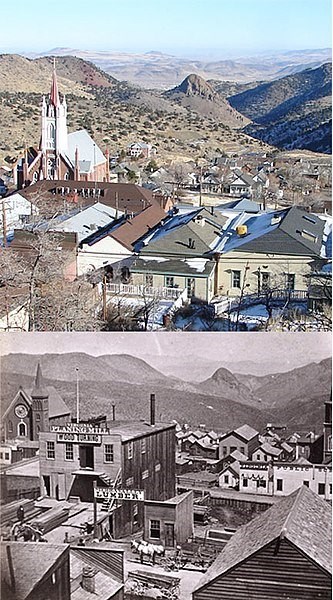

I remember traveling years ago into the sublime landscape of the Comstock Lode country of Nevada, anticipating my soon-to-be quenched thirst – both for a drink, but also for history. This had been the 19th century’s “Silicon Valley” – a place so rich in silver as to have made some of the wealthiest entrepreneurs of their day – the legendary Bonanza Kings of California.

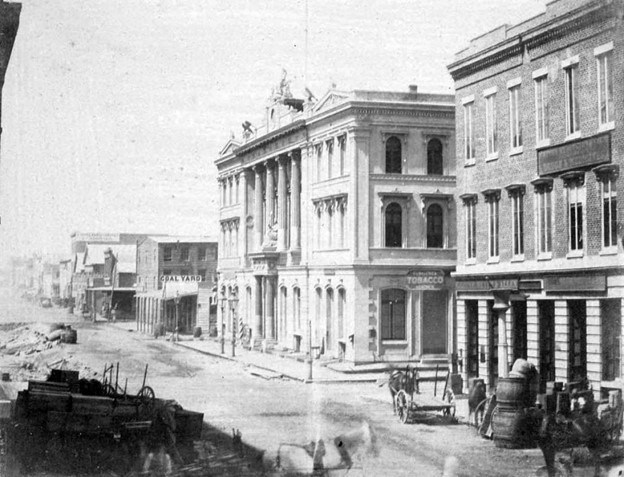

Rolling past the ruins and passing Boot Hill cemetery, we made our way to an old saloon in historic Virginia City – a quite wonderfully preserved gold, or more correctly, silver rush town – a boomtown that sprung up shortly after the Fraser River gold rush of 1858.

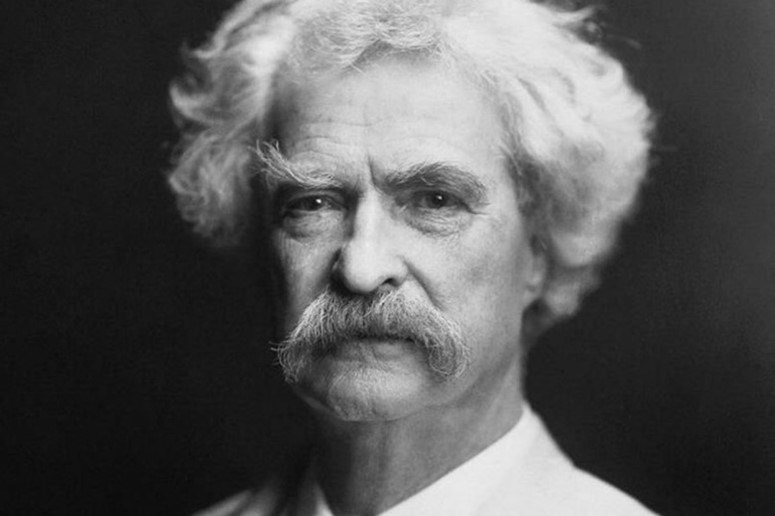

So many who flooded into British Columbia during the Fraser and Cariboo gold rushes made their next stake in Nevada’s White Pine District in the 1860s. Samuel Clemens had lived here for a time; in fact, in Virginia City he adopted his more famous nom de plume, Mark Twain.

