Some years ago, I started a mission of exploration.

I headed to the small community of Seymour Arm (previously Ogdenville, Seymour City) in Shuswap Lake country in search of a trail my great-great-great Uncle William built during the Big Bend gold rush of 1865-66 for the Crown Colony of British Columbia.

For years, I wondered whether it still existed. The trailhead apparently started at the instant gold rush town of Seymour City, crossing the Monashee Mountains to the Columbia River. I was also determined to find out more about this particular gold rush, it seeming to have escaped larger notice.

I not only found the trail itself, but the significant impact it had on opening the Interior for early non-Native settlement.

Indeed, as I was to discover, the forgotten Big Bend gold flurry was the signal event that reshaped the Interior grasslands of British Columbia – promoted by a Colonial Office official parachuted into B.C. to kickstart the failing economy.

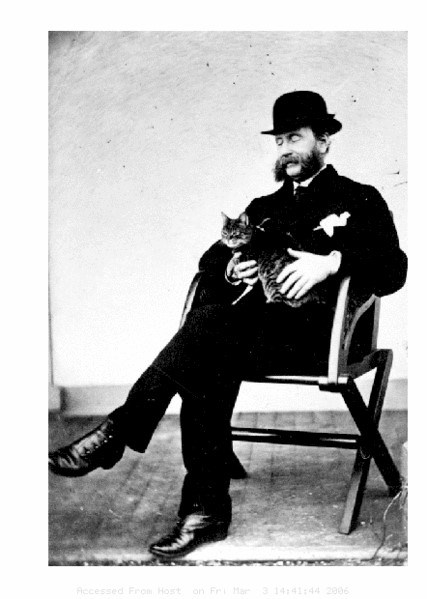

The remarkable story of Arthur Nonus Birch (later Sir Arthur) is not only a tale worth telling, but one that would leave its substantial mark on the province.

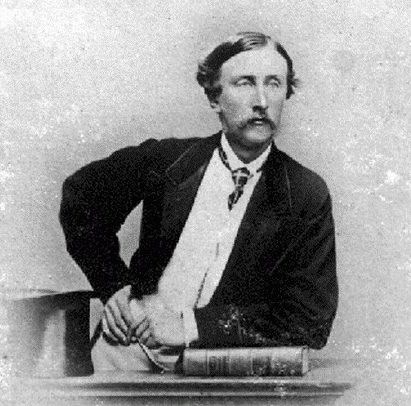

A career civil servant, impeccably well-connected within Colonial Office circles in London, Birch came to British Columbia in 1864 with newly-appointed Governor Frederick Seymour, the successor to James Douglas.

The Colonial Office List for 1877 reveals Birch intimately knew and worked for some of the highest authorities in imperial governance, including four separate cabinet members who had been secretary of state for the colonies. Birch’s brother, the Reverend H.M. Birch, had been tutor to the Prince of Wales.

With respect to the new Governor of British Columbia, Birch recalled:

Fred Seymour, who I knew as Governor of Honduras, a brother of General Sir Francis Seymour, was appointed first Governor, and specially asked that I should be allowed to leave from the Colonial Office to go out with him and start the new Government on Downing Street lines.

Before leaving for British Columbia, Birch had co-edited The Colonial Office List for 1863 – an annual publication that included the “Rules and Regulations for Her Majesty’s Colonial Service” – thus testifying to his expertise in such matters. So it was no surprise that Birch would become acting Governor during Seymour’s absence.

But to ensure this transfer of power, Seymour appointed Birch the Colonial Secretary – considered the highest official within the B.C. executive council –giving him all responsibility and authority for the administration of the colony.

Prior to the Big Bend rush, there had been significant gold strikes in the vicinity of Rock Creek, which compelled Governor Douglas to construct a viable trail from Hope to the Similkameen District (“The Dewdney Trail”), to prevent the gold from being diverted south of the 49th parallel – always a problem for colonial authorities.

In 1864, the year of his arrival, Arthur Birch commanded an official exploratory party to the Kootenay region to see firsthand the new gold diggings of Wild Horse Creek, but also was particularly concerned to establish an all-British route to these mines. In the Colonial Secretary’s unpublished reminiscences, the threat of American annexation of this new gold district once again demanded action:

We received Californian papers reporting great gold discoveries on the spurs of the Rockies in the Kootenay district. As far as we could gather from old maps, the country described was in British territory. The rude maps of those days made it very difficult to decide satisfactorily. . . [but we] became anxious, with the idea that if the reported mines were in or near the boundary, Americans would annex them. . . . I suggested that, as I had been a prisoner in New Westminster for some four months, I should undertake a journey of discovery . . .

