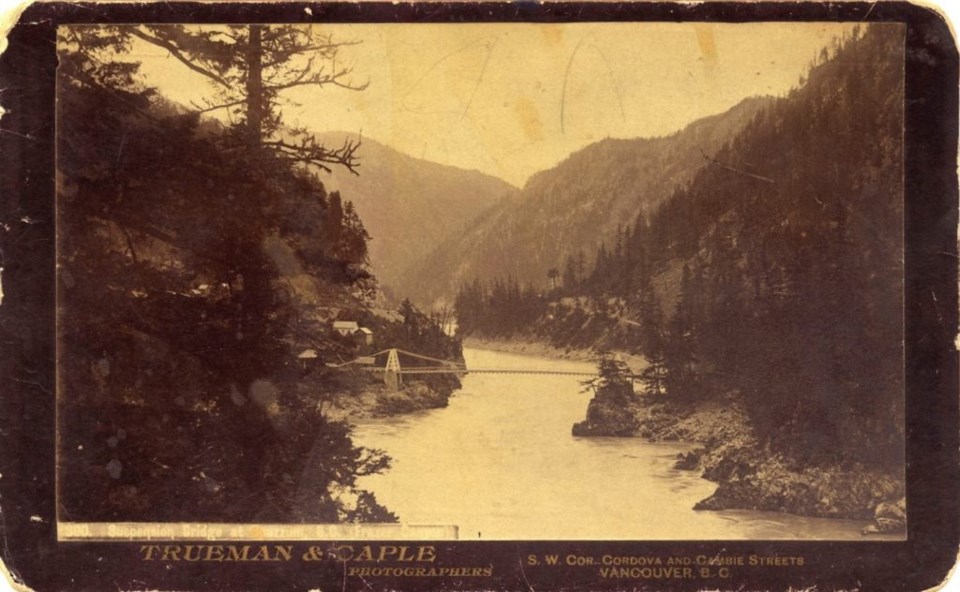

In my travels through the lower Fraser River goldfields over the years I have frequently hiked down to one of the great remaining markers of British Columbia’s past – the historic Alexandra Bridge.

On one occasion I stood at the center of this amazing span with then-BC Premier Gordon Campbell – having been asked to explain the history of the Fraser Canyon War of 1858. This was prior to his attendance at a naming ceremony for the new Chief David Spintlum [Sexpínlhemx] Bridge that crosses the Thompson River in Lytton, recognizing the chief’s role as peacemaker during the tumultuous conflict.

