In Part 1 of this great untold story, we saw that the present-day Fraser Canyon Route of the transcontinental railway was chosen by Canada over the technically superior Bute Inlet route. Why? Part II provides the answer – a mystery compounded by a long-lost proclamation that officially named Bute Inlet the chosen route, but a document still lost to this day!

Evidence of the Bute Inlet scheme having fallen into disfavour is apparent by Canada’s subsequent application to the Admiralty for particular information on BC’s coastal waters.

The “principal naval officers” who had some familiarity with the province’s harbours were invited to comment in the suitability of nine different terminal points selected on the Mainland.

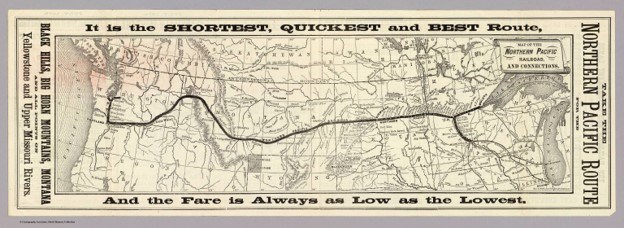

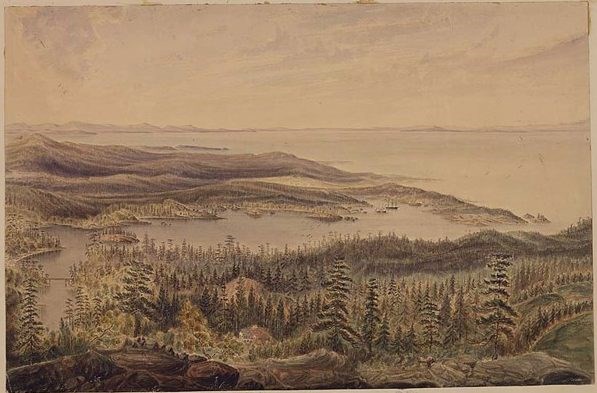

Esquimalt, on Vancouver Island – though it had been selected by Prime Minister Macdonald in 1873 as the Western Terminus – was noticeably excluded from this survey, much to the chagrin of Island supporters. Of essential importance was that the terminus was desired to be as close as possible to Asian trade. The distances from Yokohama, Japan to each individual port-site in BC were compared. Waddington Harbour (Bute Inlet), being so centrally located from either Queen Charlotte or Juan de Fuca Straits, placed last.

The real strategy behind the Bute Inlet Route, of course, was the ultimate plan of bridging the Valdez Group of islands so that Esquimalt could be made the terminus. Esquimalt, since it was located on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, was obviously positioned more favourably than Burrard Inlet for the reception of Asian trade.

Establishing a terminus on Juan de Fuca was not about Victoria’s desire to compete with New Westminster, but the need for the Canadian transcontinental line to successfully challenge the commercial supremacy of its American counterpart.

This goal was fully delineated as early as 1872 by the Honorable Hector L. Langevin, member of the Conservative government at Ottawa. In a reply to a question posed about future railway lands by Amor De Cosmos in the Canadian Parliament, the federal minister acknowledged:

. . . that the Northern Pacific Railway ended at Puget Sound, and the competition which that line will make with the Canadian Pacific Railway renders it desirable to select a terminus that will put us in the best possible position for competition with American railways. If it should be decided that we can cross Seymour Narrows or Johnston’s Straits with a railway train, there can be no doubt that the interests of British Columbia and the Dominion as a whole will be better served by adopting that route.

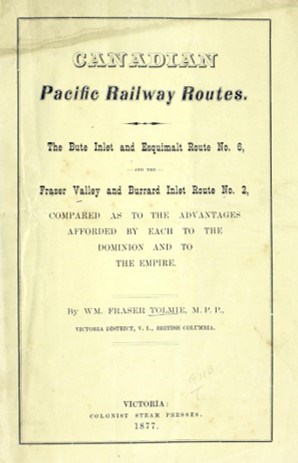

American business interests had also contemplated a possible rail extension to the Strait of Juan de Fuca at either Port Angeles or Holmes Harbour on the eastern shore of Whidbey Island. For others, it was the possible threat of the American government placing guns on the recently ceded San Juan Islands to control maritime traffic entering the Strait. The well-known Hudson’s Bay Company authority, Dr. William Fraser Tolmie, had been quick to point out this possibility in a number of published works.

