We are on fire.

British Columbia is burning both literally and figuratively, a tinderbox that has continued to be ignited not just from increased lightening strikes and insufferably high heat, but also culturally as old narratives of the province’s historical unfolding are under increasing fire – along with churches burnt, statues toppled, and even an Indigenous totem torched.

Through it all, the vast majority of our population – both indigenous and non-indigenous – watch in rather silent amazement as the passions of popular, and indeed usually uninformed, protest enflames and divides this province.

Where do we go from here? It is easy to tear down markers of history, but the real question is whether a truly inclusive narrative of this province will continue to be written without the kind of severe backlash that has been seen south of the border.

The Malahat Lookout totem along Vancouver Island’s Trans-Canada Highway was recently set ablaze (and thankfully not consumed). The general determination was this act of vandalism was in direct response to the Canada Day toppling of the Captain James Cook statue in Victoria’s Inner Harbour. The culprit had spray-painted the caption “One Totem – One Statue” near the charred carving, as a seeming statement of retribution.

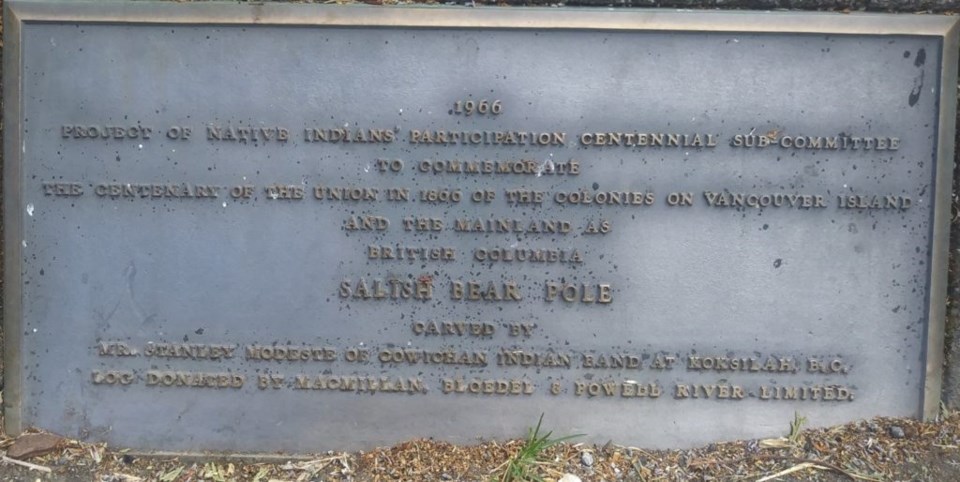

How terribly ironic. The Malahat Lookout pole was originally erected in 1966 (along with two other such poles on the Island) to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Union of the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia in 1866. More ironic still, considering that the totem pole, carved by former Cowichan Chief Stan Modeste, was a “Project of Native Indians’ Participation Centennial Sub-Committee to Commemorate the Centenary” – indeed a marker of British Columbia’s colonial past – as noted on the original bronze plaque that can still to be seen to this day. How times have changed!

The chiefs of southern Vancouver Island have rightly condemned these acts of vandalism in an official statement, knowing that these sorts of flagrant attacks will do little to forward the cause of reconciliation.

As the province continues to grapple with the historic claims of Indigenous nations and their justifiable grievances, especially since joining Canada 150 years ago (the post-Confederation issues of the federal Indian Act, banning of the potlatch, residential schools and unmarked graves among many others), the current penchant to destroy monuments has caused many to become increasingly concerned whether this assists in moving us forward.

