Last month, we celebrated National Indigenous Day (June 21). The Cowichan Tribes celebrations were attended by close to 1,000 people throughout the day, with many coming out to witness the official return of a remarkable artifact: the ceremonial blanket worn by Chief (Charlie) Tsulpi’multw in London, England, 113 years ago during an audience at Buckingham Palace with King Edward VII – Queen Victoria’s son and successor.

I was delighted to be in attendance, particularly so as I have been researching the life of this amazing Chief for many years.

It was over 20 years ago that I accompanied my good friend and former Cowichan Chief – the late Wes Modeste (Qwustenahun) – to Britain for an extraordinary month-long research trip. We were following in the footsteps of three BC Salish chiefs (two coastal, one from Interior) who had themselves made the journey in 1906 for a personal audience with the King at Buckingham Palace.

Wes was a remarkable ambassador of the Cowichan people:

“He was ahead of his time,” said fellow chief Steven Point and former Lieutenant Governor of BC, “one of our great leaders, upon whose shoulders we stand today.”

Wes and I had been talking for some years about mounting an expedition to seek further historical information on these chiefs in English archives such the Public Record Office at Kew Gardens and the Rhodes House Library in Oxford. These discussions continued until one day, I asked Wes: “When should we go track this history down?” Wes promptly replied, “You white guys got the watches, but we have the time!” We both had a good laugh and in that moment, decided to make the necessary preparations.

Wes was the great grandson of Chief Suhiltun who played a central role in the Indian Rights Association movement of the early 1900s. Suhiltun was not only a hereditary chief, but head chief of the Cowichan Tribes during these years. In the Modeste family’s oral history, it is remembered that their famous ancestor originally intended to make the pilgrimage to Britain, but an accident prevented him from doing so. As such, Suhiltun ultimately appointed Chief Tsulpi’multw to represent the Cowichan people.

During our monthlong stay in Britain we were astounded to find so much information on the epic journey made by these Salish Chiefs to the Imperial capital. Certainly Wes, in continuing the “fight for Native rights” family tradition, would have made his great-grandfather, Chief Suhiltun, proud.

During our ongoing investigations, we discovered how Tsulpi’multw’s long life spanned the generations. As a young man he met Governor James Douglas, who had visited Cowichan Bay aboard the HMS Hecate when the colonial government promised to make payment for lands acquired for non-Native settlement. This unfulfilled promise became the motivation for Tsulpi’multw’s central and leading role in the early fight for Indigenous rights movement in BC during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1906, along with Chiefs Kayapálanexw (Capilano of Squamish) and David Basil (Bonaparte Band, Secwépemc – near Ashcroft), Tsulpi’multw set off to meet the King. This delegation of three chiefs and their Interpreter (Simon Pierre of Katzie) made the great journey on behalf of all BC First Nations, after having appealed in vain to the BC and Canadian governments for proper redress.

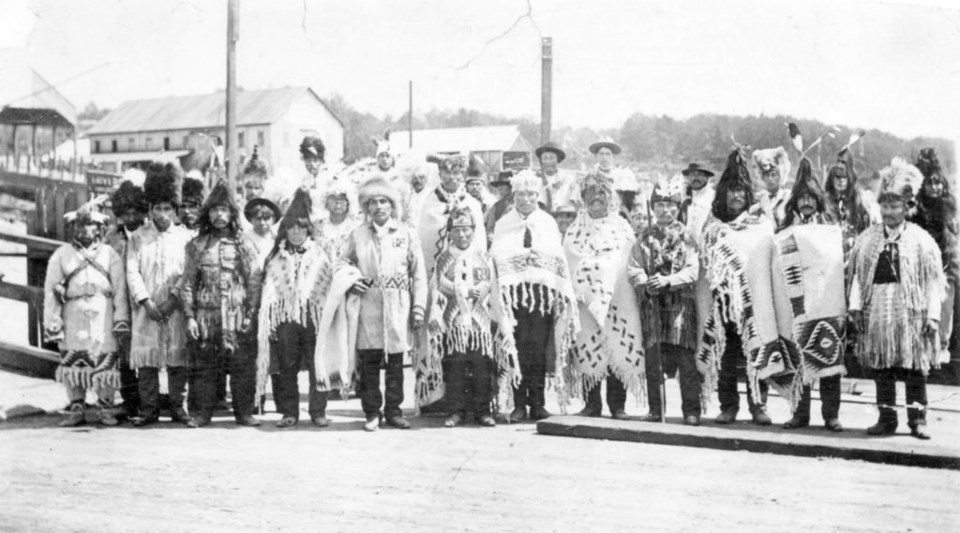

Before their departure, a large parade of Indigenous leaders and non-Native allies was held in Vancouver, a large Native brass band playing as they embarked on a steam train that whistled them across the continent before a long sea voyage to Britain.

While waiting some two weeks in London to present their grievances to the King (apparently away on a hunting trip), the chiefs could be seen walking the streets of London – Tsulpi’multw often wearing his ceremonial blanket – as they toured such places as Westminster Abbey, the Tower of London, and even Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum!

