Some of history’s most crucial turning points have since fallen from public imagination.

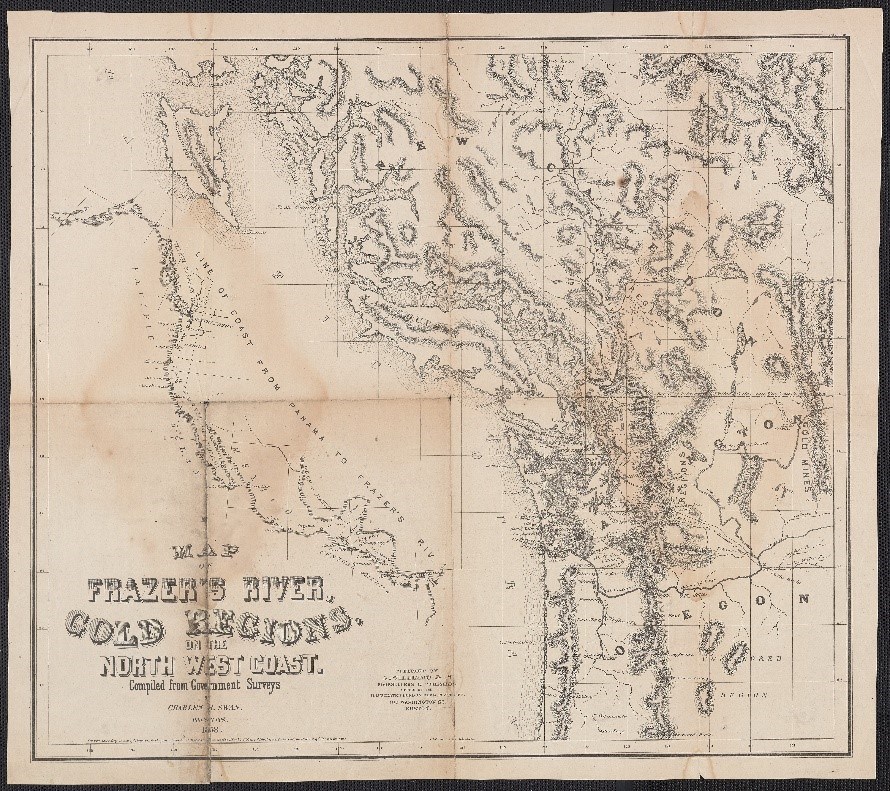

We’ve talked about the history of the Fraser River War, but equally important – and forgotten – was the application of an imperial “land disposal” policy the Colonial Office was unsure how to apply to the peculiar circumstances of British Columbia.

This was in large measure due to the unknown and chaotic conditions of the Fraser gold rush, and failed land policies practiced elsewhere in the British Empire. In my previous column, I noted that if the U.S. had instituted a land policy in Washington Territory based on a preemption system, why would BC not have also followed suit immediately?

Almost two years would unfold before preemption as a means of Crown land disposal would be enacted in British Columbia, and this delay was due to internal debate within the Colonial Office. This internal debate was very much evident in communications between the Colonial Office and the Imperial Emigration Board.

The Duke of Newcastle (who succeeded Lord Lytton as secretary of state for colonies), had increasingly seen the dilemma of British Columbia. But before consenting to Governor James Douglas’ anxious request to institute a preemption system, Newcastle required further in-house expert opinion.

One such person was Thomas W. C. Murdoch, Chairman of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission. Writing to Herman Merivale of the Colonial Office, 23 September 1859, Murdoch was adamantly opposed to the institution of a preemption system in British Columbia:

It appears to me that nothing but the clearest necessity should induce the Government to have recourse to such an arrangement. It may perhaps be unobjectionable in the case of isolated adventurers in tracts of Country far removed from actual settlement, and where no other rights have grown up or are likely to be immediately created. But in a Country like British Columbia and as a means of meeting the demands of a large body of settlers it could not fail to introduce great confusion and uncertainty of title and lay the ground for future disputes and litigation.

