The tragic overdose deaths of two teenagers on Vancouver Island has exposed the gaping holes that still exist in B.C.’s mental health and addictions system, as well as the appalling rhetoric and politicking that continues to undermine our province’s response to its most vulnerable.

Allayah Thomas, a 12-year-old Grade 6 student, died of a suspected overdose in a friend’s Langford home late last month. She’d overdosed three prior times, but in each case refused help and was discharged from hospital.

Bella Jones, a 17-year-old Nanaimo girl, also died of a suspected drug overdose last week. She’d been struggling with addictions since she was 13, and her mother had signed custody of her over to the Ministry of Children and Family Development in a last-ditch attempt to get her help.

In both cases, the families had appealed to the government for help, but didn’t get it before their daughters fell victim to the toxic drug supply that has fuelled the overdose crisis.

The deaths of the two teens just so happened to fall in the ridings of the two politicians who could actually change the system for the better: Juan de Fuca’s Premier John Horgan and Nanaimo’s Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson.

Yet they were nowhere to be found in the days following CHEK News reporter April Lawrence breaking these stories and airing the pleas of family and friends for more help.

Both cited the “privacy restrictions” of the deceased teens for their inability to say anything about how the system could be improved to fix the gaps identified by these deaths.

“Because of privacy laws, we are unable to comment further at this time,” said Malcolmson’s ministry.

“Due to privacy laws and out of respect for the family, the premier is unable to comment,” said Horgan’s office.

That held for almost an entire week, before Malcolmson appeared at a press conference touting her ministry’s accomplishments on youth mental health and addictions, where she was hit with questions about Thomas’s death.

“That there was someone as young as age 12 is shocking and again this is a terrible story that just restrengthens our commitment as a government to build the kind of addictions and mental health care system that anybody can access,” said Malcolmson.

But can her ministry, or the Ministry of Children and Family Development, explain how these kids were failed by our system, and what lessons if any we’ve learned to try and prevent future deaths?

No, because of privacy concerns.

The privacy stonewall is one used by governments of all stripes for more than a decade now. The previous BC Liberal government hid behind it for years during a child death crisis in the mid-2010s, in which high-profile cases of suicides and overdoses by kids in ministry care were routinely highlighted by the independent Representative for Children and Youth.

The cases were appalling: a legally blind girl who fell through all the cracks in the system before overdosing alone in a filthy washroom in Vancouver’s Oppenheimer Park; a teenaged boy who was placed by his social worker in a hotel in violation of government policy before jumping out a window to his death; a 19-year-old girl who was neglected and abused within the system and who jumped off the Lions Gate Bridge only 20 hours after she officially aged out of government care.

The BC Liberals argued for years they couldn’t talk about these cases due to “privacy” - not through media requests, to the families, or in the form of questions in the legislature.

That excuse reached the peak of absurdity in 2015, when government lawyers sent the parents of Nick Lang, a 15-year-old who had died in a provincially-run addictions treatment facility in Campbell River, a letter instructing them to stop speaking publicly about their son’s death because it was posthumously violating his privacy rights.

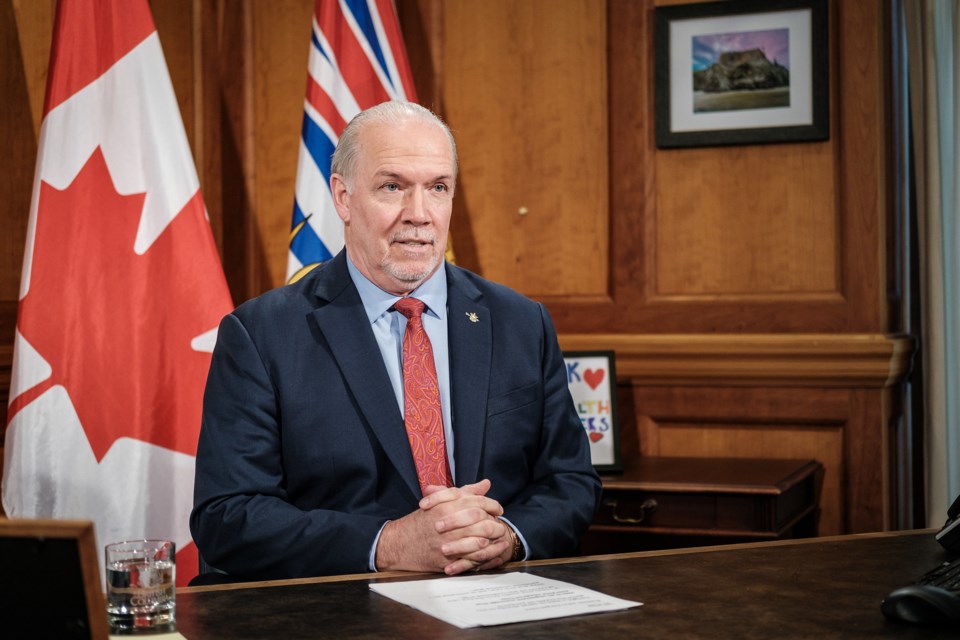

Then Premier Christy Clark had to stand up and apologize for the letter in the house. Across her was the hulking, fuming, outraged form of Horgan, then leader of the Opposition, who railed on government for weeks about its callousness, and the cowardly nature of using the privacy of the dead as a political shield.

"A lawyer wrote to the family and said they were violating the privacy of their dead son - if that's not the most heartless thing you've ever heard I don’t know what is,” Horgan told the legislature in 2015.

He shredded the government - quite rightly - for several years on its failures to protect vulnerable children. He called on Clark to show some leadership. At times he was so mad you could see him shaking in the house.

“The decisions made by the premier are directly affecting the lives of children in B.C.,” he said.

“Wake up, premier. Do something about it."

Fast forward six years.

Horgan is premier.

Children are still dying.

And now his government is deploying the excuse of “privacy” to avoid responding to questions about how the system failed and can be improved.

There’s an old adage in B.C. politics that if you stick around long enough you end up becoming everything you ever hated about your opponents.

It’s hard not to think about that when you watch the New Democrats lurch through this crisis, deploying the same bag of tricks and excuses to avoid basic accountability.

It was wrong when the B.C. Liberals did it. It remains wrong when the New Democrats do it. And will still be a pathetic excuse whenever the next government tries it too.

Rob Shaw has spent more than 13 years covering BC politics, now reporting for CHEK News and writing for The Orca. He is the co-author of the national best-selling book A Matter of Confidence, and a regular guest on CBC Radio.

SWIM ON:

- Rob Shaw last looked at the revelation that heath authorities have been withholding pandemic data, and wonders what they were thinking.

- Justin P. Goodrich welcomed Jeff Hardy and Madeleine Hardin of LifeGuard Digital Health to look back on five (official) years of the opioid crisis.

- Sylvain Charlebois: Prices will go up by as much as five per cent this year, or almost $700 more for groceries for the year for an average Canadian family.