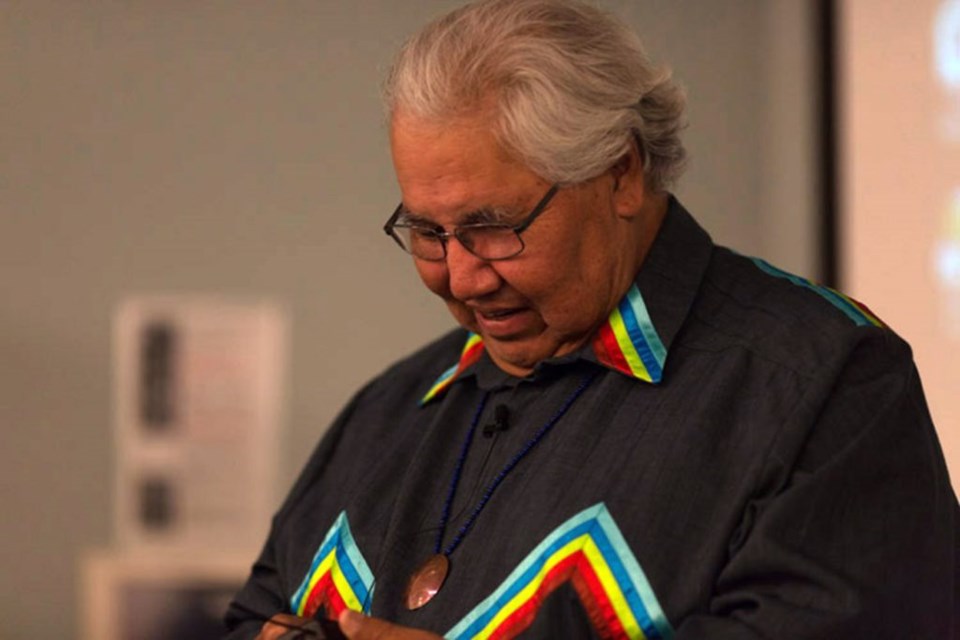

The chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, former Senator Murray Sinclair, forewarned in 2017 that indiscriminate removal of monuments of the past would smack of revenge:

“The problem I have with the overall approach to tearing down statues and buildings [stated Sinclair] is that it is counterproductive . . . because it almost smacks of revenge or smacks of acts of anger, but in reality, what we are trying to do is . . . create more balance in the relationship.”

While in my own way I have worked for the better part of four decades on BC history (including the matters of Indigenous rights, title, and indeed reconciliation), I fear at times that all the good work done towards greater understanding between native and non-native communities might potentially unravel.

While Sinclair’s view seems to have gone largely unnoticed by many members of the public engaged in this kind of hands-on activism, equally disconcerting is the degree to which educated, trained professionals – such as our legal profession – have either fallen silent on the issue, or indeed increasingly have contributed to an increased politicization of history, based on poor historical evidence.

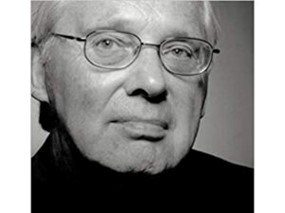

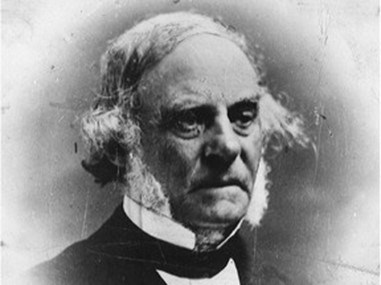

Case in point: last year, during the BC Law Society’s Annual General Meeting, a proposal was introduced by former BC Supreme Court Justice, the late Thomas Berger (seconded by University of Victoria Law Professor Hamar Foster, one of the foremost specialists in BC legal history), to revisit the Law Society’s decision to remove their statue of BC’s first Chief Justice, Sir Matthew Baillie Begbie. It warrants mentioning that Berger has been described as “a great champion of Indigenous peoples and rights,” by MP Jody Wilson-Raybould.

In truth, those calling for a review were perhaps less concerned with the statue’s removal than the fact that the decision was made without consulting the society’s membership, or “without independent historical inquiry,” and more particularly, the belief that the subsequent characterization of Begbie as “racially-prejudiced and an oppressor of the First Nations people” was not supportable from their extensive knowledge of BC history:

“We believe that Begbie’s life was devoted to the rule of law and its equal application to all, and should no longer remain undefended. . . As each generation discovers, no historical figure is without flaws, and this is no doubt true of Chief Justice Begbie. But it would be a mistake for the profession to allow Chief Justice Begbie’s life and work to be dismissed in the way this has been allowed to happen.”

While the proposal to revisit the Law Society’s Begbie decision ultimately received a stunning 75% support from its membership, since that day – now a year and a half later – apparently no further action has been taken, the accepted proposal seemingly ignored. Why is that?

