As an historian living alongside the great Strait of Juan de Fuca in Victoria, this amazing passageway – surely one of the great waterways of the world – has kept me in rapt attention for years.

Whether strolling along the foreshore viewing the magnificent Olympic Mountains or scaling the heights of Beacon Hill, thoughts of early explorations abound: the Spanish, British and American ships that plied these waters through ancient Indigenous lands, and the Juan de Fuca legend itself: a 16th century tale that foretold of a “Land…rich of Gold, Silver, Pearle, and other things like Nova Spania.”

I find it fascinating that centuries later, goldseekers travelling up the coast from San Francisco in 1858, would have sailed directly by a large rock spire, today called De Fuca’s Pillar, at the entrance to the straits. Take a look at this extraordinary landmark, in fact, a rock spire spoken of in Michael Lok’s centuries-old account of the Greek pilot’s voyage, and right in our own backyard!

So much human history has been compressed into this ocean corridor – an historian’s playground of the imagination – but perhaps less known for producing some of the most amazing natural phenomena to this very day. What is that you ask? A spectacular light show seen every summer, when the conditions are just right for periodic mirages that visually shapeshift the natural order of things.

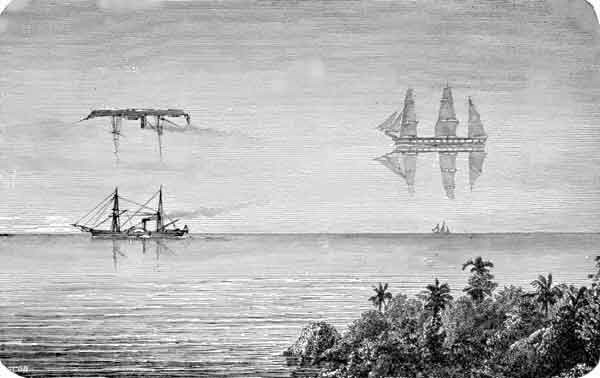

The Straits of Georgia, Juan de Fuca & Puget Sound are the best areas for viewing “superior mirages,” in which objects near the surface are expanded or projected upwards, occasionally even being inverted. An example over the Georgia Strait is shown here, with an elevated, inverted boat and enhanced mountains behind. (Courtesy Bestweather.blogspot.com)

I have always wondered why these curiosities don’t receive more public attention, especially considering they had so enchanted observers in the past! Apparently Beacon Hill was, and still is, the favoured viewpoint for the “Fata Morgana.” Newspaper reports of the 19th century from Victoria record these mirages as “indescribably grand” and “far excelled anything of the kind we had ever before witnessed.” Race Rocks lighthouse at times was seemingly “duplicated on different portions of the reef” and on another occasion “a large vessel with all sail set was speeding towards the straits, and high up in the clouds appeared another vessel, a counterpart of the one on the water, upside down!”

Indeed, one account from the Daily Colonist, 6 June 1868, recorded the “beautiful phenomenon” from atop Beacon Hill:

The sea was calm and the atmosphere hot, a large vessel was under full sail down the Straits, when suddenly it changed its appearance; a large black object was then seen floating in the air directly over the mast-head, from which gradually descended sails and masts, until they reached the mast-head of the vessel underneath; after floating about for some time faded away, and again reappeared with double refraction. Two ships in the air and one underneath poised exactly one above the other. . . The hills of Sooke became inverted over the light-house, and as if thrown across to the opposite shore, at least 100 feet in the air . . . . thus forming a natural and beautiful bridge from Sooke to the Olympian range. . . . the whole scene constantly changing and forming phantasies as strange as they are beyond description. It was a wild and weird scene, which would not be often witnessed in a life time.

In the days before radio, television and the internet, such contorted landscapes and illusory “phantom ships” were seen up and down the Pacific Slope – did we humans simply spend more time recreating outside than today?

By the end of the 19th century these “castles in the air” took on increasingly more complex mirage forms – that of cities floating in the air. Audiences were captivated, and the emergent tourism industry took note.

So, the mirages of Juan de Fuca Strait got me thinking of phantoms in the air, and my own recent quest to discover more. In The Spell of the Yukon (1907) by Robert Service, the celebrated bard writes of the trail one sometimes takes: “And sometimes it leads to the desert, and the tongue swells out of the mouth, And you stagger blind to the mirage, to die in the mocking drouth.” I hope I have better luck!