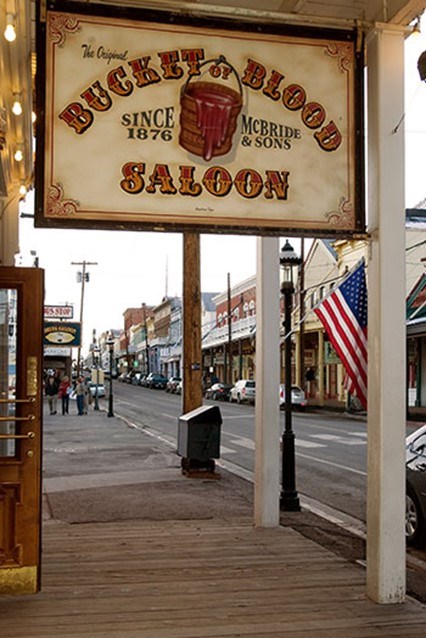

“What saloon should we go to next?” I asked my colleague Alan, both feeling a bit parched, having just come from the Western Historical Association conference in Reno. “That one!” he pointed, and so we crossed to the other side of main street, imagining the thousands of miners who had frequented this once bustling town. We now entered the oldest watering hole of this legendary city – the rather ominously named “Bucket of Blood Saloon.”

Mark Twain once wrote, “To be a saloon-keeper and kill a man was to be illustrious” – indeed, the wild west! Before us was a long wooden bar, old slot machines spinning, frothing pints, and surrounded by a land drenched in hard-rock mining history. What an immense place to contemplate the past, and the amazing transitory, transboundary mining societies that once ranged from California to Australia to British Columbia, and subsequently to such places as Nevada and beyond.

I have always been fascinated by the stories of my ancestors who chased “the golden butterfly” to California in 1849 and then to the Fraser River goldfields in 1858 – part of a natural north-south world that continued well into the early 20th-century; that is, before the reorienting effects of the transcontinental national dream (yes, Sir John A. McDonald’s vision) that shapeshifted BC into the East-West alignment of the new Canadian state.

Meanwhile, my friend had heaped his own small fortune atop the bar – “another round?” he winked. Alan was feeling quite flush, having “broke the bank” at the previous saloon on a gigantic one-armed bandit. I remember the rush of coins spilling out, accompanied to the theme of the TV series Bonanza (which starred Canadian Lorne Greene as the iconic Pa Cartwright.)

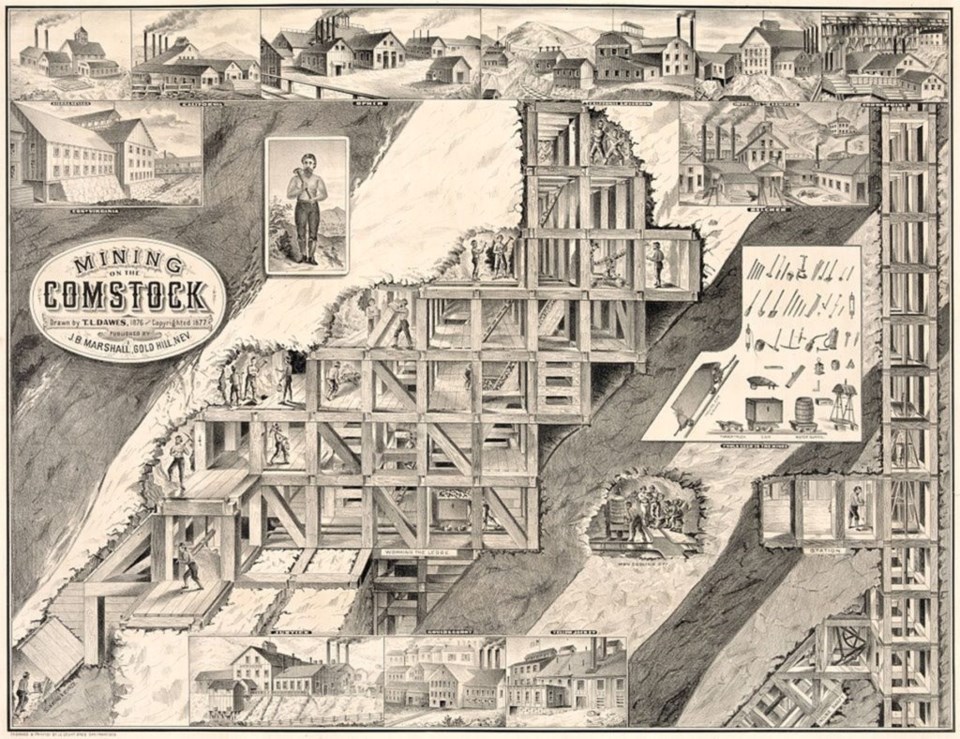

Second pint in hand, soon I was back in the 19th century thinking about these roving miners, and the sort of rags to riches stories that were all too frequent in the chaotic and often lawless days of the California mining frontier.

So many who had joined the Fraser and Cariboo rushes were subsequently found south of the border in mining towns throughout the American West, taking with them substantial amounts of BC gold that, in many instances, financed later and even greater bonanzas – defined as “exceptionally large and rich mineral deposits” or as time went on, “events that create a sudden increase in wealth, good fortune, or profits.”

