A crackdown on COVID-19 cases in the central Okanagan is the first step in B.C.’s new strategy to handle pandemic outbreaks: Keep it regional.

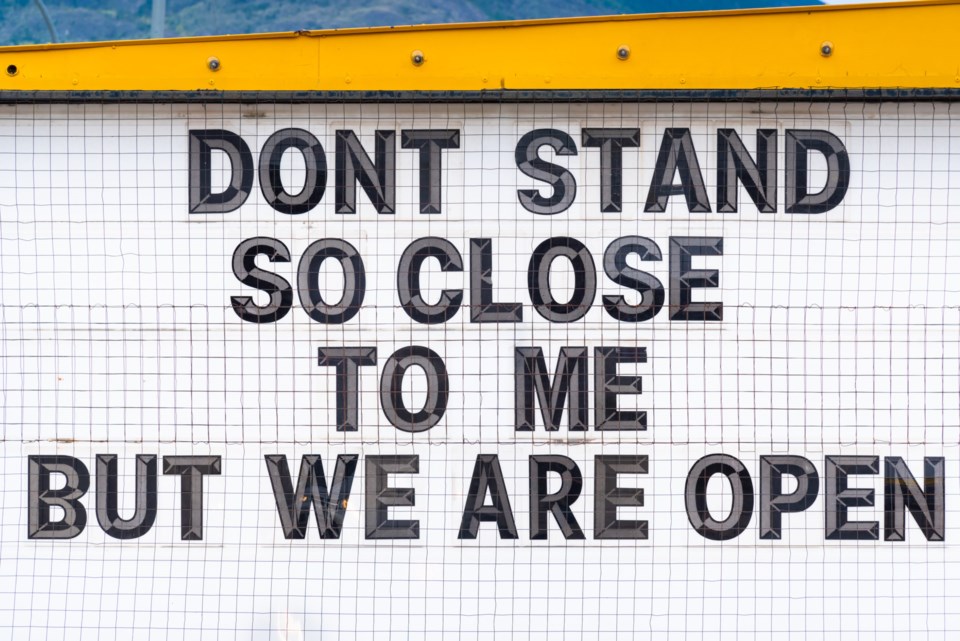

Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry ordered mandatory masks indoors for anyone older than 12, restrictions on public gatherings and a recommendation against travel to the region as the areas of Kelowna, Peachland, and Lake Country to deal with an outbreak that is now responsible for more than half the daily cases in the province.

The targeted restrictions make a lot of sense as a first step to try and contain higher-than-average case counts in a particular part of the province.

Which makes you wonder why B.C. wasn’t doing this sooner?

Henry has repeatedly ruled out regional restrictions since the start of the pandemic in March 2020, saying the province needed to treat COVID-19 like it was in every community and not allow anyone to let their guard down.

It was such a core part of her philosophy that it led the province to refuse to publish detailed information on case counts by community, for fear that it would both stigmatize the people in hard-hit areas but also allow those in communities with fewer cases to become complacent and stop following public health restrictions.

Public pressure and a leaked document showing B.C. health officials were tracking community data forced Henry into a rare backtrack earlier this year, after she begrudgingly agreed to share the neighbourhood case counts.

But all that, apparently, is well in the past.

Because going forward, Henry has made it clear B.C. intends to name communities with outbreaks, reveal their case counts and also target them with specific restrictions to try and prevent the spread to other regions.

The key difference, she said, is the widespread availability of vaccines, which allows health officials to flood a community with life-saving medicine. As part of the central Okanagan crackdown, B.C. shortened the span between first and second dose in the region only, allowing residents to get earlier access to a second shot than elsewhere in the province, in a bid to vaccinate more people.

“We don't need to take as broad across-sector or across-province restrictions because we have vaccine now,” she said.

“So yes, this is a new strategy, and it is a new strategy because we have high immunization rates. So that means the virus is not going to spread as widely and as rapidly as we saw it even a few months ago… so we're now in a new place and in this new place, part of our restart thinking, it is being able to manage it locally because we have such high levels of immunization in most places around the province.”

It’s hard to argue with the approach - even if it is different than the way B.C. previously managed the pandemic. It just seems like common sense to focus on communities struggling with outbreaks using community-specific public health orders.

It’s also hard to argue with B.C.’s initial strategy of trying to manage the pandemic as a single province, keeping as many businesses open, as many people working and as many children in school even as flare-ups happened in areas like Surrey and the Lower Mainland.

That initial strategy was clearly evident in how well B.C.’s economy has rebounded from the virus, according to this week’s public accounts. B.C.’s economic growth is higher than most provinces, its unemployment rate has more than rebounded, and it’s posting better-than-expected financial results far earlier than economists had thought.

Key to all that was Henry’s insistence that as much of B.C. stay open for as long as possible - including areas that other provinces shut down for much longer, like construction, gyms, salons, and personal services.

Now, with freezers full of vaccine, and more than enough doses for everyone, B.C. can shift again to a more targeted approach.

“We are going to see clusters and flare-ups in communities amongst people who aren't yet protected,” said Henry.

“So it is a different approach, and it's because we have that really important and effective tool of immunization that allows us to be more focal in our responses.”

Still, the outbreak in the Okanagan is a reminder we are not out of the woods yet on the pandemic. Lower vaccination rates in the province’s north are proving particularly problematic, and it’s heartening to see Opposition BC Liberal MLAs who represent those communities partnering with Health Minister Adrian Dix to hold non-partisan telephone town halls that encourage people to get vaccinated.

For now, B.C. is sticking to its re-opening strategy and removal of mandatory masks.

“I think we need to recognize that being vaccinated not only protects us, but our community is at risk as well,” said Henry.

“And we've seen that when we have high rates in long-term care homes -- that we protect everybody else in that home as well.”

Rob Shaw has spent more than 13 years covering BC politics, now reporting for CHEK News and writing for The Orca. He is the co-author of the national best-selling book A Matter of Confidence, and a regular guest on CBC Radio.

SWIM ON:

- Rob Shaw: BC reporting “only” a $5.5 billion deficit shows just how much has changed during the pandemic.

- It’s no secret there are lower vaccination rates in northern and interior BC. But Dene Moore says the reasons why aren’t as simple as many think.

- B.C’s colonial land policy was an experiment – and a response to the “imaginary boundary” with the United States, says award-winning historian Daniel Marshall.