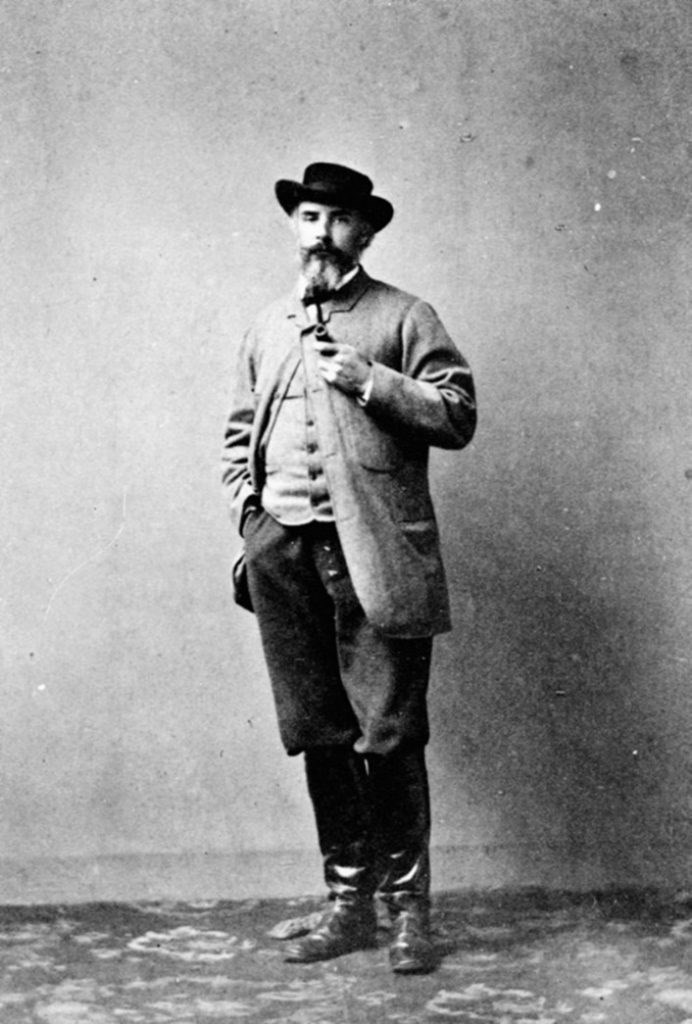

Historically, the creation of British Columbia was definitely not the American experience. This province was founded in opposition to our neighbours to the south and on different principles – “Equality under the Law for All” was in fact British policy enacted locally by Governor James Douglas and indeed implemented by Chief Justice Begbie through the chaos of the British Columbia gold rush.

It is important to remember the context of those times. In a world that seems increasingly divided by racial tension, it’s also worth remembering those who sought asylum here more than 160 years ago, attracted to BC expressly for the guarantee of equality under the law for all.

Among those who escaped persecution in California were the Black Americans welcomed by Governor Douglas. By 1858, the exclusionary policies and legislation of the California state legislature increasingly disenfranchised and discriminated against African-American people.

In the same way, Douglas also extended these rights to Chinese people who relocated from California. Victoria’s Chinatown wasn’t just a colonial outpost – it was a comparative sanctuary for its time.

During Douglas’ time in office Indigenous peoples, too, were guaranteed equality in the colonial courts of law. In his meetings with Indigenous populations in the aftermath of the Fraser Canyon War, Douglas stated:

I had the opportunity of communicating personally with the Native Indian Tribes, who assembled in great numbers at Cayoosh [Lillooet] during my stay. I made them clearly understand that Her Majesty’s Government felt deeply interested in their welfare, and had sent instructions that they should be treated in all respects as Her Majesty’s other subjects; and that the local Magistrates would tend to their complaints, and guard them from wrong … in short, I strove to make them conscious that they were recognized members of the Commonwealth.

So, there is much in the historic record that would cause legal experts such as Berger and Foster to question the BC Law Society’s decision – or lack thereof. And perhaps more extraordinary, legal experts that have contributed so much to the advancement of Indigenous rights and title.

For true reconciliation to work effectively all sides of this complex issue should be heard.

“We have lost a giant,” stated Premier John Horgan with regard to Thomas Berger’s recent death (April 28, 2021). He was right. Let’s hope this British Columbia Day that Berger’s last stand for truth and justice will not be forgotten, and that Chief Justice Begbie may yet have a new trial – this time with a full and complete examination of all the evidence by those remaining legal scholars who have spent the better portion of their lives studying these matters.

For as the BC Law Society’s own Truth & Reconciliation Committee has confirmed, “without truth, justice is not served, healing cannot happen, and there can be no genuine reconciliation.”

Now that’s something to think about this BC Day.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall last investigated a hidden relic from one of mainland BC’s oldest remaining houses.

- Daniel's piece on BC and the pandemic of 1918 - written just days before BC was locked down - is mandatory reading.

- Victoria honoured Mifflin Gibbs, a trailblazer, civil rights activist - and its first black city councillor. Daniel wrote at length about Victoria as a refuge for political exiles.