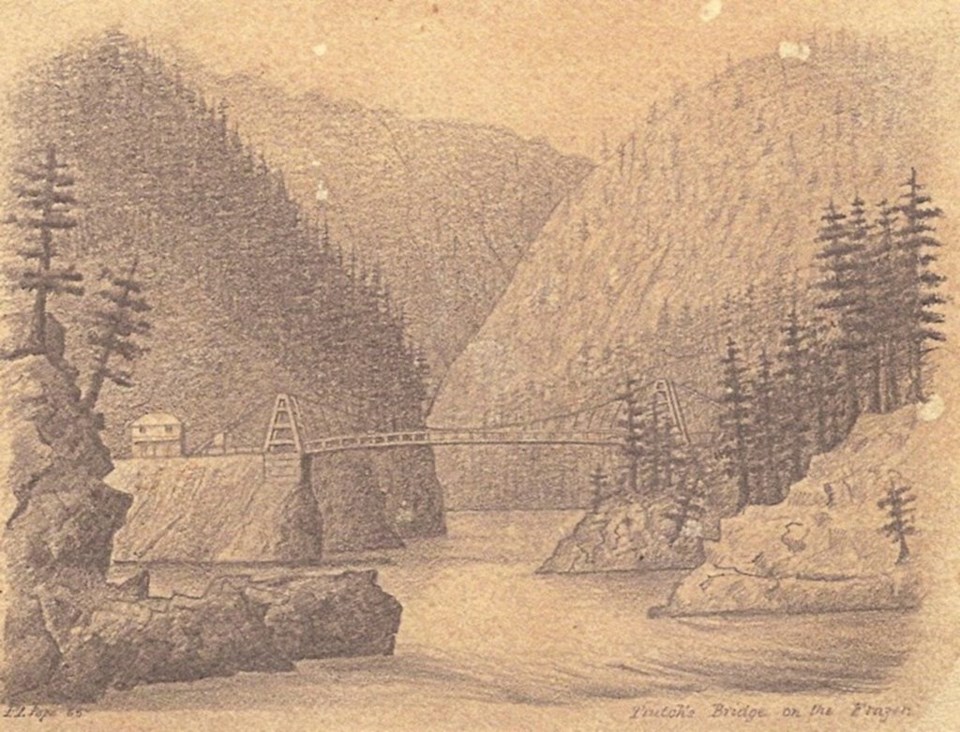

But this forgotten story is about a different conflict that government officials grappled with – the Alexandra Bridge itself that was owned by Joseph Trutch, an engineer, surveyor, politician, and later British Columbia’s first Lieutenant-Governor. Today, his name lives in infamy, particularly for having reversed many of Governor James Douglas’ land policies with regard to Indigenous peoples.

In 1863 Trutch had contracted the San Francisco-based Engineer Andrew S. Hallidie to both design and erect a wire suspension bridge, the latest technology then available in preference to previous constructions built from wood.

Hallidie’s pivotal role is rarely acknowledged. He was subsequently the father of San Francisco’s famous cable trolley system and had already completed at least eight substantial cable suspension bridges in California, “bridges that were able to withstand the ferocious floods that decimated the region during the early 1860s.” Hidden in the California Historical Society’s archives are Hallidie’s recollections of this arduous bridge project and the great difficulties of transporting the heavy, California-made iron and steel components to Yale – the height of steamboat navigation on the Fraser River. Not well known to British Columbians (he has both a building and a plaza named for him in San Francisco), the Californian engineer recalled:

