These last weeks have kept me riveted to the news.

The fury of massive flooding, destruction of homes and livelihoods, roads and bridges gone, supply chains down – and many sleepless nights following firsthand accounts from friends of the devastating effects of the atmospheric rivers that pummeled our province.

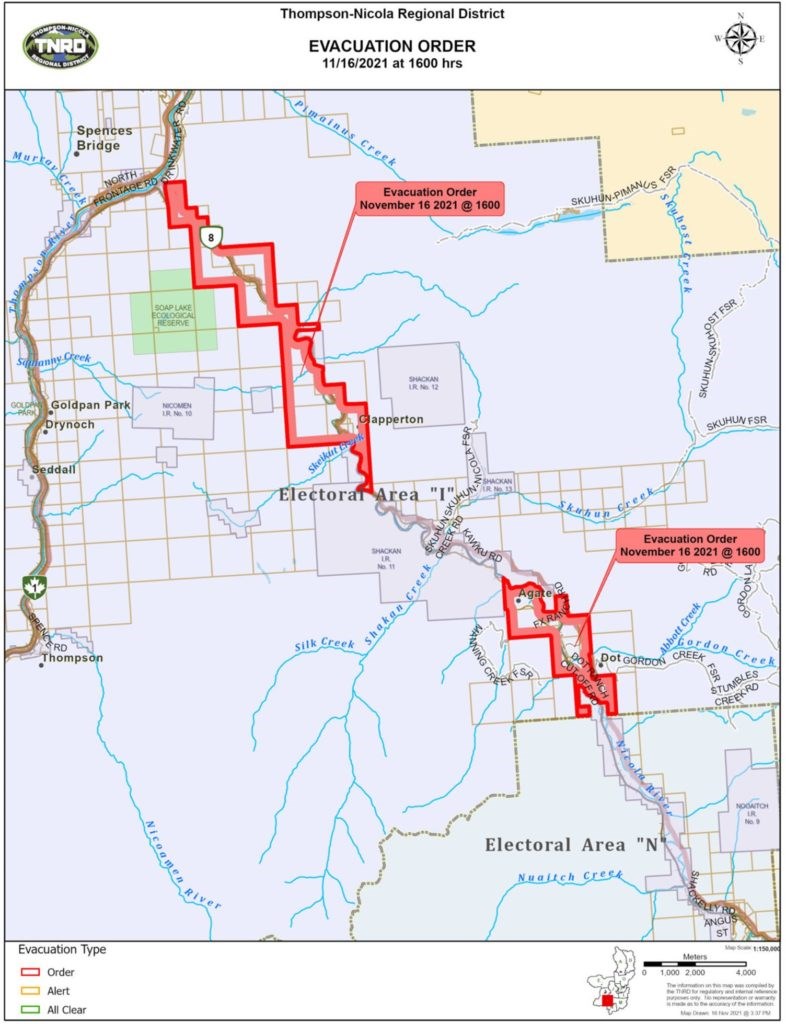

Abbotsford, Chilliwack, Mission and Hope – and plenty of individual folks I know throughout the Fraser Valley – have been hit so hard. The scale of the destruction of livestock is immense. And what of the BC Interior? Princeton, Tulameen, Merritt – indeed all along the Nicola River to Spences Bridge – savaged by raging torrents. Huge swaths of ranch and Indigenous reserve lands, such as those of the Shackan people, swept away, with voluminous silt spilling into the Thompson River.

Once again, as with last summer’s wildfire season, immediate news of these tragedies was slow to make the mainstream press – Spences Bridge and Highway 8 (now utterly destroyed) in particular. These communities, while feeling distant, alone, and neglected, are not by themselves in the sheer expanse of this disaster.

Mike Farnworth, Minister for Public Safety (and also solicitor general and deputy premier), recently confirmed “we’re dealing with an unprecedented time right now in our province’s history,” and that we have just experienced “probably the largest natural disaster in the history of the country.”

