partition of Old Oregon in 1846 had still not been fully surveyed, and remained, as the Duke of Newcastle considered, “an imaginary boundary” that neither defined the Indigenous world nor the violent warfare directed largely from south of the border.

Douglas had already witnessed the violent confrontations increasingly occurring in Washington territory prior to 1858, where the “Indian Wars” continued well into the 1870s, considered the last great such conflicts in the United States.

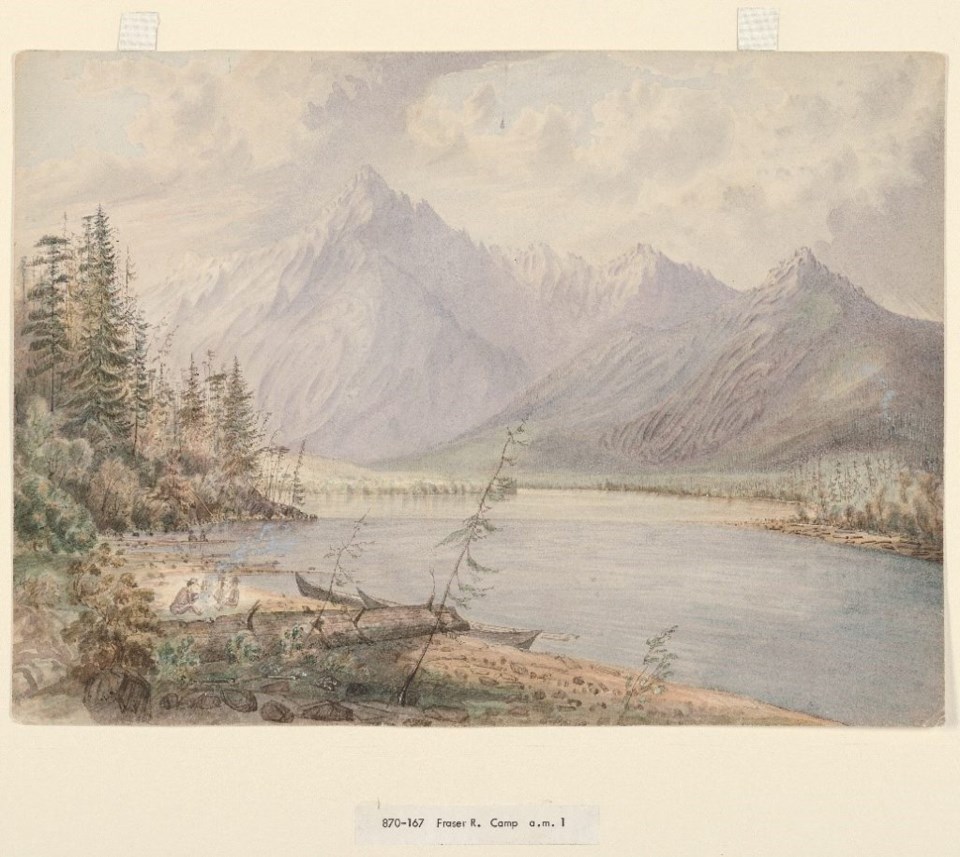

In the summer of 1858, as Douglas had predicted, wholesale conflict erupted along the Fraser and Thompson river corridors.

It was due to the huge influx of non-native gold seekers that precipitated the Fraser River War of that year – a largely-forgotten event that has taken 160 years to tell more fully.

Indigenous lands along the southern section of the Fraser River corridor below the 51st parallel were invaded by large paramilitary-like companies of foreign miners. The extermination practices of the California mining frontier was baggage carried north with the requisite pick, pan, and shovel. Mining – the single greatest disruptor of Indigenous lands in the American West – created a frontier defined and segregated by race. This frontier did not recognize the British-American border, and effectively shaped the Fraser River landscape in its own image.

This sudden invasion broke the back of Indigenous control over access and use of their territories and resources, shaped the Native landscape into a series of foreign, ethnically-defined mining enclaves, and precipitated the formation of Indian reserves even before the British proclaimed the Crown Colony of BC in the fall of 1858.

Among the Indigenous Nations that bore the brunt of the expansion of the California mining frontier into BC were the Nlaka’pamux, Okanagan, and the Secwepemc (Shuswap) peoples – who were in the process of forming a confederacy to drive out all foreign born gold seekers.