Here is one such intriguing bonanza story.

Written under the title of A Thing not Generally Known (Victoria’s British Colonist newspaper, 6 February 1878), the story was told of a Cariboo gold miner Jim Wade, “a thrifty, good-natured Irishman, who had made $50,000 or $60,000, by mining and packing at Cariboo, and had visited San Francisco to see the ‘sights’ and invest his money.” For perspective, $60,000 in 1860s dollars is roughly equivalent to $1 million today.

In other words, Jim Wade had struck it rich.

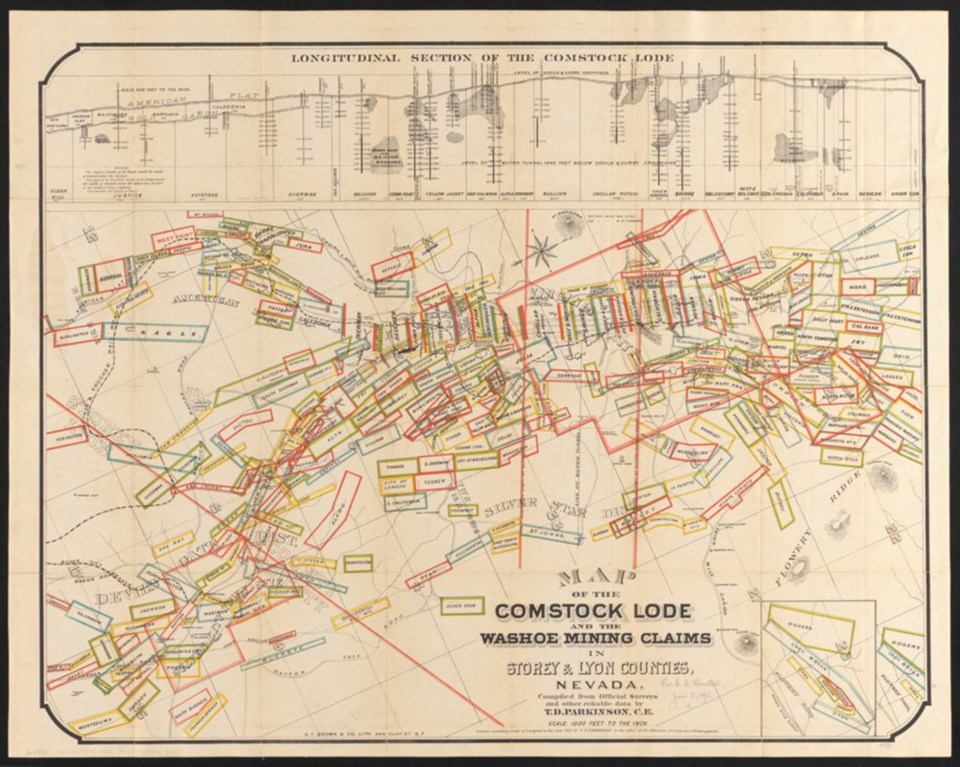

Upon his return to San Francisco, one of the first things he did was to visit his old friends and fellow Irishmen James Flood and William O'Brien, who ran a saloon called the Auction Lunch in the financial district on Washington Street. Apparently Flood and O’Brien had moved their saloon on three different occasions, each time closer to the California stock exchange. Their eatery had become a favourite among stock brokers and mining developers who, while having a few drinks, would offer tips to the barkeeps who began to invest the little money they had in the new Comstock Lode of Nevada.

It takes money, of course, to make money. So, with the arrival of Jim Wade (and his wallet), the two barkeeps hatched a plan: borrow some of their old friend’s newfound wealth, and take advantage of a particularly hot tip. The Colonist reported:

From this man Flood & O’Brien borrowed $35,000 and invested the amount in a low priced stock on which they had obtained ‘points’ from the operators. . . The stock rose steadily from $2 to $3 dollars a share until it touched an almost fabulous figure and then the fortunate Bonanza kings sold out and realized a cool $500,000 apiece. This transaction laid the foundation of the fortunes of these men.