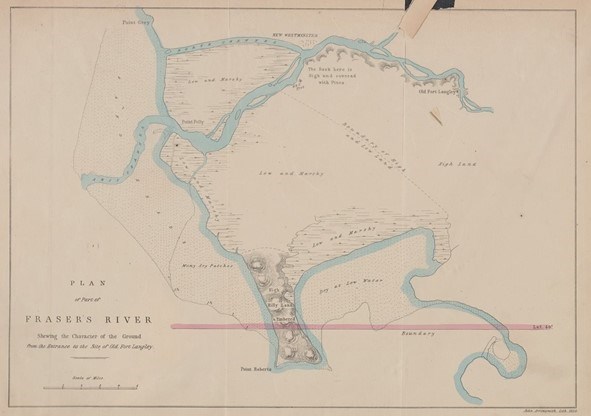

I proceeded on horseback from Langley with the intention of riding the whole way to Hope; that intention could not however be fully carried into effect as Frasers River had overflowed its banks, and inundated the low plains through which the road has been injudiciously led. After a ride of 13 miles our progress was arrested by a flooded plain, impassable in its present state for horses, and we were therefore compelled to seek the river and to proceed by canoe.

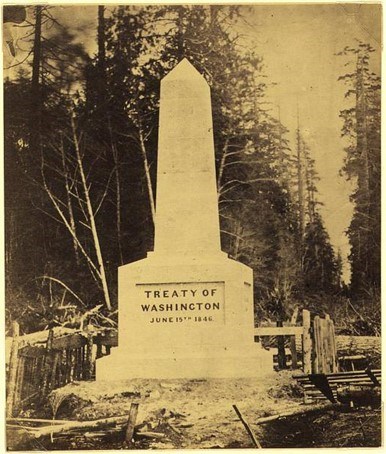

It would seem there have been more than a few injudiciously located roads ever since. Douglas was certainly not the first colonial emissary to the Sumas Prairie region. In fact, he was preceded in 1858 by a company of Royal Engineers charged with locating the international boundary along the 49th parallel.

While American counterparts had established a base camp at Semiahmoo under Chief Commissioner Archibald Campbell (establishing an initial boundary location on Point Roberts), British forces led by Captain John S. Hawkins established a camp near Sumas Prairie, with a second at Cultus Lake.

But then the winter rains set in, and the legendary Sumas Lake mosquito infestations – well known to both Indigenous peoples and gold seekers alike – made their work a “perfect agony.”

One of the men recorded:

“We sit wrapped up in leather with gloves on and bags round our heads & even that cannot keep them off; none of us have had any sleep for the last two nights & we can scarcely eat.”

“My hands, during the last few days, have been so swollen & stiff that I could hardly bend my joints & have had to wrap them in wet towels to be ready for the next day's work; one's hands are literally covered with them when writing & even when wearing kid gloves the bites through the needle holes in the seams were sufficient to produce this. Each mule, as it is packed, is obliged to be led into a circle of fires continually kept up, as they are quite intractable when worried by mosquitoes; two of [them] have been blinded & 6 of our horses were so reduced that we had to turn them out on the prairie and let them take their chance of living. I never saw anything like the state of their skins, one mass of sores. Our tents used frequently to be so covered with mosquitoes inside & out, that it was difficult to see the canvas . . . . We are all of us, as you may imagine, a good deal pulled down by want of sleep & continual irritation.”

Nevertheless, these intrepid Royal Engineers laboured through the entire season, marking the line from Chilliwack to the crest of the Cascade Mountains. As the Chilliwack region had become a base in 1858 for the Royal Engineers, perhaps it is no surprise that some 88 years later in 1946 the federal government established Camp Chilliwack as the permanent home station for the Corps of Royal Canadian Engineers. A further 20 years after that, Canadian Forces Base Chilliwack was born, in 1966.

In my previous article I noted how the Canadian Army took charge of all dikes in the lower Fraser Valley during the flood of 1948. Clearly, they were a major force at that time, and with troops based at Chilliwack, the response was immediate.

