In Part I, we saw that Canada, in negotiating BC’s union into Confederation, had effectively ignored difficult questions that might impede immediate political union, specifically Article 7 (Canadian system of tariffs), Article 11 (the transcontinental railway), and Article 13 (federal responsibility for Indigenous peoples).

I have written previously about how the Canadian system of tariffs was the most contentious issue, by far, that concerned members of the BC colonial legislature.

The BC Tariff policy was favoured by many as it provided more protection for agricultural and business interests who feared being inundated by cheaper Californian imports. These fears were exemplified in the minutes of the “Debate on the Subject of Confederation with Canada.” Extensive debate on this issue alone raised tariffs to equal, if not greater, status than the most-scrutinized demands for the introduction of responsible government and a transcontinental rail link with Canada. And yet Article 7 (Tariffs) stated that the old BC Tariff should:

continue in force in British Columbia until the railway from the Pacific Coast and system of railways in Canada are connected unless the Legislature of British Columbia should sooner decide to accept the Tariff and Excise Laws of Canada.

Article 7 effectively postponed any decision on modified tariffs; Canadian negotiators realized the immediate introduction of their policy would have seriously jeopardized BC’s entry, and Canada’s expansionist ambitions. For Canada’s immediate purposes, BC policy was allowed to stand, though at odds with the Canadian position. Harmonization would have to wait.

In the case of Article 11, the Canadian government committed itself to the construction of a transcontinental rail link. Prior to confederation, the people of Victoria had petitioned Governor Anthony Musgrave that Vancouver Island should not be left out of any future plans for a cross-country rail line. After a motion proposed by Dr. John Helmcken, an eight-to-two vote of the colonial legislative council, 10 February 1871, reaffirmed the desire for some kind of Island connection with Canada.

And yet, in the same way that Article 7 had left tariffs an open question, Article 11 would not specify the rail route through BC, nor the location of a Western terminus. The railway clause read in part:

The Government of the Dominion undertake to secure the commencement simultaneously, within two years from the date of Union, of the construction of a Railway from the Pacific towards the Rocky Mountains, and from such points as may be selected, east of the Rocky Mountains, towards the Pacific to connect the seaboard of British Columbia with the Railway system of Canada; and further, to secure the completion of such Railway within ten years from the date of Union.

As with the tariff clause, the Terms of Union were written so that final decisions on divisive issues were effectively postponed. If the Canadian government had demanded that BC accept the Canadian tariff immediately, or set an exact location for a western terminus, it is unlikely that BC’s decision to join Canada would have occurred so quickly – if at all.

In the case of the railway clause, Article 11 allowed all regions of the “United Colony” (Vancouver Island and BC merged in 1866) to believe they were destined for commercial greatness as profits from railway surveys and ultimate construction were assured to all regions by various representatives of Canada.

As a result, BC politicians divided into self-interested camps. Many potential rail corridors were projected in an elaborate federal survey program that seemed to have no end in sight. Through it all, the Canadian government exacerbated old divisions of “Island versus Mainland” – once two separate colonies – that flared up over whether the Western rail terminus would end at either Esquimalt or Burrard Inlet, respectively.

Obviously, Canada ultimately chose to bring the railway down the Fraser River. (Contrary to current historical thought, the Bute Inlet Route favoured by Vancouver Island was deemed a practicable route – surely another great untold story.)

“The Terms, the full terms, and nothing but the Terms” was the rallying cry as Islanders, in particular, rightly viewed that the BC Terms of Union had been breached by the Canadian government.

Finally, consider Article 13 – federal responsibility for Indigenous peoples. Once again, it postponed (again!) any immediate harmonization of two distinctly different native land management policies. Much like Article 7 established BC could not dictate changes to the Canadian tariff structure, Article 13 enshrined a similar relinquishment of BC’s authority with respect to Indigenous peoples.

The British Columbia conception of native land management was delineated by Joseph Trutch to Governor Anthony Musgrave, 29 January 1870, and conveyed to secretary of state for the colonies Lord Granville during confederation debates and negotiations with Canada.

The Indians have, in fact, been held to be the special wards of the Crown, and in the exercise of this guardianship Government has, in all cases where it has been desirable for the interests of the Indians, set apart such portions of Crown lands as were deemed proportionate to, and amply sufficient for, the requirements of each tribe; and these Indian Reserves are held by Government, in trust, for the exclusive use and benefit of the Indians resident thereon.

But the title of the Indians in the fee of the public lands, or any portion thereof, has never been acknowledged by Government, but, on the contrary, is distinctly denied. In no case has any special arrangement been made with any of the tribes of the Mainland for the extinction of their claims of possession; but these claims have been held to have been fully satisfied by securing to each tribe, as the progress of the settlement of the country seemed to require, the use of sufficient tracts of land for their wants for agricultural and pastoral purposes.

Canadian native policy had, in certain instances, recognized the existence of a form of Aboriginal title. This was not the policy of British Columbia with the exception of the “Fourteen Agreements” – or Fort Victoria Treaties – concluded by James Douglas under the auspices of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The BC policy was established on the principle of continuous use and occupation with native peoples confirmed in their traditional village sites and “cultivated fields.”