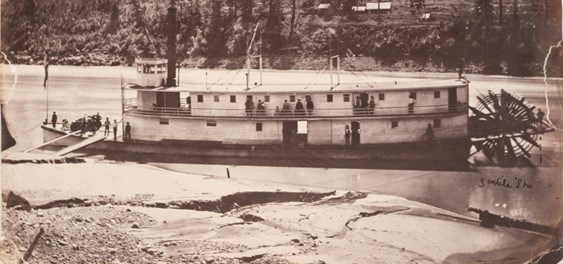

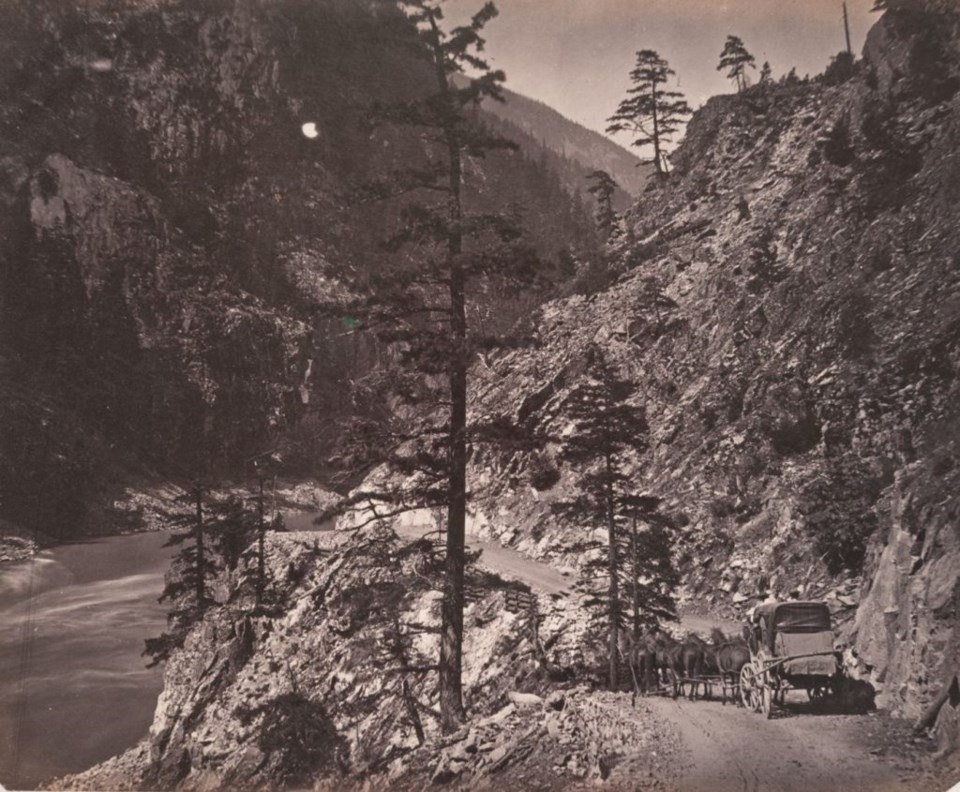

Everything of iron or steel for the bridge was prepared in San Francisco and shipped by steamer to Victoria, Vancouver Island – which at that time was a free port–thence by [another] steamer to New Westminster on the Fraser River and thence by light-draft steamers to Fort Yale. These latter steamers were owned by Captain [Thomas] Wright, who was generally called Bully Wright.

The material for the bridge formed a pretty good load for the stern-wheel steamer [Hallidie continued], but everything went well until on the third day we reached Emery's Bar, about three miles below Yale – here the stream proved too much for her. Spring lines were run out, and every device known to steamboat men tried without success – even a barrel of pitch was broached and fed into the furnace to keep up steam and a sixty-three- pound bundle of wire was hung on the safety valve. The heat of the fires blistered the paint and drove the passengers clear aft, but all without effect, and the captain, one of Bully Wright's sons, decided to land his cargo on the Bar, and returned to New Westminster, where his father gave him a blessing and sent him back with instructions to land the freight at Yale [even] if he made a dozen trips.

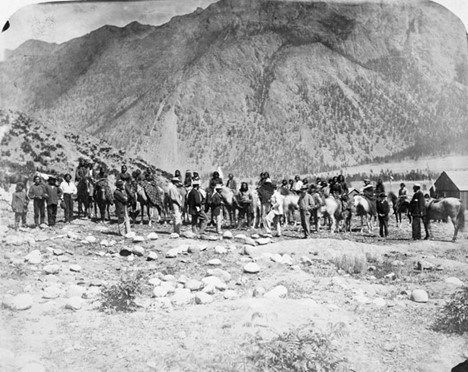

Wright’s son did as his father told him, reducing the cargo weight to one-fourth the size, and made several more attempts to reach Yale with still no success. Finally, the steamship captain enlisted the services of local Indigenous peoples to get the job done, highlighting the crucial role that First Nations played in the building of BC’s gold rush trail.

Hallidie recorded:

He then arranged with Indians to canoe the material up the river to Yale. . . In course of time the material was all landed at the site of the bridge, which was a long distance from anywhere or any place where anything could be obtained, hence great care had to be exercised in providing everything that was likely to be required for the work. The work of bridge building required long exposure to the elements and lengthy absences from San Francisco.

Apparently, this was his last bridge-building experience. Evidently the difficulties encountered with the Fraser River project hastened his decision “to devote himself exclusively to the development and manufacture of wire rope” – certainly a much sought-after commodity during the silver mining rush of the famous Comstock Lode in Nevada.

Shortly after the completion of the new toll bridge in 1863, Joseph Trutch became both the BC Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and the Surveyor-General of the Colony of British Columbia. Trutch was appointed to the position of Chief Commissioner by Governor James Douglas in 1864, while his position as Surveyor-General was confirmed by the secretary of state for the colonies, the Duke of Newcastle. Indeed, there were many high testimonials with regard to Trutch’s professional capabilities.

Douglas’ decision to recommend the appointment of Trutch just prior to Governor Seymour’s arrival suggests to me that the soon-to-be former governor wanted to ensure a continuity of land policies that he had inaugurated, and someone capable of transitioning the once-provisional colony into a formally-surveyed legal status.