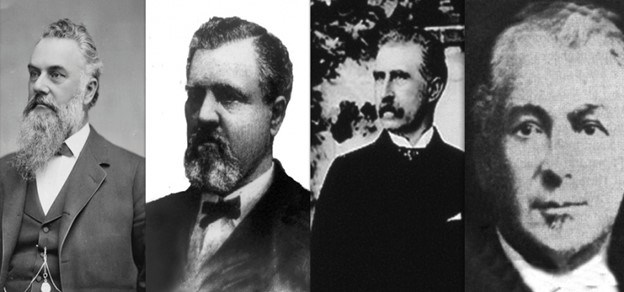

There were in fact four such Bonanza Kings: Flood & O’Brien, the saloon keepers, had formed an association with two experienced Comstock Lode miners: James Graham Fair, a mine superintendent; and John William Mackay, a mining engineer. Consolidating their interests, these four in short order “accumulated $200,000,000, own two banks, the best business real estate in San Francisco, and five of the principal mines on the Comstock lode, and rule the San Francisco stock market.”

It was further reported in the Colonist that “’no dog dare bark on California Street’, without the permission of Flood & O’Brien.” All set in motion by Cariboo gold! The Colonist declared this remarkable turn of events:

A thing generally not known is that on the basis of gold dug from our Cariboo mines has been reared the colossal fortunes of Flood, O’Brien, Mackay and Fair – the Bonanza kings – probably the four richest men, viewed by their present and prospective wealth, in the wide world.

David Higgins, one-time editor and owner of the British Colonist, former owner of the San Francisco Call newspaper (and Speaker of the BC Legislature) expanded further the story of how Cariboo gold created these Bonanza Kings. In his book entitled The Passing of a Race and More Tales of Western Life (1905), Higgins learnt of the tale of Jim Wade’s gold from Thomas B. Lewis, a native of Virginia, “and a heavy loser by the failure of the Harrison-Lillooet route” that had been backed by the BC colonial government as an alternative transportation corridor to the arduous Fraser Canyon route.

Higgins wrote that Tom Lewis after his financial misfortune in BC ultimately returned south of the border and found employment behind a saloon bar:

He had known Flood and O'Brien when they kept the Auction Lunch, a ‘bit’ grogshop near the waterfront at San Francisco [wrote Higgins]. He told me that, while tending bar one day, the partners overheard two brokers, who had dropped in for a beer and a lunch, discussing in a confidential tone a plan for advancing to $100 the price of shares in a certain Washoe mine. A few days before, a packer, named Jem Wade, had arrived from Cariboo with $65,000 in gold. This sum he deposited in Flood & O'Brien's safe. ‘If only we had a few thousand dollars,’ quoth Flood to O'Brien, ‘we could make a fortune.’

‘Let's ask Wade to lend us his gold for a few days,’ suggested O'Brien. The idea was acted upon. Wade was asked, and, being an old friend, he consented, and the stock in the mine was secured with Wade's money. Before the firm sold out, the stock rose to nearly a thousand dollars a share. The shares, having been bought on a margin, the liquor dealers realized nearly a million dollars from the investment of $65,000 of Cariboo gold. The next day the Auction lunchrooms were offered for sale, and in the course of a few weeks Flood bought a seat on the stock exchange and became one of the most important men on the board.

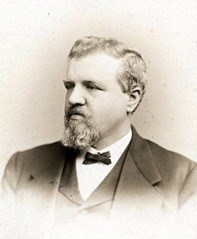

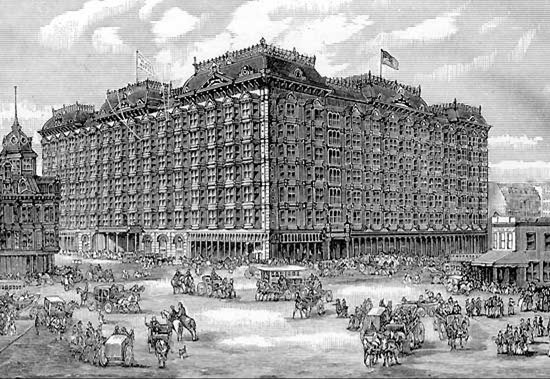

Indeed, all four of these Bonanza Kings made huge, fast wealth. For three years after the discovery of the "big bonanza," their mines produced $3 million per month. Over 22 years of operation, they yielded more than $150 million in silver and gold. Former Saloon Keeper James Clair Flood had particular success, ultimately becoming the President of the Bank of Nevada, based in San Francisco.

In an article entitled “How a Poor Lad became one of the great Money Kings,” Daily Alta California, 22 February 1889, it states that Flood had first traveled to California during the 1849 gold rush and mined on the Yuba River before entering the liquor trade. However, his rags-to-riches story came not from the hard work of sluicing for gold dust – or even serving booze behind a bar – but as a savvy stock manipulator.