If the United States were eventually to extend their rail system to Juan de Fuca, Canada would have to follow suit. This option, of course, necessitated the adoption of Bute Inlet No. 6 – the only route that could have possibly allowed for a future Island-Mainland rail connection.

Of the five opinions received from the Admiralty with respect to harbours, four favoured Burrard Inlet; only one declared for Waddington Harbour. Commander Pender was quite direct in his support for Burrard Inlet and discounted the head of Bute Inlet as an “indifferent anchorage.”

Others, such as Admiral Farquhar, qualified their support. Bute Inlet, he believed, to be “more difficult of access” than Burrard or Howe Sound, yet he concluded, “if it were practicable to bridge Seymour Narrows, the railway might be continued to a point on the south or west side of Vancouver [Island].” No Vancouver Island harbours were offered as options.

Admiral Richards was almost quizzical in his support for Burrard Inlet when he replied that “a practicable route, with an inferior water terminus might be preferable to an almost impracticable route attended with enormous expense and a good terminus, such as Burrard Inlet.” Furthermore, some believed that Fraser River No. 2 was simply too close to the United States in the event of hostilities.

The fate of Bute Inlet No. 6 was inextricably tied to Canada’s commitment for an Island railway extension. The fact that Canadian authorities were still hesitant in 1877 to name it as the final route was additional proof that valid considerations were taken into account before the Island extension was finally dismissed. Sanford Fleming admitted as much in his most complete report of that year:

If it be important to carry an unbroken line of railway to one or more of the harbours on the western coast of Vancouver Island, and there is a likelihood that this project will, regardless of cost, hereafter be seriously entertained, then Route No. 6 becomes the only one open for selection.

This point of view was further bolstered by the formidable reputation of Rear Admiral Algernon de Horsey, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Station of Her Majesty’s fleet in Esquimalt. De Horsey was against the selection of Burrard Inlet. He believed that a southern line would be open to possible overland attack from the United States, and therefore, presented a security risk.

Why the Commander-in-Chief was not consulted earlier as part of Fleming’s original enquiries to the Admiralty was, indeed, rather curious – one would have thought his opinion the most important of all.

In a confidential letter of the same year Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken (one of BC’s “Fathers of Confederation”) wrote:

The Canadian Government for some reason or other, mean to ignore it, and to allow as little as possible of its advantages to be made public – preferring to be governed by their own political or other bias in favour of the Fraser River route . . . rather than be guided by the results of scientific explorations of scientific men – the results which lead to the conclusion that Bute Inlet is by far the most advantageous point to touch salt water.

The “scientific men” Helmcken referred to were those such as Marcus Smith, the Resident Engineer, and Rear Admiral de Horsey who supported the Bute Inlet Route. As officials in the most senior positions of authority – in addition to being resident in the new province – were well suited to form an opinion on the best route.

Mind you, De Horsey was also against any immediate bridging of Seymour Narrows and favoured instead the extension of Route No. 6 around the north side of Bute Inlet to Frederick Arm, and then a ferry to Vancouver Island. This apparent compromise to the expensive nature of bridging the Valdez Group was later dismissed by Fleming, and in a lengthy summation of the “Battle of the Routes” he offered his somewhat contradictory, but nevertheless final word:

Burrard Inlet is not so eligible a terminal point as Esquimalt. It cannot be approached from the ocean, except by navigation more or less intricate. Nor can it be reached by large sea-going ships without passing at no great distance from a group of islands [the San Juans, recently ceded to the U.S.] in the possession of a foreign power, which at any time may assume a hostile attitude. . . . Upon carefully reviewing the engineering features of each route, and weighing every commercial consideration, I am forced to the conclusion that . . . . the line to Vancouver Island should, for the present, be rejected, and that the Government should select the route by the Rivers Thompson and Fraser to Burrard Inlet.