Prior to his arrival in BC, Trutch had been the assistant surveyor in the Oregon Surveyor General’s Office. While “Trutch’s Bridge” is remembered today as an amazing technological feat, his better-known legacy was the downsizing of Indian Reserves throughout the province of British Columbia, a policy that seemingly overturned the previous work of Governor Douglas.

Governor Seymour confirmed the Trutch appointments, but also was compelled to question them as contravening well-established Colonial Office rules. In the “Rules and Regulations for Her Majesty’s Colonial Service,” it stipulated that “No Public Officer is to undertake any private agency in any matter connected with the exercise of his public duties.” While certain Imperial authorities were of the opinion that the appointments should stand, others continued to maintain that Trutch must divest himself of his bridge-holdings.

Trutch had, in fact, alerted his colleagues to the potential conflict during the first session of the BC Executive Council:

I feel it necessary at once to request you to bring to the notice of His Excellency the Governor that I hold Private interests in the Public Works of the Colony, which might perhaps be deemed to conflict with the Public duties of an officer in charge of the Lands and Works Department. . .

Should His Excellency consider that my retaining these Charter rights would detract from my official usefulness I am prepared to negotiate for the transfer to the Government of my interests, for an equivalent in money – the amount to be determined by appraisement or by a decision of a referee in the usual manner of business.

I would add however that, having reflected maturely on this subject, I have come to the conclusion, that my continuing in position of these Toll-rights is not incompatible with the faithful discharge of my official functions, and that I should not hesitate therefore to enter upon the duties of my office whilst still retaining my existing interests.

I desire however to submit this matter, most respectfully, for the decision of His Excellency the Governor.

The Executive Council was of the unanimous opinion that Trutch could not hold public office while retaining his private interests, particularly in the Alexandra Toll Bridge.

Governor Seymour agreed to Trutch’s proposal to contract an independent appraiser to assess the value of projected tolls during the remainder of the government charter, in order to calculate compensation. The manager of the Bank of British Columbia was selected, and calculated, at a conservative estimate, that the revenue of the bridge would be £58,000 over the seven-year period, and recommended that Trutch accept £40,000 from the government. The Executive Council unanimously rejected this proposal.

The Trutch offer to sell his bridge must be placed in historical context.

First, his dual appointments would pay him an annual salary of £800. Clearly, without appropriate compensation for his toll-bridge interests, Trutch would consider this a huge personal loss. Second, the colony of British Columbia was in no position to purchase the bridge; they had little in the way of revenue, and nothing but increasing debt (the most compelling reason for BC to ultimately join Canada) due to ambitious road-building projects undertaken to serve and supply the ever-shifting gold rush centers of early BC.

