Many years ago in Montreal, during the height of the Quebec separation debate, I announced to some new Quebecois acquaintances that in the past, British Columbia had also threatened to secede from Canada.

“Really!?” was the excited and enthusiastic reply.

“Yes,” I said, “as far as we are concerned, if anyone should leave Canada, it should be Ontario!”

Incredulity was quickly replaced with laughter, and these proud French Canadien nationalists became immediate friends – and kindly ordered the next round of drinks, too!

In 1871, British Columbia’s long-held dream of a transportation link to eastern North America seemed assured when a promised transcontinental railway became enshrined in the Terms of Union Treaty by which B.C. joined Canada.

Indeed, for some, without the Pacific Railway there could be no Confederation.

If it were to compete with the United States, Canada desperately needed access to the Pacific Slope, and so further promised and enshrined in the Treaty that railway construction would begin within two years of the date of Confederation – and be completed in ten.

This key promise was the dealmaker. In short order, it almost became the dealbreaker.

British Columbia’s enthusiasm was not shared by successive federal governments. The obligation for the commencement of construction within two years was carried out only in symbolic form, just one day before the expiry date of July 20, 1873.

In keeping with his order-in-council, which established Esquimalt as the terminus, Sir John A. Macdonald ordered a survey party to run a location line for a portion of the proposed Island Railway. Victoria’s aspirations of becoming the Pacific terminus for a transcontinental nation had argued in favour of a rail line that followed the present-day E & N Railway, but one that would extend to Campbell River, then crossing the Valdez group of Islands to Bute Inlet, and ultimately the Chilcotin Plateau to the Cariboo and beyond.

Though Macdonald seemingly favoured this course, the federal government – having kept its promise, if only minimally – returned to inaction. The absence of railway construction became apparent once more, especially with the election of Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal Government in 1873.

Mackenzie had previously infuriated the Pacific province, saying the Terms of Union were “a bargain made to be broken,” and quickly rescinded Macdonald’s 1873 Order in Council naming Esquimalt the terminus.

The provincial and federal governments argued over the question of relaxing the ten-year timeline – and constructed nothing but deadlock.

This impasse remained until both parties agreed to an impartial mediator: Lord Carnarvon, Colonial Secretary of the Imperial government, who insisted that his decision “whatever it may be, shall be accepted without any question or demur.”

Carnarvon’s decision guaranteed the building of the E & N Railway, and as long as the Bute Inlet Route was still seen as viable (which it was), Victoria’s hopes of being part of the main nationwide railway prevailed.

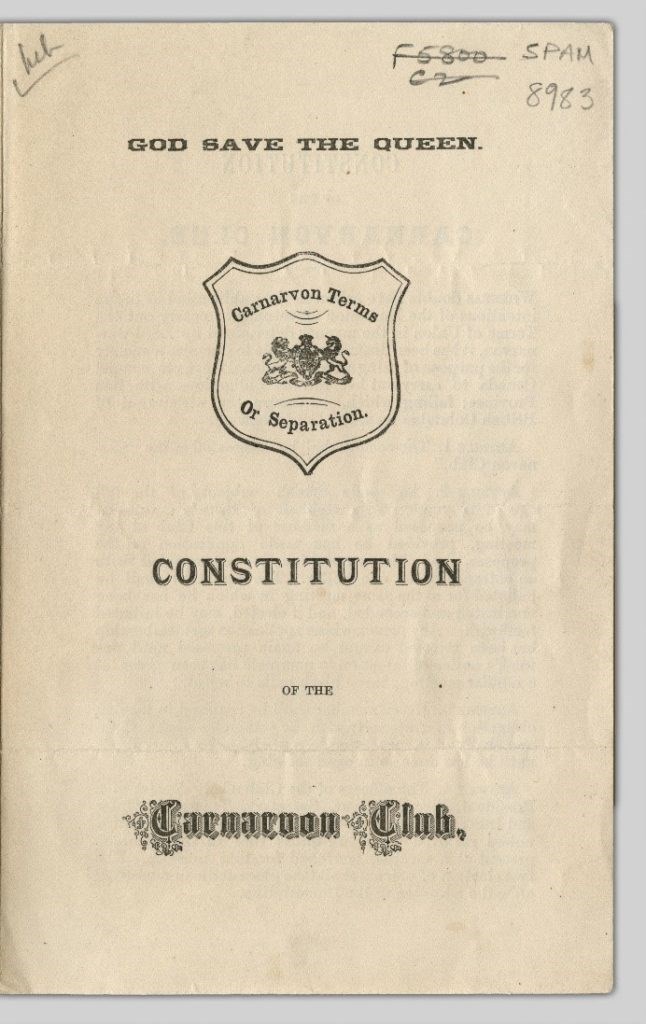

Yet, even after Carnarvon made his decision, procrastination continued under the Mackenzie Government and became a concomitant to the rallying cry of ”Carnarvon Terms or Separation.”