The obvious question is what caused Fleming to dismiss the Island link altogether. Previously, he had suggested there was “a likelihood that this project will, regardless of cost, hereafter be seriously entertained.” This was the period in which British Columbia threatened to secede from Canada on no less than three separate occasions, due to the Canadian government’s contravention of the Terms of Union.

In the early days of the secession debate, both Island and Mainland acted in concert for the demand of a proper fulfillment of Article 11 (Railway clause). But once the debate devolved into a contest between sectional interests, the united call for separation as a bargaining tool was effectively split.

Consequently, the Lower Mainland was ready to give up the course of separation once it was assured Burrard Inlet would become the Western terminus of the national dream. Conversely, most of the Island and the Cariboo District continued the secessionist threat, but it no longer had the same degree of influence without the other half of the province in league.

John Robson of New Westminster (MLA and later premier) suggested a surreptitious strategy to Liberal Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie, an effective tactic to quell the separatists of Vancouver Island and the Cariboo. In a letter dated 27 September 1876 (and held by the National Archives of Canada), Robson offered that:

Should this turbulent spirit continue in Victoria, I think a quiet intimation that the Island might be permitted to drop out and resume the position of a Crown Colony, the Mainland of course, remaining to the Confederacy, would operate as a cure. On the mainland a very decided opinion against Victoria bluster about separation is growing up. . . . I have reason to believe that a proposition to let the Island out and establish the seat of Government on the Mainland, from where it should never have been removed, would be regarded very favourably in that section.

The Honorable Robert Beaven (MLA and later premier) referred to Canada’s reappraisal of the BC political climate in a British Colonist article, 20 September 1876, saying they had “discovered the weak points” of support in British Columbia and had worked on these “regional jealousies” to the new province’s disadvantage.

As a result, when Victoria and the Cariboo next cried secession on behalf of a divided province, the visiting federal representative, Governor General Lord Dufferin, simply employed Robson’s advice that had obviously been communicated through Prime Minister Mackenzie. This is not what Victoria and the Cariboo had wanted to hear, but Canada had no intention of losing the Mainland portion of the province – or more critically, access to the Pacific Ocean. On the other hand, if the Island persisted in its temerarious ways…it was expendable.

In short, Vancouver Island risked being reduced to the status of a military colony, not unlike Malta or Gibraltar.

After having confirmed Bute Inlet as the route – while at the same time suggesting the Island portion of the railway would be postponed indefinitely – Lord Dufferin alluded to the Canadian government’s strategy for killing the secessionist threat to Canada. As a veiled warning while in Victoria, the governor-general predicted:

Should hasty counsels and the exhibition of an impracticable spirit throw these arrangements into confusion, interrupt or change our present railway programme, and necessitate any re-arrangement of your political relations, I fear Victoria would be the chief sufferer. . . . a certain number of your fellow-citizens, gentlemen . . . have sought to impress me with the belief that if the Legislature of Canada is not compelled by some means or other, which, however, they do not specify, to make forthwith these seventy miles of [Island] railway, they will be strong enough. . . . to take British Columbia out of Confederation. Well, they certainly won’t be able to do that . . . When once the main line of the Pacific Railway is under way, the whole population of the Mainland would be perfectly contented with the present situation of affairs, and will never dream of detaching their fortunes from those of Her Majesty’s great Dominion.

Nay, I don’t believe that these gentlemen would be able to persuade their fellow citizens of the Island of Vancouver to so violent a course; but granting for the moment that their influence should prevail – what would be the result? British Columbia would still be part and parcel of Canada. The great work of Confederation would not be perceptibly affected, but the proposed line of the Pacific Railway might possibly be deflected to the south. New Westminster would certainly become the capital of the Province. . . . as well as the chief social centre on the Pacific coast. Burrard Inlet would become a great commercial port. . . . Nanaimo would become the principal town on the Island, and Victoria would lapse for many a long year into the condition of a village.