As with the Fraser Rush of 1858, American interests were again threatening to siphon off the lucrative trade south of the border – and Birch’s expedition confirmed that the only way to get there was through the United States.

At this juncture in B.C.’s development, no practicable British route existed to the Columbia River region. This became the driving necessity of the Seymour/Birch administration.

When the Official Kootenay Expedition returned, Birch and his exploring party delivered 75 pounds of gold dust into the treasury, the colonial revenue quickly collected from the Wild Horse gold fields. In Birch’s words: “We were the first Gold Escort direct from the Rocky Mountains to the seaboard of the Colony.”

The delivery of such incredible wealth immediately drew the attention of both colonial and imperial authorities, along with the local press. The British Colonist published the entire report and agreed with the need for an all-British route.

The trail by way of Rock Creek is not the one which will enable the traders of Vancouver Island and British Columbia to compete with their American neighbors. . . . we could not, with our present routes, however improved, place goods in the Kootenay mines anything like so cheap as the packers and traders from Oregon. It devolves, therefore, on the Government of the neighboring colony to discover if possible a line of transit that will reduce the land travel nearly one-half.

Ultimately, as gold discoveries moved from the Wild Horse diggings towards the Big Bend, he favoured connecting the Columbia gold fields via Kamloops and Shuswap.

The government was compelled to plot an all-British route to the mines via Kamloops and Shuswap, and open the agricultural capabilities of the Interior to supply the gold fields, instead of continuing to import everything from the United States.

If the colony was to survive and thwart American expansion, land settlement had to occur quickly.

The gold colony reached its critical moment.

Birch subsequently became acting governor during Seymour’s lengthy absence from British Columbia, and during this time Birch both largely instigated and authorized all public works connected with this new gold rush. Writing to the Colonial Office, Birch confirmed:

I have the honor to report that extensive Gold fields have been discovered on that portion of the Columbia River commonly known as ‘Big Bend’. . . . The excitement prevailing in California and throughout the neighbouring Territory convinced me of the necessity of opening communication with these mines without delay and in time to enable the Merchants to throw in supplies before the ‘rush’ of miners fairly commenced.

Thus, a new gold rush mania had swept British Columbia, with the local press trumpeting upwards of 10,000 gold seekers anticipated in the summer of 1865. The British Columbian newspaper in January 1866 proclaimed: “The Big Bend diggings are the all absorbing theme. Everybody talks about them, thinks about them, dreams about them, and every available human being is going to them at the earliest possible moment.”

The general mania that propelled the colonial government both secured and built the new “Big Bend highway” that branched off the better-known Cariboo Road at Cache Creek to Savona, then by steamship through the Kamloops and Shuswap territories, ultimately to the instant town of Seymour City. From here a trail was then constructed to the Columbia, with the added possibility of connecting the whole road system not only to the Fraser network, but with Canada itself.

As with much of my ground-truthing historical research, serendipity would strike.

Having made it to the little community of ‘Seymour City’, I surveyed the landscape for clues to its gold rush past.

The pilings remained for the wharf constructed to accommodate the arrival of steamships – but where was the trail?

I asked questions at the local pub, but no one seemed to know – until I met a third-generation trapper who knew the country intimately.

He was rather shocked to discover my interest, quickly rolled out his maps, and pointing with a finger directed me on how best to find the original trail bed. Apparently, he was the only remaining person in Seymour Arm to know of its existence!

The very next day, a colleague and I bushwhacked off the road and quickly found ourselves standing on a remnant of this long-forgotten route!

Though the Big Bend rivaled the better-known Cariboo gold fields only for a brief period, this flurry of activity was crucial.

It brought increasing awareness of the absolute importance of fostering agricultural settlement to undercut American interests. From this moment, the ranching industry took off, while at the same time becoming the impetus for reducing the size of early Kamloops and Shuswap Indian reserves. The validity of these reductions are still being argued in court today.

From the colonial perspective, non-native settlement had been slow, as gold rushes were notorious for quickly booming and suddenly busting. But with Birch, the progress of the colony had seemingly been jump-started and “Downing Street lines” considered it all “a very excellent performance for a Colony 8 years old.”

In my opinion, the significance of this gold rush has not been given the attention it deserves. The colonial administration was under huge pressure to succeed (as previously under Douglas), and building roads to new goldfields continued, even at the risk of incurring further debt.

The alternative, of course, were the thousands of potential Americans ready to assert their own sovereignty north of the 49th parallel if the British had not done so.

As for the question of Indigenous sovereignty – that remains to this day.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.