Over 100 years ago, a medical officer in the City of Victoria became one of the great unsung heroes in British Columbia history.

To combat the rising tide of the (misnamed) Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, he asserted immediate prevention programs and closure of all public venues in the Capital Regional District.

He had good reason. Some 500 million worldwide had apparently contracted the disease, resulting in the deaths of at least 50 million people – vastly more than the total attributed to the First World War.

Masked by symptoms most often associated with a common cold bug (chills, fever, headaches, sore throat, respiratory infection and so forth), the misdiagnosed fever quickly swept the continents into a full-fledged pandemic – and physicians and pathologists in British Columbia were caught in a state of unpreparedness.

From 1918 to 1920, three successive waves of this virulent influenza raged, seemingly originating in China. The Canadian military historian Mark Humphries says that “newly unearthed records confirm that one of the side stories of the war—the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines on World War I's Western Front—may have been the source of the pandemic.”

There is a connection to Vancouver. Humphries’ research “found medical records indicating that more than 3,000 of the 25,000 Chinese Labor Corps workers who were transported across Canada . . . ended up in medical quarantine, many with flu-like symptoms.”

Rather than transport them around Africa, “British officials turned to shipping the laborers to Vancouver on the Canadian West Coast and sending them by train to Halifax on the East Coast, from which they could be sent to Europe.”

Nevertheless, human nature being what it is, mandatory measures soon followed.

At the time, Canada had no centralized government health authority to launch a national defense plan. As a consequence, emergency programs fell to provincial and local municipal authorities who enacted differing responses to the threat.

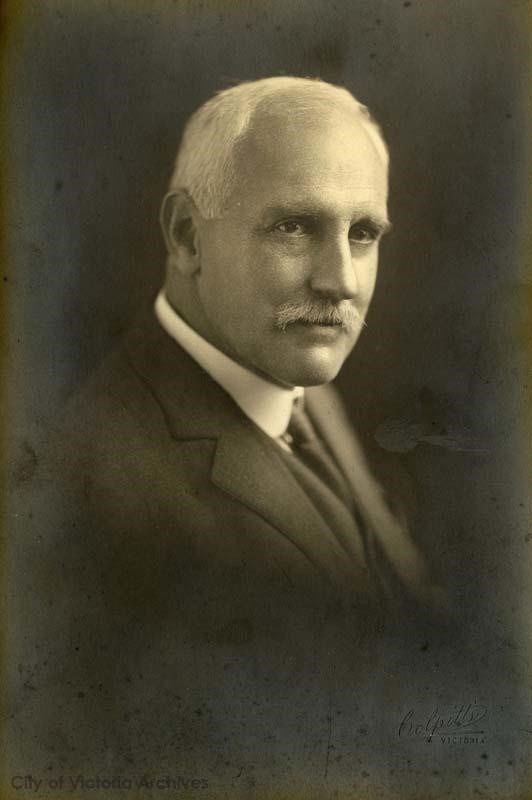

Enter Victoria’s City Health Officer, Dr. Arthur G. Price.

