As Finance Minister Carole James said, “electoral reform is finished.”

For British Columbians who voted, campaigned and hoped for some form of proportional representation, it doesn’t seem likely the issue will be revisited anytime soon – you usually only get three strikes.

After a campaign supported by two of B.C.’s three major parties (plus both the BC Conservatives and the Communist Party of Canada), where the bar for success was lowered to the point of straining credibility – it’s only fair to ask why they not only lost, but so decisively.

Confusion

Premier John Horgan promised a Citizen’s Assembly, a single option, and a simple yes/no question – each of which probably would have given the process more credibility and simplicity. But for whatever internal reasons – which I’m sure we’ll learn in due course – that’s not what happened.

Of those who did support Proportional Representation, Mixed-Member turned out to be a prohibitive favourite – that should be no surprise, because it’s actually used elsewhere. Attorney General David Eby’s decision, backed by Horgan, to include two ill-defined and experimental systems only served to muddy the waters.

System Failure

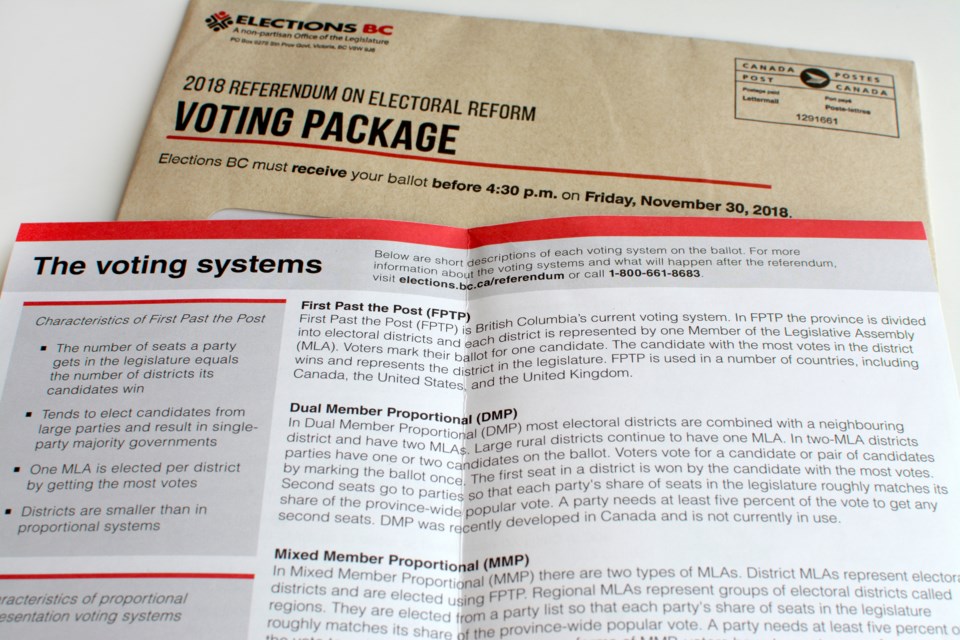

Key details of each proposed PR system were left to be decided after the fact – even entry-level fundamentals like “how many votes do I get” and “how many MLAs will I have.” These were entirely fair concerns, hand-waved away as fearmongering.

Also, giving this file to Eby was probably a mistake. Smart, dedicated, and hardworking – not for nothing did he unseat Christy Clark – Eby had two problems. First, his ministry was busy, even by the ambitious standards of this government, and this file probably endured stretches at the back of the pile. Eby is also strikingly partisan, even among partisans; he was never going to be accepted as a neutral arbiter.

This could have been tacked onto literally any other ministry; if the previous government could create a ministry of Natural Gas and Housing, there’s no reason the NDP couldn’t have Minister of X and Minister Responsible for Electoral Reform.

Partisan Exercise

Green leader Andrew Weaver was clear: he believed PR would mean no more BC Liberal majority governments – and he wasn’t alone, both in his party and the NDP.

Making this into a straightforward NDP/Green vs. BC Liberal handicap match not only wrote off the support base of the province’s largest party, but mobilized and motivated them – which the results made abundantly clear.

It also likely alienated a significant core of voters who don’t identify with any particular party, but were turned off by a governing party openly trying to create a system that would benefit them and hurt their opponents. In any other context, we’d call that gerrymandering.

As a result, the Yes side had to fight on two fronts: build a case to change our electoral system, and defend a rushed, partisan process. Once again – an entirely self-inflicted wound.

A unicorn in every pot

PR had one big advantage over First Past the Post: arguing for hope, change, and “fairness,” against a system whose warts and flaws are well known. Aspirational campaigns are often successful in B.C. – but those aspirations must seem realistic.

Almost from day one, too many claims for PR were not even compellingly plausible, much less realistic.

The Sierra Club said salmon need PR. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives added “countries using PR were more ready to pay the price of strong environmental policies,” a bit of wild extrapolation that was supposed to sound enticing. Fair Vote Canada, presumably with a straight face, claimed it would reduce domestic terrorism.

Even some of the more thoughtful arguments fell back on articles of faith – it would be better for women/voter turnout/general fairness/etc. because, well, it just would be. Stop fearmongering.

Some voters tuned out, and some resented having their intelligence insulted.

The world is not enough

Real world events – and difficulties in countries using PR – intruded at the worst possible times. There were a few examples, but the most damning was Sweden’s September election, which vaulted the far right into a role of real influence.

Too often, even bringing up these real-world examples was dismissed as “fearmongering.” But one of the main selling points for PR was that small and single-issue parties have an easier path to legitimacy.

Fumbles

The Yes side endured a handful – not a lot, but some – of damaging missteps and mistakes.

Perhaps most notably, Melanie Mark was embarrassed by a camera crew she had invited to come doorknocking with her, saying “she wasn’t an expert” in PR – which didn’t help the narrative that PR was simply too confusing.

In the leader’s debate with Premier John Horgan and BC Liberal leader Andrew Wilkinson, Horgan was unable to answer questions about details – because nobody knew them, and that was the point. This should have been anticipated as a vulnerability, but Horgan seemed to be caught off guard.

The No side didn’t have a perfect campaign, with a few unfortunate Internet memes which may well have alienated some voters. But they amounted to stumbles; the Yes side scored some own goals.

Not all correlations are created equal

Voters can (and did) support parties that support some form of electoral reform – but barring a single-issue election, it’s risky at best to infer that’s why they chose that party.

As CFAX’s Adam Stirling pointed out, of the three referenda, 2018 had the lowest proportion of registered voters supporting PR – just 16.38%.

These results indicate precious few British Columbians feel particularly passionate about PR.

Turnout, turnout, turnout

The Yes side needed the Lower Mainland to turn out in droves; that simply didn’t happen. By contrast, not only did rural BC turn out, they overwhelmingly voted to keep the current system.

For example, PR’s strongest riding was NDP stronghold Vancouver-Mount Pleasant, with more than 74% voting for PR. Sounds impressive as a percentage, but in terms of raw numbers – which is what counted – the riding still delivered fewer Yes votes than (for example) much-smaller Vernon-Monashee did for the No side.

There’s really no sugar-coating things: it’s a big defeat for the NDP. There are arguments this is a bigger blow to the Greens, and perhaps in terms of a lost electoral opportunity, that might be true.

But the NDP set the terms of this referendum, and are now faced with the worst possible outcome: the perception that they tried to rig it, and failed.

Maclean Kay is Editor in Chief of The Orca