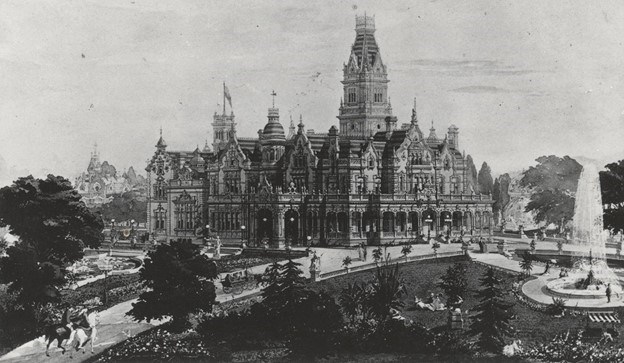

Flood was considered one of the 100 wealthiest Americans of his day, amassing an enormous fortune, and is still known today for having built two great mansions: the James C. Flood Mansion at 1000 California Street in San Francisco; and the incredible Linden Towers in Menlo Park that stood until 1936.

The impact of Jim Wade’s Cariboo gold went well beyond the wealth (and mansions) of James Flood. Along with the former 49er’s increased power and wealth came a fight for financial dominance against rival W. C. Ralston, head of the Bank of California.

David Higgins relates:

One of the pursers on the Nicaraguan line of steamships was W. C. Ralston. He made a lucky turn in stocks, and went on the [stock exchange] board about the same time that Flood made his appearance there. They made heaps of money, and for a long time pulled together. But the day came when Ralston, who meanwhile had become cashier of the Bank of California, was ‘short’ on one of the Comstock stocks. Knowing that Flood had a great many shares in the company, he sent for him, and asked him to lend him a sufficient number to make up the deficiency. Flood, who had long secretly disliked Ralston, and now saw an opportunity of ‘downing’ him, refused to grant his request. Ralston flew into a towering passion, and in his rage exclaimed: ‘Look here, Flood, I'll send you back to sell liquor at a 'bit' a glass.’

‘If you do,’ retorted Flood, ‘I'll sell it over the counter of the Bank of California.’

Apparently, Ralston (portrayed by Ronald Reagan in a 1965 episode of Death Valley Days, called Raid on the San Francisco Mint) covered up for many months that he had massively overdrawn his account at the bank, in excess of some $4 million – again, a truly staggering amount of money at the time. Ultimately, he was given 24 hours to make good on the debt.

Higgins recorded what happened next:

He left the bank and went straight to a place where he was accustomed to take a salt-water plunge daily. He disrobed and put on a pair of trunks, all the time conversing and joking with the attendants and a few friends whom he met on the bathing-float. Then he entered the water and swam about two hundred feet from the shore. No one appeared to take much interest in his movements. Certainly not a soul thought for a moment that the good-natured, jovial man who had left the bathing-house a few moments before with a smile and a joke on his lips, was about to dive into the great sea of eternity that circles the world about, and would be seen no more of men . . . That was the last ever seen alive of the banker and broker who for so long a time had controlled the financial interests of San Francisco. A few minutes later he was observed to be floating with the tide, helpless, his face downward, his body partially submerged.

Ralston was dead, seemingly having committed suicide and abetted by James Flood’s refusal to bail him out. The story is even more remarkable, considering this chain of events first set in play by wealth taken from the Cariboo goldfields.

Mark Twain jested in his famous work Roughing It that “The cheapest and easiest way to become an influential man and be looked up to by the community at large, was to stand behind a bar, wear a cluster-diamond pin, and sell whisky.” Perhaps Twain had James Flood in mind, as “no great movement could succeed without the countenance and direction of the saloon-keepers.” This classic rags-to-riches story of 49er James Flood is indeed the so-called Californian Dream.

And what became of British Columbia miner Jim Wade? Once again, the British Colonist provides the clue.

Apparently as of 1878 he was living on a ranch in southern California “prosperous and happy” – but talked “of revisiting the Cariboo during the coming summer to try and make a new strike and, perhaps, create a few more Bonanza kings.” And this makes me wonder – just how many others must have slipped across the 49th parallel with their own quiet bonanzas in past times? It seems to me that we will never fully know.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's two-part tale of two missions to find gold on Vancouver Island made for excellent holiday reading. Here's Part 1, and Part 2.

- If you're in more of a sit back and relax vibe, enjoy Daniel giving a master class on BC history here.

- Last February, Mike Robinson shared a three-part story of his experience working on getting approval for the Mackenzie Valley pipeline proposal. Not only are the lessons never more relevant - it's just a really good tale.