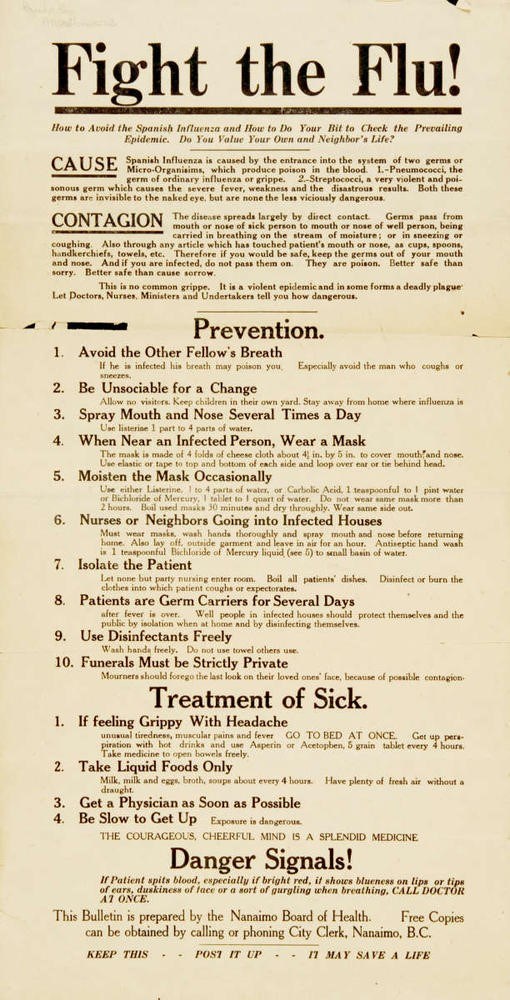

By early October 1918 increasing reports from Canadian cities detailed the death toll of those who had succumbed to the virulent disease; this was the likely impetus for Dr. Price to institute immediate prevention programs in Victoria. A little over 100 years later, official health advisements on curbing the spread of Coronavirus (Covid-19) are fundamentally the same as in 1918: avoid crowds; if you feel ill, self-isolate and get immediate bedrest.

Nevertheless, human nature being what it is, mandatory measures soon followed – not unlike what is occurring in other parts of the world right now. In a Victoria Daily Times article, October 8 1918, entitled Prohibitions of meetings to check spread of germs, the BC Provincial Board of Health issued new regulations to support local community efforts to halt the spread of the contagious disease with “the closing of all places of assembly as a preventative measure against the spread of Spanish influenza.”

The Honourable J. D. MacLean, BC’s Minister of Health & Education (and later Premier) used the Public Health Act to empower a city’s medical health officer to close public spaces at will, enforced by the police.

Apparently Dr. Price had strongly urged a closure ban in Victoria, while Vancouver remained wide open (City will act to check epidemic, October 81918, Daily Colonist, p. 4). Upwards of 100 cases of the influenza had already been reported in Victoria, and so Dr. Price was quick to implement the closure power he had sought over all public and private gathering places. Shortly thereafter, schools, churches, libraries, theatres, colleges, and dance halls were shuttered for a total of 33 days, and community gatherings in general were banned.

In addition to closures and a ban on public gatherings, Price repeatedly issued ongoing advice to maintain good health (diet & exercise), and to steer clear of potential carriers of the disease that might be found coughing and sneezing. Furthermore, if one was exhibiting any of the symptoms themselves, they should immediately go to bed and call a doctor; the first 24 hours were deemed critical to ward off severe pneumonia and potentially encourage an early recovery.

"Wake up! Realize that there is a war on, a war in our very midst, an epidemic of influenza. Do not sneer at the enemy. Do not belittle it by calling it ‘Flu.’ Give it its full name, be serious and realize that the undertakers are busy."

Along with these measures came an extensive regime of disinfection plans for public institutions. In 1918, Dr. Price catalogued a total of 166 Victoria-wide fumigations of “dwellings, hospitals, schools, churches, hotels, stores, offices, and salesrooms.” (Disinfections of this sort were also carried out in the face of other diseases such as smallpox, measles, and diphtheria, among others.)

In Victoria, private businesses took measures to reassure a doubting public, in some cases publicizing that regular disinfections were being undertaken every 24 hours. Some would go further, recommending that local banks should disinfect paper currency every night, though Price rightly stated, “I am afraid they are too prone to rely upon this means of combating the disease.”

