B.C.’s beleaguered small business grant program received its third overhaul this past week, and the question was not whether the reforms were needed but rather: What the heck took so long?

Economic Recovery Minister Ravi Kahlon extended the program’s deadline Thursday to avoid almost $250 million in unspent grants – out of a program budget of $300 million – disappearing on March 31.

A new Aug. 31 deadline wasn’t the only reform. Kahlon relaxed criteria, so that businesses no longer have to lose 70 per cent of their revenue to be eligible, and can instead qualify at 30 per cent.

“We are committed to making sure hard-hit businesses can access these critical funds,” Kahlon said in a release.

As I’ve stated before, Kahlon is one of the NDP’s superstar young ministers, with mastery of his file and excellent communications chops. So it was surprising to watch him take so long to enact obviously-needed reforms.

All the delay did was open Kahlon up to easy attacks by the Opposition BC Liberals in the first week of the session.

Change was inevitable. A program that has failed to spend 83 per cent of its budget after almost six months, while businesses are begging for financial help, clearly needed to be sent back for a redraft.

For what went wrong with the small business grant program, we can begin to search for clues in other similar COVID-19 relief measures.

The most relevant is the B.C. Recovery Benefit, a payment of up to $1,000 for families, based on their income, which went live around Christmas.

The recovery benefit arrived later than Premier John Horgan promised, in a form that relied on people’s 2019 tax returns for eligibility and therefore failed to help those who had actually lost work due to the pandemic.

Hundreds of thousands of people struggled to navigate the application process, finding themselves subject to a bogged-down “review” process that took months.

The core problems boiled down to how the civil service designs programs, and how its overarching considerations are to avoid fraud and properly manage risk, Finance Minister Selina Robinson told the legislature in December.

“The other thing is that when we have this kind of program, it has to undergo the financial risk and controls review at the office of the OCG (Office of the Comptroller General) to make sure that we are managing the risks to the significant funds that are going to be delivered to British Columbians,” she said at the time.

That’s why the government settled on the previous year’s tax returns - even though it meant not delivering on its promise to help those who had actually lost their jobs. And that’s why the program was late - even though the premier had promised the money would flow before Christmas.

“This was the best outcome and the best tool, framework, that we could put together that would deliver to the people that need it most, do it in a timely way and also have the risks mitigated when you have such a significant undertaking,” said Robinson.

To be clear, that’s a healthy sign our system of government is working.

On the one hand, you have politicians promising the moon.

On the other, you have non-partisan civil servants translating those promises into programs that work in the overall best interest of taxpayers, with the maximum respect for their money, in the fairest way possible.

It’s a perpetual balancing act.

Politicians have an important role here too, because they infuse public pressure and real-world dynamics into what can be a slow-moving, unaccountable and at times out-of-touch civil service. Left unchecked, the bureaucracy would design programs so slowly, with so many rules and criteria, as to be unusable.

I suspect it is here that we encounter the problems that pervade the small business grant program. There’s too much paperwork. Too many hurdles to jump through. The eligibility criteria was far too high. The requirement for a “COVID-19 recovery plan” by each business - to prove they had a viable business model in the pandemic and weren’t destined to fail - was too onerous.

It added up to far too much red tape.

Kahlon recognized this in December and authorized up to $2,000 per business to help hire professional accountants and financial advisors to navigate the application process and craft the recovery plans.

It was a good idea – but also a clear warning sign this program was deeply flawed.

With this third refresh, is the small business program going to actually start handing out significant money to the businesses that need it? Well, the third time’s a charm. We’ll see in August if it actually worked.

Rob Shaw has spent more than 13 years covering BC politics, now reporting for CHEK News and writing for The Orca. He is the co-author of the national best-selling book A Matter of Confidence, and a regular guest on CBC Radio.

SWIM ON:

- Rob Shaw last wrote about the continuing saga of the NDP government's attempt to overhaul auto insurance - and the long shadow cast by the latest court setback.

- In June, Jock Finlayson delved into what can only be called business destruction.

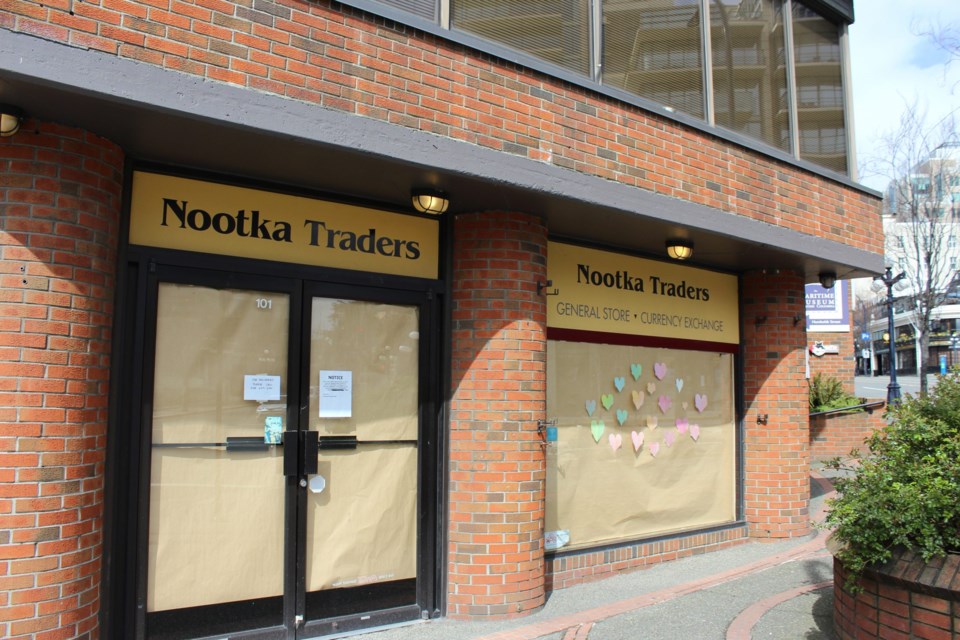

- In search of new ways to appeal for a shrinking pot of disposable income, COVID-19 forced small business owners to show their human side, says Ada Slivinski.