From the nature of the case there would be no definition of the boundaries of individual settlers, and it is impossible to believe that under such circumstances rival claims to the same land would not continually spring up. And in a Country where superficial improvements are so easily made and as easily obliterated, the decision of such claims would involve very great difficulty; not only to the Executive Government, who would first be called upon to decide them, but even to Courts of Law.

The History of every new Colony shows the embarrassment and loss which has arisen from a careless or indiscreet system of disposal of the Crown Lands in the first instance. . . This was the case in Ceylon and Natal where land was granted with great laxity and without reference to any General survey, and the records of the Colonial Office contain ample proof of the confusion and expense which has been caused in Ceylon. . . .

Upon the whole I would recommend that no countenance should be given to Governor Douglas’ proposal to sanction the occupation with preemptive rights of unsurveyed land.

Murdoch’s lengthy assessment was next reviewed by Arthur Blackwood, the Colonial Office’s senior North American specialist. He openly wondered whether the unique circumstances of British Columbia would call for a strict application of land policies practiced elsewhere. Blackwood wrote:

The Commrs opinion [Murdoch] is that it will be more advantageous for the Colony in the end not to sanction Governor Douglas’ plan of holding Land under a preemptive right, even though that plan be temporary.

But has he sufficiently adverted to the consideration (which the Duke of Newcastle entertains) that the vicinity of the Americans makes it almost impossible to maintain the system of disposing of Land in the Colonies which is so easily indoctrinated at Whitehall. Home views on this point are sometimes carried to excess – irritate the Colonists – and retard the success of a settlement. . .

It will deserve Consideration which plan to adopt – whether to insist on the rigorous adherence to principles which, though sound in themselves, are not applicable in all cases, or to sanction a departure from them under the peculiar circumstances of British Columbia.

Herman Merivale seemingly agreed with Blackwood, particularly as the United States had already instituted a preemption system that continued to offer new settlers a substantially more attractive land disposal policy. It would be British Columbia’s potential undoing if the imperial government continued to demand formal and expensive surveys before country lands could be settled. Merivale stated:

Nothing can be sounder than Mr. Murdoch’s reasoning, but how are we to exclude squatters in Brit. Columbia, when in Oregon, on the other side of an imaginary line, every man (as I understand the case) can select 160 acres of Country land where he pleases with a certainty of never being disturbed until the Government Surveyor reaches him, perhaps years afterward, & perhaps the prospect of not having to pay even then?

This was the peculiar circumstance of British Columbia. With each subsequent review of the Murdoch report, the Colonial Office was increasingly of the opinion that the preemption system advocated by Douglas should be sanctioned, and the governor “instructed to press on surveys, even of a rough kind, as rapidly as possible” to expedite immediate settlement.

In the race to compete with the United States, Douglas continued to wait – likely with impatience – for Britain to confirm his final plan. Newcastle, though largely in agreement, remained concerned that potential American settlers would quickly take the best of B.C.’s lands:

I am very unwilling to set aside the opinion of Mr. Murdoch on such a Matter as this – especially when I cannot hesitate to admit the soundness (in theory) of his arguments. I believe however that two such opposite systems as the English and American cannot co exist on two sides of an imaginary boundary, and it is certain that the U.S. Citizens will not adopt ours. It must not moreover be forgotten that in such a Colony as B.C. population is wealth, and every new Settler will soon add much more to the Revenue than it will lose by diminution (for a time) of Land Sales.

In the end, needing to get settlers on the ground even without formally completed surveys, Douglas waited no longer. As in previous occasions, he acted unilaterally in advance of receiving final approval, and proclaimed the Preemption Act of 1860.

The Emigration Office was dismayed, immediately expressing regret and disapproval:

We, therefore, think it a matter for regret that Governor Douglas should have adopted the course he now reports. Without denying that under the peculiar circumstances of British Columbia, it may be more important not to discourage persons disposed to settle on the Land, then to maintain strictly the rule which forbids the sale or grant of unsurveyed Crown Land, we think that the relaxation of that rule should have been restricted to the absolute necessity of the case, and should not have been made general with the view to invite Settlers. Probably the effect will not be sufficiently extensive to create any very serious difficulty, but we would suggest that Governor Douglas should be recommended to withdraw the general Instructions which he has issued and should not sanction the grant of unsurveyed Land on preemptive right except on special application.