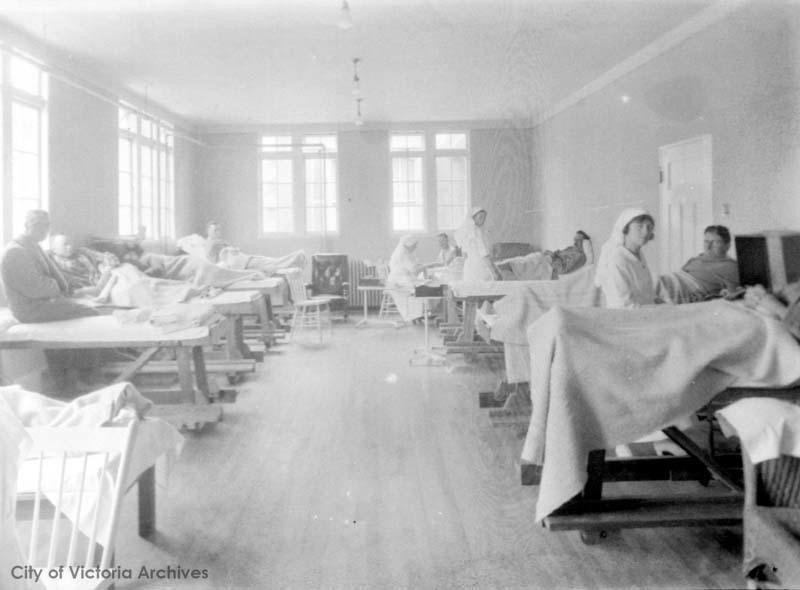

As the contagion spread, Victoria’s hospitals were soon stretched to the limit. Other facilities were quickly prepared where patients could be isolated, including two fire halls. Closing public spaces and banning of community events also impacted the revenues of both the municipal government and commercial enterprises – but apparently the shortfall was in part covered by an increase in liquor sales!

And so just like today, the sheer necessity of getting people back to work, of buying and selling goods and services – in short, of maintaining a healthy economy – placed increasing pressure on medical authorities like Dr. Price to lift the restrictions placed upon Victoria’s business community and public alike. By mid-October, discontent was already rising, when Price refused the local clergy’s request to hold open-air services.

By month’s end, faced with overwhelming public pressure to assemble in large gatherings with the imminent end of the war– Price issued his strongest warning yet:

Wake up! Realize that there is a war on, a war in our very midst, an epidemic of influenza. Do not sneer at the enemy. Do not belittle it by calling it ‘Flu.’ Give it its full name, be serious and realize that the undertakers are busy.

While Price was adamant the ban on public assembly remain in place, mounting pressure from both the religious and business communities continued to increase. Ultimately, some days after armistice was declared on November 11 1918, the month-long ban was rescinded. Fortunately, infections decreased during the remainder of 1918 – but then in January 1919, a third wave of infection rose alarmingly for a brief time. And yet, no comparable closures to Price’s original war on influenza were enacted beyond local schools.

While Victoria experienced a mortality rate of 3.6%, in Vancouver it was an astounding 10%.

What can be made of all this? Perhaps this one telling statistic: in the influenza epidemic of 1918, Victoria fared much better than Vancouver, where similar closures had been delayed for the greater part of the critical month of October. So much so, that while Victoria experienced a mortality rate of 3.6 %, in Vancouver it was an astounding 10%.

As the Vancouver Coastal Health authority noted in 2018, “An estimated 4,000 people died in BC from the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic—about a quarter of those in Vancouver. In today’s numbers that would be about 37,000 deaths for BC and 5,000 for Vancouver.”

In 2020, we’re seeing the same debate over the need to self-isolate, close public gatherings, and possibly even quarantine – yet always balanced alongside the competing need to maintain trade, travel, and the health of local, provincial and national economies. Not much has changed, really.

Are we ready to self-isolate? Are we prepared to change our day-to-day patterns of social engagement? Only time will tell, but while we wait perhaps we might take a moment to give serious consideration to the example set by Dr. Arthur Price over 100 years ago.

As for myself, I think it’s time to wash my hands of all this.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall last wrote the conclusion to The Battle of the Routes - a now-mostly-forgotten political dispute that literally laid the map of modern BC - and almost split it up.

- Amateur historian Rejean Beaulieu has a theory about a more regional understanding of "local" history, and the sites that defined it.

- Michael Layland won the prestigious Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding Scholarly Book on British Columbia with this remarkable work on the study of Vancouver Island's flora and fauna.