Bute Inlet No. 6 was the superior scheme, and the Canadian government was prepared to decide in its favour, but “the battle of the routes” contest had become so fever-pitched as to threaten Confederation itself – and the loss of access to the Pacific. Canada was prepared to fashion a new political alliance with the Lower Mainland if Island secessionist sentiment continued to grow – and grow it did!

Upon winning the third general election in 1878, Premier George Anthony Walkem (who represented the Cariboo, and the only premier in BC History to return to power from earlier defeat) immediately passed the famous secessionist petition to Queen Victoria which again threatened to pull British Columbia out of Canada. The truly bizarre aspect of this political strategy was the fact that the Governor General’s original instructions were to have publicly proclaimed the Canadian government’s support for the Bute Inlet Route.

David Higgins, later speaker of the BC Legislature, recalled the political events of the day for Historian R. E. Gosnell. Higgins claimed that:

When Lord Dufferin left Ottawa for Victoria it was semi-officially announced in the papers that he was the bearer of a proclamation that would decide the contest in favour of Bute Inlet and Esquimalt. This dispatch, according to Lieutenant Governor [Joseph] Trutch, was sent from Government House to the Provincial Secretary’s office by an official messenger and was handed, so the messenger reported, to the Provincial Secretary. From that day to this the dispatch has not been seen. It never reached the public eye. Who destroyed it if it were destroyed, who secreted it if it were secreted, who lost it if it were lost, will never be known. The parties are all dead. Lord Dufferin always denied all knowledge of its fate, although it was admitted that His Excellency handed the dispatch to the Lieutenant Governor. The Lieutenant Governor said he personally delivered it to the messenger. The Provincial Secretary and the Premier were equally emphatic in asserting that it never came into their hands. Nine years ago Sir Joseph Trutch told the writer that the proclamation adopting the Bute Inlet route was carefully read by him and that he gave it to the messenger himself. He added that the disappearance was as profound a mystery to him as it was to Lord Dufferin.

If Higgins’ story is true, then the Governor General must have been instructed to gauge the strength of the separationist movement and act accordingly.

Canada’s ultimate strategy called for a railway policy that divided the province, and in so doing, conquered the factional interests and secessionist sentiment of the so-called “spoilt child of Confederation.” So to my mind, the renewed call of separation by the Walkem Government caused the railway to be deflected to the south. The Fraser Canyon Route was the expedient means to keep Canada whole from sea to sea. Vancouver Island was not needed as a Western entrepot, nor was the Island essential to the larger Canadian national dream.

Now, just what happened to the proclamation delivered by Lord Dufferin to the BC government, and apparently read by Lieutenant-General Joseph Trutch? Apparently sometime in the 1960s, Inez O’Reilly of Point Ellice House (today’s well-known heritage site) was rearranging the antique furniture of the museum.

One such item was the writing desk of Sir Joseph Trutch that had come into the family’s possession. During this move, a hidden compartment was found in the desk. Here was correspondence apparently from Prime Minister Macdonald, which was subsequently transferred to the BC Archives in Victoria.

When I first heard this story I began to make enquiries – who would not want to know the contents of this letter that compelled Trutch to hide it? But unfortunately, while the letter is somewhere in the province’s archival collections, no one knew exactly where, or in what collection, it had been placed!

This begs the question: could Trutch have not sent the Bute Inlet proclamation? Was it also hidden in the secret compartment of his old writing desk? It’s well known the private interests of Joseph and his brother John Trutch were intimately tied to the Fraser Canyon Route; had Bute Inlet been confirmed it would have spelled the end of their lucrative holdings along the Fraser and Thompson rivers.

While David Higgins wrote that the answer to this mystery “will never be known,” perhaps one day some further historical sleuthing may yet provide the answer!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Don't miss Part 1 of the Battle of the Routes, as Daniel Marshall sets the scene for the great debate over the route.

- Jody Vance on the ignoble end of Don Cherry's TV career, and the end of an era - or two.

- Daniel Marshall on one of the titans of BC historians, Margaret Ormsby.