Ottawa’s continued default on the Terms of Union acted as a catalyst for political opposition, waged against not only the federal government, but also the provincial government: they had to ensure the Carnarvon Terms were kept. This naturally led to the establishment of the Carnarvon Club, which before the introduction of the “old” line parties of Canada, played an important and influential role in the politics of the province.

In writing to Sir John A. Macdonald, Joseph Trutch described the political mood such that “The temper of our community is greatly excited and set against Canada and the Canadians by the nonfulfillment of the Railway Clause of the Terms of Union and especially by the tone and manner regarding it taken by those who have expressed a desire for some readjustment of the obligations of Canada.”

Talk of secession was becoming so frequent, it was decided a viceregal visit by Lord Dufferin, Governor General of Canada, might help to mend relations. At a large meeting held at Philharmonic Hall in Victoria, an address was prepared and approved for presentation to the Governor General:

“The action of the Dominion Government in ignoring the Carnarvon settlement, has produced a wide feeling of dissatisfaction towards Confederation…if the Government fails to take practical steps to carry into effect the terms solemnly accepted by them, we must respectfully inform your Excellency that, in the opinion of a large number of people of this Province, the withdrawal of this Province from Confederation will be the inevitable result.”

Upon his arrival in Victoria, this was made immediately known to Lord Dufferin – but nevertheless, he declined the address prepared for him and instead spoke privately with the meeting’s deputation and informed them that the Island Railway would be abandoned.

To quell the secessionist threat, Dufferin further warned that “the Crown would allow the Island to go; but… the Mainland will be held to the Dominion by inducements of self interest which the building of the main line will furnish.”

In other words, if the threat of separation continued, Bute Inlet as a railway route would be overturned and “the proposed line of the Pacific Railway might possibly be deflected south” to New Westminster.

This was the political climate the Governor General’s visit was supposed to alleviate, but Dufferin’s consistent refusal to recognize B.C.’s legitimate constitutional complaints intensified things instead. As a direct result, on September 9 1876, the Carnarvon Club was formally established with the following main objective:

“… to organize a society for the purpose of using all constitutional means to compel Canada to carry out her railway obligations with this Province; failing which, to secure the withdrawal of British Columbia from Confederation.”

Political opposition took the form of a two-pronged attack. The Mainland, and New Westminster in particular, believed that the Island Railway would secure the Bute Inlet route over their preferred Fraser River route.

Premier A.C. Elliot’s provincial government caused considerable consternation among Victorians, and especially Carnarvon Club members, when he became an ally of Mackenzie’s Liberal Government, and therefore, Liberals themselves working in concert against the Carnarvon Settlement.

Most of Vancouver Island worked not only against the federal government, but also the proponents of the Fraser River alternative which was, as the British Colonist described, “destined to keep the sections asunder and preclude the possibility of united action.”

After the Carnarvon Club’s inception, three mass public meetings were held at Philharmonic Hall, for the express purpose of deciding on “Carnarvon Terms or Separation” and acted as the main political impetus for further provincial legislative action on the question of secession.

The first meeting, September 19 1876, recorded not only an attendance of “Seven Hundred Citizens in Council,” but also a “unanimous vote in favour of separation!”

Supporters of Elliot’s government sounded the alarm. Former MLA W.A. Robertson, cautioned, “I deemed it in the interest of the public, and the people particularly of Victoria, to let it be known that there is in our midst a political Star Chamber (wrongly called the Carnarvon Club) which, while professing to be working in the interest of the Province, is, in reality, wholly and solely run in the interests of a political faction — a faction which is nothing more nor less than the rump of the late (Walkem) Government.”

It didn’t work.

On election day, May 23 1878, Walkem returned to power. Victoria elected all four opposition candidates, and even deprived Premier Elliot of his own seat. Overall, 10 out of 12 opposition members were returned for Vancouver Island. The results led the Victoria Standard to predict that “any opposition…to the new (Walkem) Gov’t on any of the great questions of the day will be unimportant and inconsiderable.”

Indeed, one of the greatest questions of the day was: “Carnarvon Terms or Separation.” Walkem was determined to act, immediately passing the famous secession petition to Queen Victoria, threatening to pull British Columbia out of the Canadian Confederation.

As a pressure group, The Carnarvon Club was the most successful the province has ever seen, having brought down a government.

In its role as a political party incognito, however, the Carnarvon Club was perhaps even more effective, being the only group in the history of British Columbia ever to have succeeded in returning a Premier to power after their political defeat – all before the age of political parties.

What was the Canadian government’s response? Even though the United States had taken the San Juan Islands and threatened to establish guns to control the Strait of Juan De Fuca – a serious security risk for future Canadian shipping interests – Canada quickly acted on its threat and confirmed the Fraser River route for the transcontinental railway.

It secured both the loyalty of the BC Mainland and access to the Pacific Ocean; Victoria and the Island were deemed nonessential to the Canadian national dream.

Had events been otherwise, the settlement patterns of this province would be entirely different; with Victoria a metropolis of the size of Vancouver – just imagine that.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.