Ethnographer James Teit recounted some forty years later the dire circumstances of this war and the Indigenous response to it:

Hundreds of warriors from all parts of the upper Thompson country had assembled at Lytton with the intention of blocking the progress of the whites beyond that point [he stated], and, if possible, of driving them back down the river. The Okanagan had sent word, promising aid, and it was expected that the Shuswap would also render help. In fact the Bonaparte, Savona, and Kamloops bands had initiated their desire to assist if war was declared. For a number of days there was much excitement at Lytton, and many fiery speeches were made. CuxcuxesqEt, the Lytton war-chief, a large, active man of great courage, talked incessantly for war. He put on his headdress of eagle feathers, and, painted, decked and armed for battle, advised the people to drive out the whites.

In 1859, the next year after the conclusion of the Fraser River War, Douglas remained concerned about the possibility of “having the Native Indian Tribes arrayed in vindictive warfare against the white settlements.” In further reporting to Lord Lytton, Secretary of State for the Colonies, Douglas – from his long years of experience – cautioned the importance of maintaining peaceful relations:

As friends and Allies the native races are capable of rendering the most valuable assistance to the Colony while their enmity would entail on the settlers, a greater amount of wretchedness and physical suffering, and more seriously retard the growth and material development of the Colony, than any other calamity to which, in the ordinary course of events, it would be exposed.

Douglas understood this threat well. Without the active participation of Indigenous peoples in the fur trade, HBC operations on the Pacific would have been severely hampered – if not entirely impossible.

While the gold rush of 1858 seemingly changed everything – having eclipsed the fur trade – the new economy was still ultimately dependent in large measure on the involvement of Indigenous peoples.

“Take away the Indians from New Westminster, Lillooet, Lytton, Clinton,” stated MLA Thomas B. Humphreys during the Confederation debates just 12 years later, “and these towns would be nowhere. . . Take away this trade and the towns must sink. I say, send them out to reservations and you destroy trade, and if the Indians are driven out we had all best go too.”

Douglas’ repeated warnings to the imperial government about the likelihood of native-newcomer conflict were recorded in colonial dispatches that, in many instances, were printed for British Parliament. These published warnings were subsequently viewed by the influential Aborigines Protection Society (APS) – borne of William Wilberforce’s anti-slavery movement – who in short order expressed great concern to the Colonial Office that exterminationist campaigns against Indigenous peoples in California was about to be repeated. They urged immediate action. As such, Lord Lytton demanded that all necessary steps be taken to protect the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia from a similar fate and sent the APS letter to Douglas on 2 September 1858:

It appears, from all the sources of information open to us, that unless wise and vigorous measures be adopted by the representatives of the British Government in that Colony, the present danger of a collision between the setters and the natives will soon ripen into a deadly war of races, which could not fail to terminate, as similar wars have done on the American continent, in the extermination of the red man.

The danger of collision springs from various causes. In the first place, it would appear from Governor Douglas’s Despatches, as well as from more recent accounts, that the natives generally entertain ineradicable feelings of hostility towards the Americans, who are now pouring into Fraser and Thompson Rivers by thousands, and who will probably value Indian life there as cheaply as they have, unfortunately, done in California.

The APS and indeed British policy sought to stem the violent tide of the California mining frontier and encouraged “some guarantee that the promised equality of the races should be realized . . . . and instead of obstructing the work of colonization they [indigenous peoples] might be made useful agents in peopling the wilderness with prosperous and civilized communities, of which they one day might form a part.”

In my opinion, the APS letter sent by Lytton to Douglas provided the new governor with the essential spirit of the Indigenous protection policy that had evolved. Indigenous peoples were to be treated as equals, and the method to secure this goal – from the imperial perspective – was to ensure that land reserves were set aside and protected from newcomer encroachment.

These Anticipatory Reserves, as Douglas had called them, were for the express purpose of forestalling further conflict, a safe refuge in which to prepare Indigenous peoples for entry into the “civilized life.”

From our modern perspective, these policies that had Liberal humanitarianism as their foundation appear as solidly Eurocentric and self-justifying, but nevertheless a concerted attempt to halt the exterminationist practices found throughout the world in previous centuries, and particularly the atrocious results of U.S. cultural assumptions still prominent during the 19th century.

Check back next week for Part Two.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- In the mood for a film? No worries. Check out Daniel Marshall's Shaw Cable presentation on B.C.'s formative years.

- Mike Robinson on a whale of a shift in seasons on the west coast.

- Cathy Converse on one of the most remarkable women in the history of B.C. - or indeed, anywhere - Agnes Dean Cameron.