A few months ago, I went to visit a friend who lives out past Sooke, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, who had made a most mysterious archeological find.

Traveling into Sooke one day (named after the T'Souk-e people), he parked his car outside an office, opened his car door, and immediately heard an object hit the ground from the sky. Stepping out of the vehicle, he cast his eyes about to discover that a seagull had dropped something from the air – and was now about to retrieve it.

At first, my friend thought it a piece of plastic, and thought it best to liberate the object; perhaps the bird thought it a nut to be cracked, or a shellfish to be opened? To my friend’s surprise, it turned out to be some sort of arrowhead.

He asked whether I could assist in identifying it. I took a few snaps on my phone, and borrowed it to conduct further investigations.

“This is astounding,” I remarked while taking the above picture. The colour of the stone was unlike any I had seen before, and well knew that such Indigenous antiquities along the southeast coast of Vancouver Island could approach the elusive age of between 8,000 to 11,000 years old. But the red colour made this find strikingly different, if not an anomaly, compared to other artifacts seen over the years.

I subsequently posted pictures for friends in the various history communities I am associated with throughout BC and the larger Pacific Slope region.

The response was fantastic.

Hundreds of opinions were offered. “It’s an arrowhead,” most claimed. “No, it is a knife, or possibly a scraper” others suggested. Throughout the dialogue, most of these history enthusiasts asked that I keep them posted if further information was forthcoming.

The public demanded to know! This spurred further investigation a few weeks ago, and here are the results of my detective work.

Who better to contact than my old friend Grant Keddie, the Curator of Archaeology at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM).

Keddie, in many ways the keeper of provincial antiquities, is about to be recognized this fall for 50 years of exemplary service to this province – an incredible achievement – and Grant has always been so good about taking time from his immensely busy schedule to assist in identification of the myriad of artifacts uncovered in BC.

“So, what have you got for me today?” enthused Keddie.

I presented him with the sky-born artifact. After an initial examination he promptly said, “I guess you found this in the Interior of the province?”

I smiled in return (having yet to tell him it had been dropped by a seagull), “No, actually it was found in Sooke!”

With that, we took the elevator to his office in the RBCM’s large Curatorial Tower that house the museum’s immense collections not ordinarily on display.

I asked him from what kind of stone the artifact had been made from? “Red Chert” was the instantaneous answer, with no equivocation from a curator with vast experience in these matters. I knew that obsidian arrowheads had been found on Vancouver Island traceable to lava flows in Terrace or as far away as Oregon. But is there an identified source for Red Chert in the province?

The answer – there is no known source in BC. It definitely came from south of the border.

“There are many artifacts made from this material found in the mid-Columbia River region,” said Grant, “but even in that location, the source is still not known.”

Keddie next consulted his old card catalogues, as I had asked him whether other Red Chert artifacts had been discovered in southern Vancouver Island.

“Not too many at all really, and certainly not as large as the one you have brought in today,” further suggesting only a very few had been collected in the Saanich and Sooke regions.

With each of Grant’s revelations, my curiosity was continuing to grow:

“Can we possibly look at those examples that have been found close to Sooke?”

The renowned archaeologist proceeded to the back room, overflowing with hundreds of cabinets filled with ancient curiosities. In short order, Keddie opened the Pedder Bay drawer – the closest collection of pertinence.

Grant plucked out two objects manufactured from Red Chert collected at this site and placed them on a research table. I slid the seagull-dropped object next to them for comparison.

Again, he reiterated that the few instances of Red Chert-made implements discovered on the Island were rather small next to the one my friend had liberated from the seagull in Sooke.

“If I were a betting man, I’d say that your friend’s artifact dates between 2,000 to 4,000 years old, and perhaps much more,” said Keddie, also concluding it was once twice the size and therefore possibly an arrowhead – but more likely an impressive stone knife.

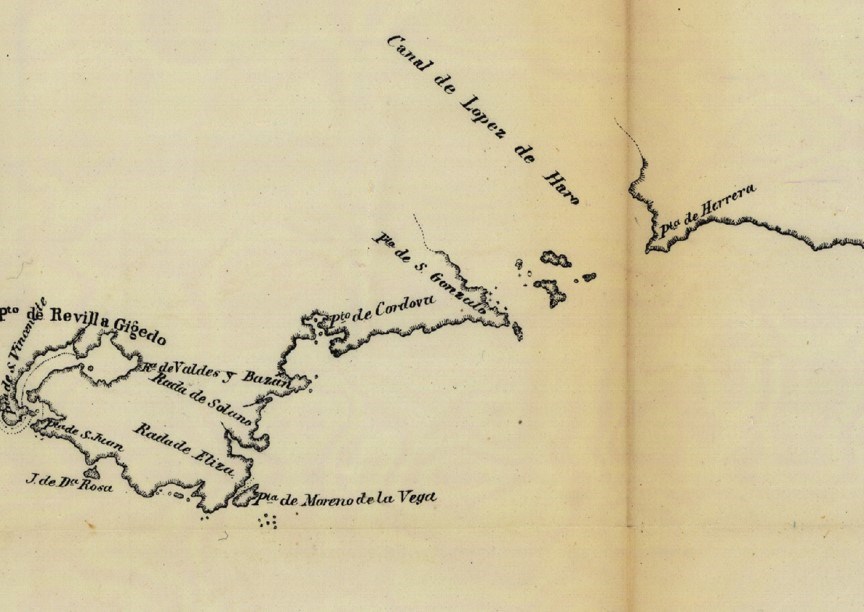

Keddie confirmed that Indigenous archaeological sites existed throughout Sooke Harbour (no surprise really) and that Spanish explorations had recorded a Native village right below the town of Sooke. The Spanish, of course, had claimed possession of Sooke Harbour or “Puerto de Revillagigedo,” named for the viceroy of New Spain (Mexico). This was the first recorded European exploration of the Quimper/Eliza voyages that stayed in this locale in the year 1790, just one year after the Nootka Crisis between Spain and Britain at Yuquot (“Friendly Cove” as Captain Cook called it) on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

This was all very fascinating, of course, but I still wanted to know: how did this extraordinary stone knife make it to Sooke?

Keddie suggested two possibilities: either it was carried during Native warfare from out of the depths of the Puget Sound region; or more likely, through the extensive Indigenous trade networks that once flourished throughout the Pacific Slope region.

The many more examples of Red Chert artifacts in the Okanagan and Kootenay regions certainly suggests the possibility that it may have been traded or carried north from below the current international border, from the Mid-Columbia (and perhaps even further south) into the lands of the Interior Salish. From there, it may have been subsequently traded down the Thompson and Fraser River corridors, and then to the Island.

Indigenous nations on the coast are known to have traded large quantities of dried clams as far away as Spokane in eastern Washington, and the coastal dentalia shell has been found as far east as the Mississippi River. By the time of the land-based fur trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company was well aware of these extensive trade networks. My good friend and colleague HBC Historian Richard Mackie has stated that the HBC simply grafted company operations onto these pre-existing Indigenous trade networks.

So, there you have it. But the question remains – just where did the seagull get it, and since when do seagulls loot archaeology sites?

The bird obviously failed to crack the “clam” – but I hope I can say I cracked the case of the anomalous antiquity that fell from the sky.

Thank you Grant Keddie, deeply appreciated.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.