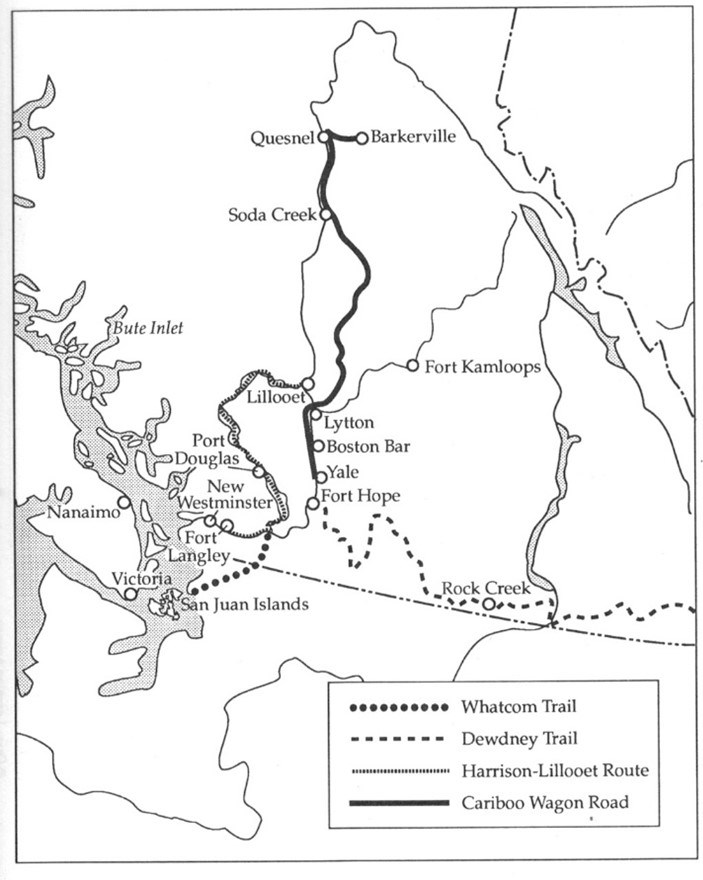

Conflicts such as these were common throughout the early history of British Columbia; it was always difficult to attract qualified civil servants at considerably lower wages than what could be potentially made in the gold rush. Further compounding this problem was the nature of competing routes of communication in the colony, whereby private interests might be attached to one road over another. Trutch’s interest in the Fraser River corridor was, in effect, in direct competition with the Harrison-Lillooet route that had been completed earlier in order to completely bypass the treacherous Fraser Canyon.

With the toll-bridge’s value high and government coffers seemingly low, the issue was, in effect, deadlocked for many years. Trutch’s solution was essentially to transfer all his private toll-bridge interests to his brother John – yet Seymour still had reservations about this new arrangement. His deputy, Arthur N. Birch, on behalf of the colonial government, responded that “I do not consider that Mr. Trutch’s arrangements with his brother in any way alters his interest in the Alexandra Bridge.” Nevertheless, “I do not consider that there is a[nother] gentleman in this Colony capable of filling the appointment.”

Meanwhile, the Cariboo rush to the north (in addition to the Big Bend gold discovery on the Columbia River) increasingly captured the imagination of the economically depressed colony, and quick action demanded immediate road building expertise. Trutch was dispatched without delay.

Seymour solved his dilemma, for the moment, by the expedient solution of limiting the powers given to Trutch, effectively denying him jurisdiction – and indeed influence – in the area from Harrison River in the south to the hub town of Clinton in the north.

This mutually-agreed upon prohibition was in effect during Seymour’s absence from 1865 to 1866. Seymour further elaborated to the Duke of Newcastle:

There are two great routes from New Westminster to the gold mines of the Cariboo. They run together up the Fraser to the mouth of Harrison’s River. The ‘Douglas Lillooet’ line here diverges and follows the last named river into Harrison’s Lake. By ‘portages,’ Lillooet, Anderson’s and Seton’s Lakes are successfully reached; then the line rejoins the Fraser which it crosses and runs over land to Clinton where it forms a junction with the conflicting ‘Yale-Lytton’ route. From this point there is but one established road to Cariboo. The alternative mode of proceeding from the mouth of Harrison’s River to Clinton, is by navigating the Fraser as far as Yale, and then travelling by the great trunk road which crosses the main river at Spuzzum, and Thompson’s River a little above Lytton. Both of the rival routes are kept up by tolls. Vested and conflicting interests having sprung up in each line. . . if the traffic on the first named line be impaired, the profits on the Second increase. . .

Mr. Trutch has been appointed Surveyor General. He retains his property, in the bridges for the present. I will therefore only employ him in works above the Clinton Junction or below the mouth of Harrison’s River. He will, with such assistance as I can afford, at once lay out the line of road into Cariboo.

With these renewed confirmations of the Trutch appointments, though circumscribed, Birch instructed Trutch accordingly:

The Public will expect from the Government, independent of the Surveyor General a special supervision over the claims of those living on the Douglas-Lillooet or Hope-Kootenay [“Dewdney Trail”] lines of road. The Governor will inform the Secretary of State that he has made the best arrangement he could under the circumstances and that he has no wish that they should be interfered with. But he trusts that you will not relax in your efforts to find a purchaser for the Alexandra Bridge.

No purchaser for the bridge was forthcoming during these years, perhaps due in part to the “boom and bust” nature of BC’s early gold rush economy. But in 1894, not even Andrew Hallidie’s bridge engineering – originally designed to withstand the flooding of California rivers in the 1860s – could survive that year’s massive rise of the Fraser River.