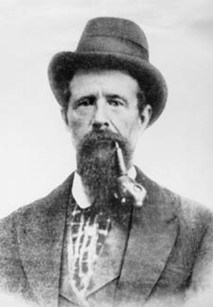

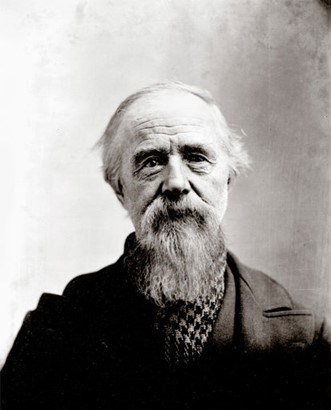

Probably the best known mirage story of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a wonderous tale told by “Professor” Richard Willoughby (1832-1902), a transnational gold seeker who had participated in the California, British Columbia, and subsequently Alaskan/Yukon rushes.

Willoughby, an “Indian-fighter” from Missouri and later a “Texas Cowboy” in the punitive raids into Mexico, took the Pacific Coast Inland routes, via the Columbia and Okanagan river systems, to British Columbia in 1858.

Of his journey from California to British Columbia, Willoughby recalled the military-like precision with which their party proceeded towards the Fraser River, their intrusion (along with thousands of others), leading to the “Indian Wars” of that year in Washington Territory.

Willoughby had been involved in a battle at McLoughlin Canyon, just south of the border, at the same time that the Fraser River War was unfolding north of the 49th parallel. He eventually mined for gold along the Fraser, the Cariboo and elsewhere in British Columbia before eventually making his way up to Alaska, where today a street and island are named after him – along with a creek in BC.

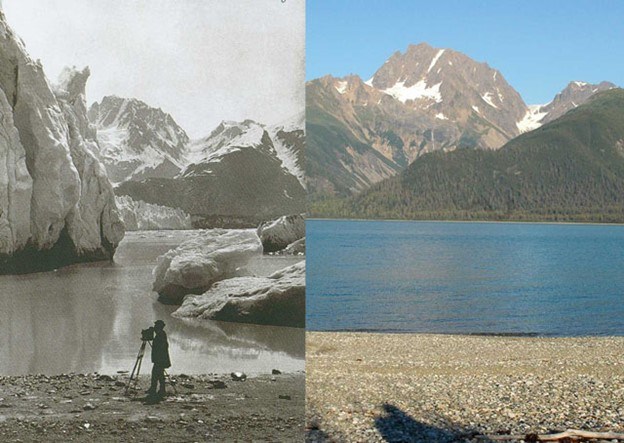

In about 1885, he promoted the astounding claim to have photographed a “phantom city” above the Muir Glacier in Alaska.

While Anthropologist Franz Boas had photographed a number of mirages on his trip to Baffin Island in 1883-84, Willoughby’s 1885 claims were of a far greater magnitude – a substantial fata morgana, or “the Silent City” found hovering over the icefields in what is today Glacier Bay National Park.

The Alaskan News, 26 July 1888, was just one of many to report Willoughby’s incredible discovery.

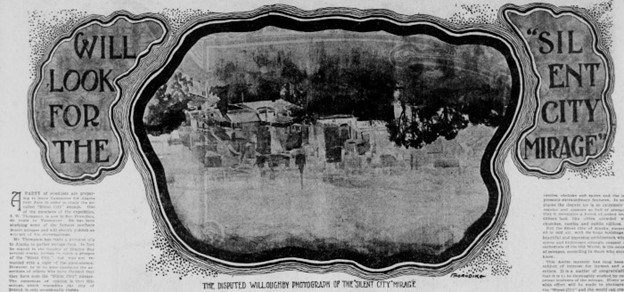

Dick Willoughby succeeded in securing two excellent negatives of the wonderful city reflected on the glassy surface of the Pacific glacier. He photographed it from two different positions, and there obtained one view looking across the main streets and the other looking down them. The city, or mirage, appears just after the change of the moon in June, and just as the sun is setting in the evening behind the Fairweather range and while the moon is climbing the heavens in the east.

Dick first became aware of the appearance of this city of the icebergs through the Indians, and has since for a number of years past with his own eyes seen it appear and disappear . . . Each succeeding year he has noted a rapid growth to the city, and one building, which was but a foundation four years ago, is now a massive structure seven stories high. Dick attempted to photograph it last year, but only succeeded in getting a blurred negative; however, this year, the atmosphere being more favourable, his attempt resulted in two clear negatives.

“Various were the conjectures as to the locality from which the shadow was evolved,” wrote the Colonist, 17 October 1889. Victoria, Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco were initially surmised as the basis for the glimmering mirage, and some went further suggesting that “the mysterious city was the phantom of Montreal.”

While increasing news of the Silent City spread throughout North America, Willoughby commenced selling copies of his now famous photograph in addition to guided tours of the glacier. By 1897, even Popular Science magazine published a full account.