With the King’s delay, Imperial authorities privately hoped that they would simply return to Canada – but Chief Kayapálanexw informed them that they were not going anywhere until they met the King, and had sufficient resources to wait it out at least two years.

As BC colonial representatives had always conducted their business in the name of Queen Victoria – the “Great White Mother” – it was deemed appropriate to go over the heads of the BC and Canadian governments and appeal directly to the monarch. London’s Daily Telegraph of 14 August 1906 reported the crucial moment: “Fortune has crowned the mission of the Red Indian chiefs now visiting London . . . and the Indians forthwith prepared themselves for presentation to the ‘Great White Chief.’”

Kayapálanexw recorded years later how Tsulpi’multw was captivated by their entrance down the red-carpeted rooms of Buckingham Palace, and particularly entranced by the mirror-lined ceiling in the great room where they met the King and Queen.

The 1906 trip brought much attention to the outstanding issue of Indigenous title and the plight of BC’s First Nations – it was a public relations success and this initiative was soon followed by the game-changing “Cowichan Petition of 1909,” the first such legal document prepared by BC First Nations that made reference to the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the assertion that Aboriginal title had yet to be extinguished through Treaty-making.

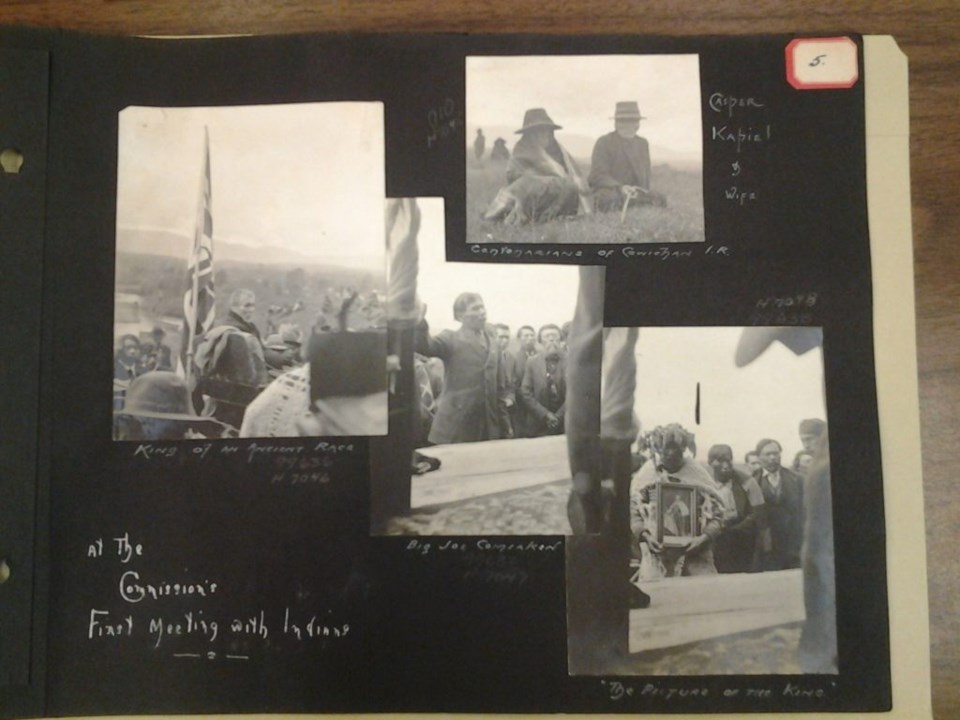

The Cowichan Petition subsequently led the British Colonial Office to put political pressure on both the BC and Canadian governments to address the outstanding question of the rights of BC’s Indigenous people. A Royal Commission on Indian Affairs (known as the McKenna-McBride Commission, 1913-16) was subsequently struck. It eventually toured the entire province, but made its very first inquiries with the Cowichan Nation who had taken such a leading role.

After the death of Kayapálanexw, Chief Tsulpi’multw continued the fight for Indigenous rights well into old age with subsequent trips to both Ottawa, where he met Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, and London (in company with Kayapálanexw’s son Matthias). The Old Obelisk at Mount Tzouhalem in the Cowichan Valley marks not only the final resting place of this great chief, but was originally erected to commemorate his 1906 trip to London and the subsequent and tireless work undertaken by Tsulpi’multw to defend and advance the rights of the Indigenous people of BC. He apparently lived to be 110 years old.

The National Indigenous Day celebrations were particularly special this year not only for the remembrance of this indefatigable leader, but also in that many of his descendants were in attendance, his great grandson Perry George paying tribute to his ancestor by wearing the returned blanket that has been safely kept by UBC’s Museum of Anthropology these last many years.

And with the ceremonial blanket now in the process of being returned to the Cowichan peoples it becomes a compelling reminder to current generations, both native and non-native, that the work undertaken by Chief Tsulpi’multw is unfinished.

Governor Douglas’s promise remains unfulfilled 157 years later – and that sure seems like a long time to wait.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.