The bridge (a 268-foot span, a 90-foot clearance from the river, and a 3-ton load capacity) was destroyed, and portions of the Cariboo Road swept away. The remaining structure of the bridge was subsequently dismantled, the railway now superseding the Old Cariboo Waggon Road. Not until the dawn of the automobile era was the Alexandra Bridge reopened in 1926 . It was built upon the original 1863 pilings, while the new bridge was elevated a further 10 feet.

This second Alexandra Suspension Bridge was used by automobile traffic until 1964, when a third bridge of the same name was built farther downstream on the Gold Rush Route of Highway No. 1.

Today, there is a growing community-based, movement to save the historic 1926 bridge by both the Spuzzum First Nation (the bridge stands in the traditional territory of the Nlaka’pamux people) and the New Pathways to Gold Society.

Since 2009 the New Pathways organization has partnered with the Spuzzum Nation “to save the historic 1926 Alexandra Bridge and develop the adjacent 55-hectare Alexandra Bridge Provincial Park site’s heritage tourism potential” – recognizing that the iconic bridge is situated on an ancient Indigenous crossing-point that “has been a transportation hub for 10,000 years, making it B.C.’s original Gateway Project.”

This is indeed true. Hopefully Alexandra Bridge will not suffer the same fate as the recently demolished Spences Bridge farther north.

Concurrent with the public’s growing demand to save the Alexandra Bridge is a similar concern to save the old Alexandra Lodge, a road house property that includes the historic Chapman’s Bar gold mining site of 1858, and quite possibly the location of the lost Indigenous village of Tikwalus that was set ablaze by miner-militias during the Fraser River War.

There is a small cemetery by the old lodge (just next to Hwy No. 1) that contains many members of the native Chapman family, grave markers that are mute testimony to the family’s earlier presence there, and to my mind, the likely descendants of the Tikwalus village.

If memory serves, I recall once examining the native testimony taken by the McKenna-McBride Commission (1913-16) with regard to the Alexandra Lodge property and that there were, at one time, three conflicting claims of ownership to this historic property.

During the Fraser gold rush an earlier version of this road house once stood, and with it possibly a crown grant or preemption right to the land was issued. But by the time of the railway, this earlier claim had been largely lost to memory, the Cariboo Road defunct, and a second claim – the transfer of the railway corridor from BC to Canada – technically had included this property. The McKenna-McBride Commission, charged with investigating the previous Indian Reserve cutbacks initiated by Joseph Trutch, subsequently discovered a third claim to this property that predated the others, and that was the claim made by the native Chapman family. The commission collected evidence that suggested their occupation to the time of the gold rush (and undoubtedly far beyond that).

The commission was perplexed on how to exactly deal with these three competing claims, and ultimately, they chose to assign a new Chapman’s Bar Indian Reserve farther up the river, while confirming the right of the original road house ownership. The Alexandra Bridge and lodge of the same name are, to my mind, like bookends in the early history of the Fraser River gold rush.

As the British Columbia government continues to grapple with the unfortunate legacies of the past, a concerted effort has been made to purchase additional lands to augment the limited reserve lands left to Indigenous peoples – most recently the government-assisted purchase by the Cowichan Tribes of the Genoa Bay Farm, or the Tsartlip Nation’s acquisition of Woodwyn Farm in Saanich, both in southern Vancouver Island. It’s a small redress, in part, for Trutch’s redefinition of Governor Douglas’ policies.

It seems to me that an excellent next step would be not only to save the Alexandra Bridge, but also the Old Lodge and accompanying Chapman’s Bar property for the Spuzzum Nation, perhaps to even fold it into an expanded Alexandra Bridge Provincial Park under an agreed upon co-management. There are definite possibilities here.

What better way to help bridge some of the inequities of the past?

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's last story was a ripping good yarn - the confounding tale of a "phantom city."

- Daniel mentions the Canyon War, one of the single most pivotal - if largely forgotten - episodes of BC history.

- A lot of bull: Ken Mather looks at the Fraser River Cattle Market from 1858 to 1860. Not that kind of bull, mind you.