This week, the Supreme Court ruled that Canadians living abroad – expats – have the right to vote in federal elections, no matter how long they’ve lived outside the country.

Previously, there was a five-year window – if you didn’t primarily live in the country for five years, you weren’t allowed to vote.

Now, that’s changed. Nobody could object to “citizens have the right to vote” in theory – but when in comes to Canadian expats, it might be much more difficult in practice.

There are several problems.

First, logistics. We don’t live in a presidential system – you knew that, but consider what it means for voting.

It’s one thing for (say) French expats to vote in their presidential elections; where you live doesn’t matter – it’s a straightforward case of most votes wins, period. It’s a little more complicated in the United States, where the Electoral College means your voting state matters enormously.

In a parliamentary system, it’s even more complex.

By definition, you’re voting for a local candidate. Yes, your final decision can depend on how you feel about the party leaders – and yes, in many cases that’s probably the decisive – or even only – factor. But the bottom line is what’s actually on your ballot’s bottom line: your local candidates.

Nobody in British Columbia can vote for or against Justin Trudeau – or Andrew Scheer, for that matter.

So what do we do with expats? The Trudeau government’s solution is to take expats’ last known Canadian address and essentially give them a legacy vote in that riding. Sounds simple, but you don’t have to think too long before running across difficult questions. For example, what happens if you leave Canada before you’re old enough to vote – do you get to vote in your parents’ last address? Why?

The second problem is a little more esoteric. What, precisely, is an expat voting for?

Ask them, and they’ll tell you: it’s essentially an expression of their values – which is wonderful, but they don’t have to live with them.

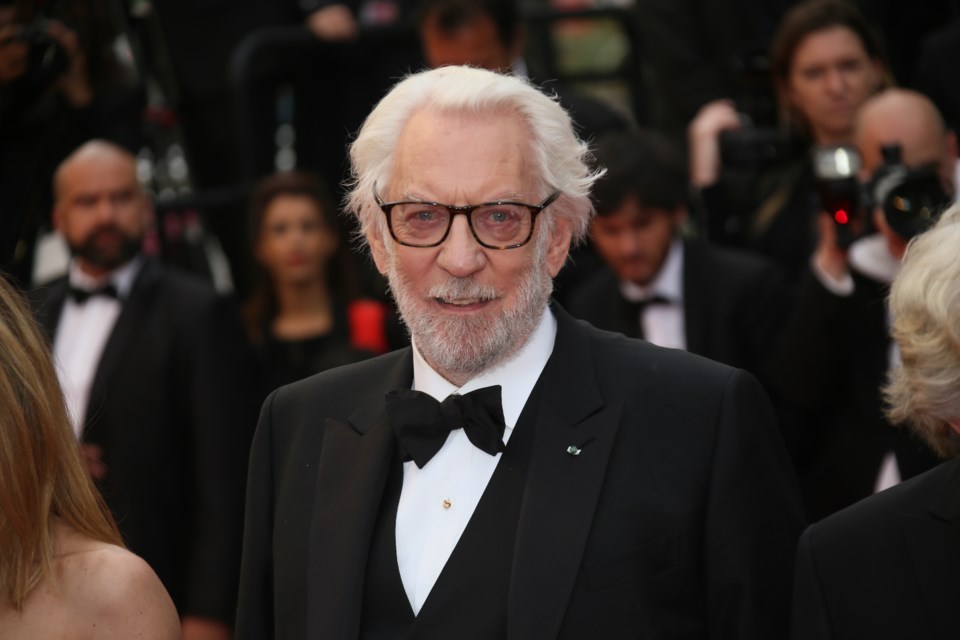

Famously, Donald Sutherland wrote (quite beautifully) that he was a proud Canadian who never became a US citizen, and thus deserved a vote.

One problem: this proud Canadian hasn’t lived in Canada since the late 1960s. That’s 11 Prime Ministers ago.

Sutherland, for what it’s worth, says he would vote NDP – and that’s fine. Thousands of resident Canadians feel the same way. But just as a thought exercise, consider what that means. It’s not a stretch to suggest that a Jagmeet Singh-led government, for example, would at least consider raising income taxes.

Sutherland would, in effect, be voting for higher taxes that he will never have to pay.

So, again: aside from a local candidate representing a place he doesn't live in, and a general endorsement of a party's broader vision - what would he be voting for?

It's easy to vote for somebody else's taxes to go up; quite another to pay them yourself.

I’m not picking on the NDP, or even higher taxes – Sutherland said that’s his voting preference. It works for any expat and any party.

Imagine (and this is completely hypothetical) that former B.C. resident Chad Kroeger is a fervent Conservative. Why should that vote count towards electing a representative – and Conservative policies – in Vancouver? He doesn’t live there anymore.

What about a Canadian who happens to play for the Vancouver Canucks before being moved to a U.S. franchise? Should he have a legacy vote in Yaletown?

There's a slippery slope underfoot. Yes, the Supreme Court ruling only applies to federal elections – but why should or would it stop there? If voting rights are absolute, there's no immediately apparent reason it shouldn't apply to interprovincial expats.

To use myself as an example, I grew up and later worked in Calgary, but also spent several years in Ottawa, and still (mostly) have the addresses and reasonable documentation. I was registered with both Elections Alberta and Elections Ontario. Should I be entitled to a vote in those provincial and even municipal elections?

Again, if your answer is yes – why?

Yes, it could be worse. I worried the Court – and Cabinet – might have decided to let expats pick and choose their ridings, which would have opened the doors to coordinated efforts targeting swing riding(s). And we’re not talking about Canadians who maintain homes here whose work, studies - or seasonal weather - takes them elsewhere.

But at the risk of being on the unfashionable side of this debate, it’s difficult to see why people who have chosen to permanently live (and pay taxes) in another country since before I was born suddenly need to have their views reflected in our elections.

Maclean Kay is Editor-in-Chief of The Orca