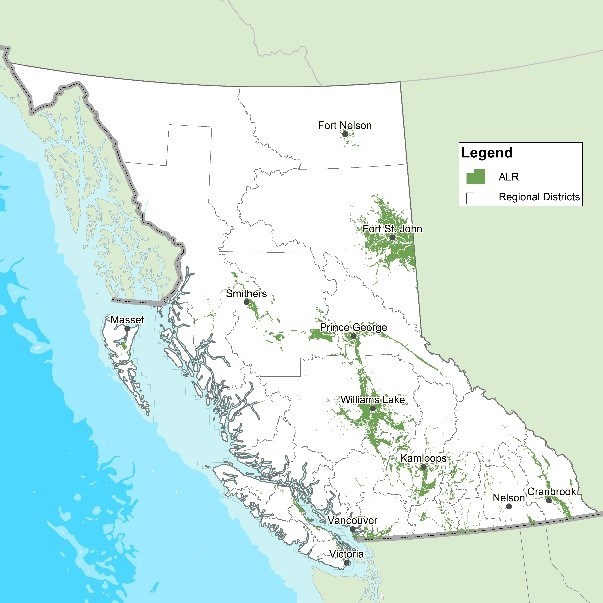

The grant of reserve acreage neither followed a general quota per capita allowance, nor endeavoured to relocate Indigenous peoples to larger reserves outside traditional lands (as practiced in the United States and Canada). Instead, the BC policy recognized the (perceived) needs of native peoples while recognizing the larger practicalities of colonial settlement – constrained by the relatively small amount of arable land; only approximately 3% of BC is arable.

With Canadian native policy the amount of arable land was more considerable, and reserves established east of the Rockies were greater in size. Also, where Canada had concluded treaties, compensation was offered and annual annuities paid. Indigenous title had not been recognized in all cases by the Canadian government, but with Canada’s westward expansion into Rupert’s Land, the federal government began to apply a uniform policy of compensation based on past usage. This appears to have been largely a made-in-Canada policy. Neither imperial nor HBC practices had been uniform, nor the prior policies of Canada.

In the case of the Red River Settlement, Herman Merivale, permanent undersecretary of state for the colonies (responding to a missionary who urged the necessity of treaties), wrote at the time of the Fraser River gold rush that:

This letter alludes to one matter which is new to me. . . I mean claims of the Indian tribes over portions of Lord Selkirk’s land [Red River Settlement] & generally over the territories comprised in the [HBC] Charter – The Americans have always taken care to extinguish such rights however vague – We have never adopted any very uniform system about them. I suppose the H.B.C. have never purchased from such claimants any of their land. And I fear (idle as such claims really are, when applied to vast regions of which only the smallest portion can ever be used for permanent settlement) that the pending discussion are not unlikely to raise a crop of them.

The question of imperial recognition of Aboriginal title was further elaborated upon by Merivale – asserting typical English property notions of the time – with regard to the Red River territory.

In the old days no one ever thought of recognizing ‘territorial rights’ in Indians. Charles the second simply made over to the [Hudson’s] Bay Company the freehold of the soil in their Charter territory. According therefore to English real property notions, the Indians had no ‘territorial rights’ within that territory at all . . . I think it might be pretty safely assumed, that no right of property would be admitted by the Crown as existing in mere nomadic hunting tribes over the wild land adjacent to the Red River Settlement. But that agricultural Indian settlements (if any exist) would be respected and that hunting grounds actually so used by the Indians would either be reserved to them or else compensation made.

In Canadian parliamentary debates, Aboriginal title was noted within a joint address to the governor general (for transmission to Britain) that requested the transfer of Rupert’s Land and the Northwestern Territories to Canada. Dated 11 December 1867, it stated:

That upon the transference of the Territories in question to the Canadian Government, the claims of the Indian Tribes to compensation for lands required for the purposes of settlement, will be considered and settled in conformity with the equitable principles which have uniformly governed the British Crown in its dealings with Aborigines.

George Cartier (Macdonald’s Quebec lieutenant and de facto deputy prime minister) and William McDougall (representing the HBC) were subsequently appointed as delegates to participate in London-based negotiations with the imperial government for the transfer of these HBC lands. In the final agreement negotiated between these three parties, no clear directive was made to the Canadian government that compensation of Indigenous claims was required.

As Merivale noted previously, imperial policy did not dictate the extinguishment of aboriginal title, and in the case of Rupert’s Land and the greater Northwest Territories, the imperial government negotiated and confirmed its future participation in native land management decisions. Of Britain’s authority in this regard, George Cartier – on behalf of Canada – stated:

His Lordship [Lord Granville] subsequently requested us to communicate to him any observations which we might desire to offer upon this reply of the Company, and upon certain counter proposals which it contained. We felt reluctant, as representatives of Canada, to engage in a controversy with the [Hudson’s Bay] Company concerning matters of fact, as well as questions of law and policy, while the negotiations with them was being carried on by the Imperial Government in its own name and of its own authority.

It is important to emphasize the imperial government’s continued participation and authority in Aboriginal policy; no clear directives were issued for extinguishment of Aboriginal title (certainly following the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand). And yet their continued role in these colonial matters more than suggests an active knowledge of Indigenous land matters in British North America before, during, and after BC’s confederation with Canada.

This is an important point that will be further explored in Part 3 of this series – that is, that the imperial government was complicit in the unresolved issue of Aboriginal title that continues to haunt British Columbia today.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Read Part 1 of Daniel Marshall's series on the original issues and negotiations the led to BC joining Confederation.

- Robert Amos looked back at EJ Hughes's work in Vancouver Island.

- One of BC's most enduring legends - Pitt Lake Gold - was the subject of a new book by Fred Braches.