I remember taking my grandfather for a drive around Victoria, traveling the countryside of his youth, and reliving stories of the past about Old Victoria.

There was nowhere that we passed by that did not spark memories.

Winding our way down Quadra Street we paused at Saanich Road, Gramps happily puffed away on his Meerschaum pipe as he excitedly remembered the site of Victoria’s last remaining wolf den at the intersection of these two roads, the original family home not far away, and still standing.

Towards the funky old community of Fernwood, the pipe stoked once more, he would say things like, “Oh, that’s where Dad and Uncle Nick used to hunt pheasants!”

By the time we reached the Inner Harbour these stories only continued to grow. He noted that his father was accustomed to hunt ducks in what was James Bay before it was filled in to make way for the Empress Hotel.

Of course, he marveled at the extent of business and residential development that had sprawled over the once pristine countryside. Occasionally he would grumble, too, that things had gone downhill once all the eastern Canadians had moved in after the First World War – usually mentioned in the presence of my Ontario-born grandmother!

It reminded me of similar road trips with Indigenous elders throughout their traditional territories. For them, seeing the landscape firsthand was usually the trigger for remembering stories of the past, especially amongst oral cultures who see the land as a history book.

This was also very much the case for my grandfather.

Born in 1904 on the family farm at Christmas Hill situated above Swan Lake in what would become Saanich, a location first homesteaded by my great-great-great Uncle William in 1860, just two years after having joined the Fraser River gold rush of 1858.

As the day rolled on, and with the assistance of additional tobacco, the stories only increased. He shared a great journey he and his father made when just nine years old.

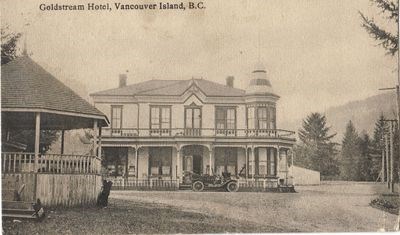

His father, a die-hard member of the Conservative Party, was up early one morning on the farm, busy saddling up one of their horses to a democrat (or buggy) to make the long journey from Swan Lake to the Goldstream Hotel, nearby today's Ma Miller’s Pub adjacent to Goldstream Provincial Park.

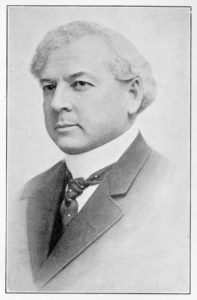

The old man was in a hurry – “tiredness is laziness” – as he announced they would travel to see Premier Richard McBride give a speech in what the British Colonist of July 27, 1913 called “the sixth grand Conservative picnic.”

While other members of the public chose to take the E & N Railway to the “red letter day,” he chose the more old-fashioned method of travel. He had apparently become Saanich’s superintendent of roads, so perhaps he was also inspecting the early “highways.”

After a long horse-drawn ride, they and hundreds of other picnickers watched fiery speeches from well-known politicians, but “unquestionably, the piece de resistance was the speech made by Sir Richard McBride” enthused the British Colonist.

Throughout my grandfather’s life, when referring to McBride – a most popular politician of the times – he was always referred to rather affectionately as “Dickey.”

Such was “Dickey’s” popularity that years later Dr. Margaret Ormsby (the first woman to hold a permanent position in a Canadian history department) devoted an entire chapter of her book, British Columbia: A History, entitled, rather innocently, “The People’s Dick.”

After publication, Ormsby’s UBC colleagues took the professor aside and suggested, in hushed tones, that she might want to rethink her chapter title.

BC book collectors and bibliophiles would do well to remember that subsequent editions renamed the McBride chapter “The People’s Choice.” And now you know the key for identifying first editions.

I was fortunate to have many such expeditions with my grandfather before his death in 1997, and it was during these times that I learned the most.

In the natural landscape of the Indigenous world, the mountains, rock spires and boulder-strewn streams record the memories of the ancient past, history embedded into the very geography. From the Indigenous perspective, long before history books were ever created, the natural world was like a book itself, to be read and reread by each successive generation.

In oral cultures, one could walk the landscape and literally watch history unfold before his or her very eyes. And so, in a similar way, my grandfather – my own elder – traveled the landscape that day and shared the oral history of our family that has spanned the generations from the Colony of Vancouver Island, then the “United” Colony of British Columbia, and finally as a province of Canada.

And when I next happen by Ma Miller’s Pub for a quick pint, I will be thinking of my grandfather, his hundreds of stories, and raising a glass to his memory. Many thanks Gramps, you were my living link to British Columbia’s historic past.

Cheers!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.