But in 2021, there remains no military base, as CFB Chilliwack was closed in 1997. At the time, there were about 1,600 personnel at Chilliwack (1,000 military and 600 civilians were employed, not including some 700 students enrolled in the Canadian Forces School of Military Engineering and the Canadian Forces Officer Candidate School).

Imagine if CFB Chilliwack still existed during this latest catastrophe – again, “probably the largest natural disaster in the history of the country” – and so close to the failing dikes! Instead, all we got were some 500 troops shipped out from across the Rockies. When I talk with British Columbians throughout southwestern BC (including a retired CAF brigadier general), the response has been always the same – “It’s a drop in the bucket!”

Why was our need for troops on the ground so severely underestimated? I decided to investigate further, beyond the general consensus of the ball simply having been dropped.

Operation LENTUS is the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) response to natural disasters in Canada. In times of natural disaster, provinces may ask the military for help.

Operation LENTUS then follows an established plan of action to support communities in crisis, and their objectives include “to respond quickly and effectively to the crisis” and “to stabilize the natural disaster situation.” Furthermore, “the number of people deployed is based on the scale of the natural disaster,” but most interestingly, it is up to provincial authorities to submit a request for emergency assistance, which outlines just how much help is required.

The CAF then establishes how many troops to send into the disaster zone. From the Canadian National Defence website, apparently “In recent years, this has been anywhere from 60 to 2,600 members. The operation could also include ships, vehicles, aircraft, and a variety of equipment.”

During British Columbia’s immense wildfires of last Summer, Operation LENTUS deployed a total of 300 CAF personnel from 5 July to September 5. Was that sufficient? We now know that the destruction caused by wildfires was a significant factor in many of the mudslides this Fall that obliterated our transportation routes. But for comparison, the severe floods of Quebec in 2017 forced that province to seek help – and help arrived, with a whopping 2,600 CAF members (and reservists) immediately deployed, along with 400 trucks and armoured vehicles, 7 helicopters, and a Halifax-class frigate, among other assets.

Clearly, the 500 army personnel deployed to BC is, indeed, a drop in the bucket.

This is not to condemn the Canadian Armed Forces; the request for military assistance had to come from the provincial government. Presumably that request would have come from BC’s Minister of Public Safety in tandem with the Premier’s Office (as confirmed to me by a former BC cabinet minister).

I suspect that the BC government severely underestimated our need for military assistance. I wonder if we will ever know the full extent of the BC government’s request for emergency support?

In the meantime, and as but one example, in remote communities like Spences Bridge on Highway 1, and all along Highway 8 that follows the Nicola River, folks I talk to have been completely cut off by the scale of this disaster and seemingly forgotten.

“It feels like we are living on a cul-de-sac,” lamented one Spences Bridge business owner, with both Highways 8 and 1 closed. And even if they could travel south for supplies and assistance, their nearest neighbour, the town of Lytton, no longer exists.

Highway 8 is destroyed, now and for the foreseeable future, and the only access to their farms, ranches and Indigenous reserve lands, is by helicopter. Where is the military? I heard from a reliable source that they finally got a couple of helicopter rides, but it is difficult to communicate with a community that still has no cellphone service. Must these folks depend on the remaining crumbs of provincial support?

The BC Emergency Program Act states quite explicitly what the powers of the provincial minister concerned are during a state of emergency. Among them, to “cause the evacuation of persons and the removal of livestock, animals and personal property from any area of British Columbia that is or may be affected by an emergency or a disaster and make arrangements for the adequate care and protection of those persons, livestock, animals and personal property.”

Clearly, this did not happen in a timely manner. This begs the question – why did we close CFB Chilliwack?

British Columbia is the third-largest and fastest-growing province, and today we have no remaining regular army force. The government of Premier Mike Harcourt should have strenuously objected to the closure of CFB Chilliwack. And in the case of Operation LENTUS, it is up to the provincial government to make the demand. So what was that demand? Someone should be asking.

Whether the wildfires of last Summer, or now the floods of this Fall, on both occasions the BC government simply did not act quickly enough. It is all fine and well to declare yet another state of emergency, but we needed significant numbers of boots on the ground from the start.

Apparently, all we had to do was ask.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).