Given the recent BC municipal elections, it seems appropriate to remember the extraordinary multicultural roots of our civic politics in this province before joining Canada in 1871.

Recently, Victoria honoured the contributions of Mifflin Wistar Gibbs by naming a study room in its newest public library after the former city councillor (1866 – 1869). The city also proclaimed November 19 “Mifflin Wistar Gibbs Day” in honour of Gibbs becoming the first black person elected to public office in British Columbia.

But there is far more to this story than a brief library announcement!

By 1858, the exclusionary policies and legislation of the California state legislature increasingly disenfranchised and discriminated against Afro-American people. Meetings were held in San Francisco where it was decided to leave and relocate for freedom’s sake – either to Sonora, Mexico; or Vancouver Island.

A delegation was appointed to meet with Governor James Douglas (a Scottish West Indian married to an Irish Cree woman) who welcomed these persecuted peoples and extended to them full rights of citizenship and equality under the law.

"We are fully convinced that the continued aim of the spirit and policy of our mother country, is to oppress, degrade, and outrage us. We have, therefore, determined to seek asylum in the land of strangers, from oppression, prejudice and relentless persecution that have pursued us for more than two centuries in this our mother country.

Therefore, a delegation having been sent to Vancouver’s Island, a place which had unfolded to us in our darkest hour, the prospect of a bright future; to this place of British possession, the delegation . . . have fulfilled and rendered the most flattering accounts…”

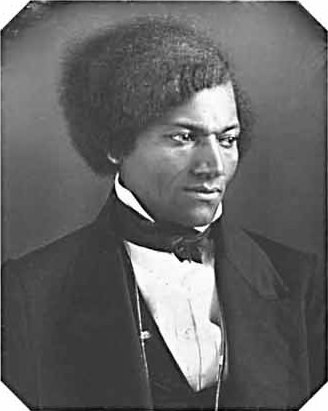

With Douglas’ guarantee, these Black Californians moved north. Among them was the civil rights activist Mifflin Gibbs, who had commenced his advocacy in the eastern U.S. along with the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Gibbs left for California sometime in 1849-50, and recorded of his time in San Francisco that “they were ostracized, assaulted without redress, disenfranchised and denied their oath in a court of justice.”

By comparison, Gibbs viewed British Columbia as a land of freedom. Writing of their arrival in Victoria, Gibbs stated:

"We received a warm welcome from the Governor [Douglas] and other officials of the colony, which was cheering. We had no complaint as to business patronage in the State of California, but there was ever present that spectre of oath denial and disenfranchisement; the disheartening consciousness that while our existence was tolerated, we were powerless to appeal to law for the protection of life or property when assailed.

British Columbia offered and gave protection to both, and equality of political privileges. I cannot describe with what joy we hailed the opportunity to enjoy that liberty under the ‘British Lion’ denied us beneath the pinions of the American Eagle.

Three or four hundred colored men from California and other States, with their families, settled in Victoria, drawn thither by the two-fold inducement – gold discovery and the assurance of enjoying impartiality the benefits of constitutional liberty.

They built or bought homes and other property, and by industry and character vastly improved their condition and were the recipients of respect and esteem from the community."

The reception received by the Black Americans in 1858 was reminiscent of Gibbs’ mentor Douglass, who had visited Britain and Ireland in the previous decade. Arriving in Ireland in 1845, Douglass was struck by the seeming racial colour-blindness he encountered:

"I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab – I am seated beside white people – I reach the hotel – I enter the same door – I am shown into the same parlour – I dine at the same table – and no one is offended…I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with kindness and deference paid to white people.

When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ‘We don’t allow n*****s in here!’"

While in Britain in 1846, Douglass met Thomas Clarkson, one of the last living British Abolitionists (he died later that year) who had assisted in persuading Parliament to abolish slavery in Great Britain and its colonies. Undoubtedly, the positive reception Douglass received in Britain would have been well known to Mifflin Gibbs, and a further incentive to relocate to the New El Dorado of the north.

While it must be acknowledged that there was racial prejudice in Victoria through the early gold rush period, much of this anti-Black sentiment left with American residents returning to the U.S. at the commencement of the American Civil War.

As proof, Gibbs was subsequently elected in 1866 to Victoria City Council as the first Black councillor representing James Bay – and served for a time as the acting mayor. He also was a delegate to the “Yale Convention” organized by Amor De Cosmos to discuss B.C.’s entry into the Canadian Confederation.

With assistance in early legal training in Victoria, Gibbs later returned south of the border after the Civil War, and in Arkansas became the first African-American judge in the United States.

James Douglas’ final word regarding the black people of California applies to other ethnic and racial minorities that also fled north to escape persecution.

“I am glad that Her Majesty’s Government…generously grants, within the Colony of Vancouver’s Island, a refuge for political exiles, provided they yield obedience to the Laws, and avoid public scandals, and lead quiet and honest lives.”

Certainly, the attraction of British Columbia was gold, but for those outside full American citizenship, British Columbia represented much more than the potential for economic gain.

The New El Dorado also represented gains in political and social well-being, as opposed to the legislated policies of exclusion found south of the international divide.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.