It’s easy to take for granted today, but the “British” part of British Columbia’s history was never a foregone conclusion.

Spain, the United States, and even Russia had equally viable claims – and were it not for a remarkable Indigenous leader and the way he dealt with the first European and Americans to his shores, history may well have unfolded differently.

For centuries, Spain treated the Pacific Ocean as a Spanish lake. Only the occasional British freebooter – such as Sir Francis Drake – challenged their otherwise unrivaled supremacy.

In 1778, this changed with the arrival of Captain James Cook in Nootka Sound, launching the maritime fur trade and the great rush for sea otter pelts to what was considered, from a European perspective, the last unmapped coastline in the world.

Landing at Nootka, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Cook recorded one of the earliest European views of Indigenous conceptions of property rights. Cook instructed his crew to obtain a variety of resources, and quickly found that the Mowachaht people demanded fair payment. With respect to cutting grass, in particular, Cook stated:

“I had not the least imagination that the natives could make any objections to our furnishing ourselves with what seemed to be of no use to them, but was necessary for us. However, I was mistaken; for the moment our men began to cut, some of the inhabitants interposed and would not permit them to proceed, saying they must makook; that is, must first buy it.”

Captain Cook’s observation is important. He had entered an Indigenous world that had yet to experience, or be altered by, the intense trading practices of the maritime fur trade that shortly ensued. Cook continued:

“Here I must observe that I have nowhere, in my several voyages, met with any uncivilized nation, or tribe, who had such strict notions of their having a right to the exclusive property of everything that their country produces, as the inhabitants of this Sound.

At first, they wanted our people to pay for the wood and water that they carried on board; and had I been upon the spot, when these demands were made, I should certainly have complied with them. Our workmen, in my absence, thought differently; for they took but little notice of such claims and the natives, when they found that we were determined to pay nothing, at last ceased to apply. But they made a merit of necessity; and frequently afterward took occasion to remind us that they had given us wood and water out of friendship.”

Though Cook’s instructions were “with the consent of the natives, to take possession in the name of the King of Great Britain of convenient situations in such countries as you may discover,” he nevertheless made no attempt to formally claim sovereignty at Yuquot (‘Friendly Cove’). In fact, he concluded that the Mowachaht “considered the place as entirely their property, without fearing any superiority.”

In short order, the maritime fur trade commenced, primarily by British and American commercial enterprises.

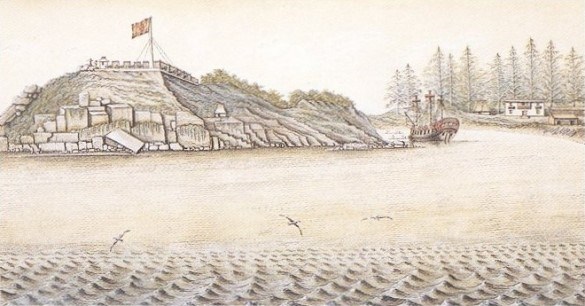

Spain quickly reacted. The Spanish fort of San Miguel was immediately established, then abandoned – but not before two British ships were confiscated and their captain, James Colnett, incarcerated in San Blas, Mexico.

This led the British government to demand restitution and press a competing claim of sovereignty.

Restitution would also demand recognition of land purchased at Yuquot for establishment of a fort by John Meares, apparently conveyed by Chief Maquinna – though he later denied it. The “Nootka Crisis” of 1789 coincided with the fall of the Bastille in revolutionary France; without its old ally, Britain realized Spain was substantially weakened – and seized the moment.

Britain asserted that Spain’s claim of prior rights of discovery were insufficient for exclusive ownership, and instead argued (with the threat of military force) that rights of discovery could only be maintained through continuous occupation.

Spain acceded. This proved to be a decisive turning point; not only in the decline of the Spanish Empire, but ultimately made it possible for Canada to extend its sovereignty to the Pacific, some 80 years later.

The story doesn’t end there. Mostly forgotten today, there were other competing non-Indigenous sovereignties on the Northwest Coast during the “Nootka Crisis.”

In 1791, Chief Maquinna and five sub-altern chiefs sold land in Nootka Sound to John Kendrick, an American captain. Ten muskets were apparently traded for the purchase and the chiefs put their “X’s” to a formal deed of sale.

Like the Meares claim, Kendrick’s was viewed as a possible basis for American sovereignty in the region – particularly by President Thomas Jefferson. The text of the Kendrick Treaty reads:

To all persons to whom these presents shall come: I, Macquinnah, the chief, and with my other chiefs, do send greeting:

Know ye that I, Macquinnah, of Nootka sound, on the north-west coast of America, for and in consideration of ten muskets, do grant and sell unto John Kendrick, of Boston, commonwealth of Massachusetts, in North America, a certain harbor in said Nootka sound, called Chastacktoos, in which the brigantine Lady Washington lay at anchor on the twentieth day of July, 1791, with all the land, rivers, creeks, harbors, islands, &c, within nine miles north, east, west and south of said harbor, with all the produce of both sea and land appertaining thereto; only the said John Kendrick does grant and allow the said Maquinnah to live and fish on the said territory as usual.

And by these presents does grant and sell to the said John Kendrick, his heirs, executors and administrators, all the above mentioned territory, known by the Indian name Chastacktoos, but now by the name of the Safe Retreat harbor; and also do grant and sell to the said John Kendrick, his heirs, executors and administrators, a free passage through all the rivers and passages, with all the outlets which lead to and from the said Nootka sound, of which, by the signing these presents, I have delivered unto the said John Kendrick.

Signed with my own hand and the other chiefs’, and bearing even date, to have and to hold the said premises, &c., to him, the said John Kendrick, his heirs, executors, and administrators, from henceforth and forever, as his property absolutely, without any other consideration whatever.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and the hands of my other chiefs, this twentieth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-one.

Largely forgotten to history, the Kendrick Treaties are extraordinary for their time. The land purchase was confirmed the following year by both the Spanish and British authorities through interviews with Chief Maquinna himself. As the historian Warren Cook has stated:

A year later the Spanish would endeavor to secure a deed of purchase from Ma-Kwee-na. Loyal to his agreement with Kendrick, in the new sale the old chief expressly exempted the land conveyed to his American friend. Although not then at Nootka, Kendrick heard about this; conceiving that his deeds possessed diplomatic importance, he registered them with the American consul in Canton and remitted duplicates to the American government.

The American claim to what is today British Columbia was substantial, especially having subsequently inherited Spain’s prior rights of discovery to the Northwest Coast. It wasn’t until the Oregon Boundary Settlement of 1846 (which extended the 49th parallel to the Pacific) could Britain claim “undivided sovereignty” of what is today Canadian territory.

That’s why 1846 is considered the critical year for confirming pre-existing indigenous sovereignties within British Columbian and Canadian courts today. By then, land transactions between Indigenous peoples and colonial authorities were based on this principle: continuous use and occupation determined rights and title.

For First Nations in coastal British Columbia, the historic record of the maritime fur trade provides substantial evidence of continuous use and occupation of traditional territories prior to 1846 – the kind of evidence demanded by courts.

For inland Indigenous Nations, the written historic record prior to 1846 may be slim at best, and thus difficult to provide ‘proof’ according to the, at times, seemingly self-justifying European rules of the game.

The Nootka Crisis not only defined how rights and title would be defined in British Columbia, but set a different course for B.C. which could otherwise just as easily ended up part of Mexico, the United States, or possibly even Russia.

That, also, is something to reflect upon these days.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.