As early tourists to Alaska started in search for the mysterious apparition (with Willoughby’s guidance), soon the scientific community began to question his claims. The San Francisco Call alerted its readership, 28 April 1901, that “a party of scientists” would soon leave Vancouver to study the Silent City Mirage.

More than a dozen years had transpired since Willoughby had first proclaimed the Silent City, and as the years went by the tale grew is size and detail with many subsequent visitors also claiming to have seen the remarkable vision. For instance, the Colonist recorded, 7 February 1901, that a Mrs. C. S. Longstreet, a “well-known writer and traveler” had visited Alaska in 1899 with the hope of catching a glimpse:

“I was with a party crossing Lake Lebarge. We were going slowly, and had plenty of time to look about us. Suddenly something loomed up ahead of us, and there we saw rising from the mountains a misty picture of an ancient city. Each object was perfectly outlined. The sight was too vivid to doubt of its reality.”

Increasing numbers of tourists continued to travel to Alaska to see the fabled sight, and apparently cruise ship passengers were still searching for the phantom city as late as 1928.

There seemed to be no stopping the public’s fascination with Willoughby’s story; that is, until W.G. Stuart, an employee of Wells, Fargo & Company, happened to see a copy of the picture in a Montgomery Street shop in San Francisco.

He recognized the city at once as Bristol, England, where he had formerly been clerk under the United States Consul. While the reflections of Victoria, Seattle, Portland, or San Francisco had seemed possible candidates for Willoughby’s mirage, even for an incredulous public, Bristol was deemed too far away – indeed, on the other side of the world! And soon, the anomalies of Willoughby’s story began to unravel.

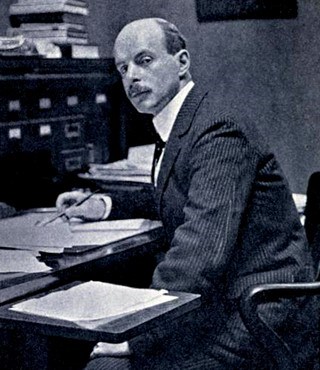

Interestingly, the last word on this story is told by “one of the world’s foremost mining engineers” who retired to Victoria, and as historian was to become a president of the British Columbia Historical Association (the precursor to today’s BC Historical Federation).

T. A. Rickard’s last book was a semiautobiographical work called Autumn Leaves (1948) in which he tells of travelling to Alaska and investigating the Silent City conundrum.

I was shown an alleged photograph of the so-called Silent City said to have been seen above the Muir glacier. Photographic prints of this marvel were sold to tourists by Richard Willoughby, known locally as ‘the Professor’. I scented a pseudo scientific fake and took the trouble to expose it. The fraud was done skilfully, and many were fooled by it for many years. Willoughby asserted that he had seen this vision of a modern city with church towers, office buildings, and people on the streets in the air above the glacier. He had photographed it on June 21, 1885. And if it could be photographed, it must have been there, of course. The Professor had a white beard and a resonant voice. He was impressive. The leading citizens of Juneau decided that the story was a drawing-card for tourists, and they encouraged him to place his prints on sale. When I examined one of them, I noted that it showed trees that were leafless, which seemed inconsistent with what one expects in June. The negative was on glass, and it did not fit Willoughby's plate-holder, nor could the photograph have been taken by his lens, which was meant for portraits. These facts I learned from a friend, who was loath to expose the Professor, because the deception harmed nobody and it brought tourists to Juneau.

Rickard next revealed that in 1887 “the Professor had happened to be in Victoria, on Vancouver Island” and while here bought a “photographic outfit, which included a box of glass plates.” Among them was one “poorly developed picture of the city of Bristol.”

“It reminded him probably of a mirage and the optical effects to be seen above a glacier on a warm day,” snitched Rickard, and there “arose the idea of a photograph of a silent city vibrating in the tenuous air of Glacier Bay.”

To clinch the evidence, Rickard contacted his cousin near Bristol, to confirm the exact date of Willoughby’s glass plate photograph did not correspond to Silent City’s discovery date.

“Some people like to be fooled by alleged marvels” declared Rickard, “perhaps I should not have interfered with their enjoyment.” Or as Mark Twain said, “Reality can be beaten with enough imagination.”

I can’t help seeing Willoughby right now, sailing out the strait past de Fuca’s pillar, camera in hand, traveling north, and marveling over an inspiring mirage cast by a glacier of the Olympic Peninsula. Perhaps our own tourism industry should take note.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall last spun an equally mysterious tale with the story of a stolen "Haida" treasure - which apparently brought disaster on all who possessed it.

- Bob Price cautions modern mountain travelers on the very real threat of avalanches - and how to be prepared.

- Mike Robinson on one of the easiest, smallest, and rewarding acts of reconciliation - learning the Indigenous names for the places you live and love to visit.