While members of the Land and Emigration Commission urged that Douglas withdraw his ordinance, the Colonial Office disagreed. T. Frederick Elliot, Assistant Under-Secretary stated in response:

This the Com[missione]rs regret, but their views on the subject in their former report were not adopted at this Office, and therefore this regret cannot be expressed to the Governor. It was intended, if I understand aright, to leave him a wider discretion to meet the pressure for lands in the best way he could, and I presume that under that view of the case his proceeding will be tacitly acquiesced in by way of experiment.

Did Douglas ever know that his plan to meet the chaos of the gold rush received such opposition? Difficult to say, but this was very much an experiment that reflected all the uncertainties of a frontier gold rush where Douglas’ policies and practices did not fit any formal models of land management found elsewhere in the empire.

The wait-and-see, provisional nature of the colony and the governorship were reflected in Douglas’ temporary Crown land policies and the wide discretionary powers he held. The provisional nature of these policies was particularly evident with the institution of the Anticipatory Reserve system – the very flip side of the preemption system instituted – which used rough surveys, as opposed to formally surveyed boundaries, hastily allotted for one main and immediate purpose: to forestall non-native preemption of native lands earmarked for protection, which is to say, to forestall any possibility of native-newcomer warfare again erupting.

The Anticipatory Reserve system did just that. It anticipated the potential for grievances over the paucity of highly-prized, agriculturally-rich lands that constitute today only about 3% of the entire province, but it has also left a legacy of disputes – particularly with regard to the formation of these early Indian reserves. Was it worth it?

The Hudson’s Bay Company knew the trail that connected BC with Fort Vancouver (on the lower Columbia River near Portland, Oregon), was no longer about annual HBC fur brigades from New Caledonia, but had the potential to convey thousands of newcomers in search of arable land.

James Douglas also knew this. Not only had he rightly predicted the 1858 conflict during the Fraser River gold rush – in which thousands of foreign gold seekers travelled through the Okanagan and Shuswap valleys, in many cases setting off conflict – but with the introduction of the American-style system of land preemption in 1860, Douglas well knew that conflict over land was inevitable and it could easily cross the border again.

It is this mentality that needs to be fully understood.

As difficult a proposition as this may seem in 2019 – Douglas was most concerned about a pronounced cultural mindset that existed south of the border that included an exterminationist attitude with respect to Indigenous peoples.

This did not end with the Fraser River War of 1858, but was prevalent throughout the governorship of Douglas. By way of example, a “Special Dispatch to the Colonist” newspaper in Victoria, dated 24 October 1865 – reported:

A special order has been issued from headquarters for the re-arrest of Captain John Hill, of the 6th infantry, C[alifornia] V[olunteers], who is on trial before a military court martial on a charge of murder, alleged to have been committed in Nevada. . . It is charged that when his company were on their way through Nevada they found the dead body of an Indian woman with a living child clinging to it. Hill ordered the dead woman to be scalped and not satisfied with this cold blooded act, ordered the infant to be torn from the bosom of its dead mother and dashed over a precipice. The fall not completely killing the child, its brains were dashed out with stones by orders of Capt. Hill.

Today, this is foreign, distant and utterly repugnant – but this was a common story in Douglas’ day; common enough to cause the Aborigines Protection Society of London to lobby the British government and demand protection for the indigenous peoples of British Columbia.

This is what Douglas had sought to prevent, and what he contended with throughout his governorship.

This policy was also a response to any confusion potentially caused by a lack of formal surveys, so as not to risk the colony’s fiscal insolvency. While the Colonial Office had expressed fears about land policies that could lead to later confusion, expensive litigation – or block settler progress – Douglas’ remedy was to have signs and corner posts roughly marking out the potential Indian reserve that would not be formalized until a later date.

Let’s remember, the cost of the formal survey process simply could not be undertaken at this time. Therefore, this policy anticipated the potential for both reserves and non-native settlement while striving to avert conflict – and operated within the seemingly contradictory poles of Queen Victoria’s goals of protection and progress.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.