In a world that seems increasingly divided by ethnic and racial tension, it’s worth remembering those who sought asylum here more than 160 years ago.

Imagine you were a Black American parent living in California. Your young daughter was assaulted by a white American. You have no legal recourse; black testimony has become inadmissible in courts of law.

Imagine how you’d feel as a high-ranking Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) official, partnered with an Indigenous woman, having your mixed-race children disenfranchised – their rights stripped – in their own home territory of Southern “Old Oregon” (Washington, Oregon and Idaho).

These grim imaginings actually happened – yet remain largely forgotten.

Before the international border was established, there was a period of joint British-American sovereignty on the Northwest Coast.

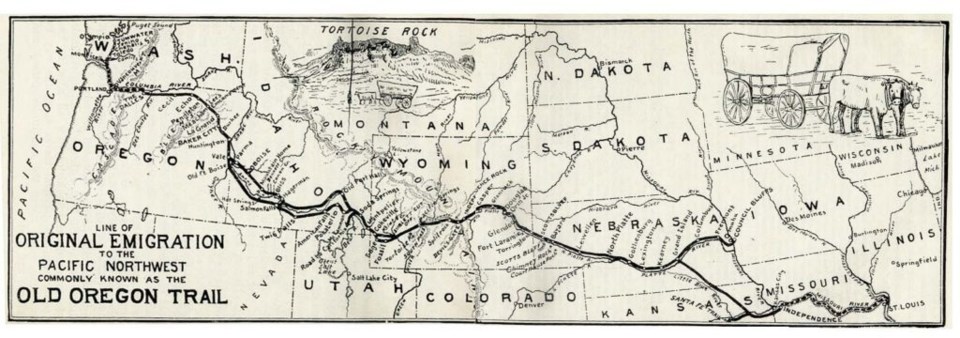

This is where – and when – ‘Old Oregon’ was born; when American pioneers went west over the Oregon Trail to claim lands already occupied by the HBC, let alone the Indigenous peoples of many nations and languages who had lived on these lands since time immemorial.

James Douglas, the future governor of British Columbia, was himself of mixed race, Scotch-West Indian ancestry and had experienced, firsthand, the increasingly exclusionary policies adopted in Old Oregon, particularly after 1843.

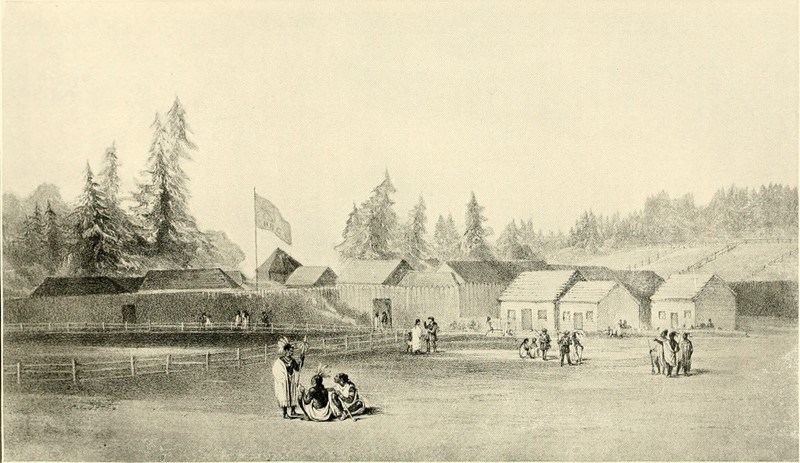

That same year, a substantial increase of American settlers forced the HBC to relocate its headquarters from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River to Fort Victoria.

As US historian John Jackson has noted, most of these early American pioneers “came from communities that feared and firmly repudiated racial intermarriage, believing it a threat to frontier survival.” In 1845, they seized political control of Oregon’s provisional legislature, and made laws for their own benefit.

Douglas’ predecessor, Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin (the “Father of Oregon”), wrote of the changing circumstances brought by these American squatters imbued with notions of Manifest Destiny:

It is reported that some of the immigrants last come have said that every man who has an Indian wife ought to be driven out of the country, and that the half-breeds should not be allowed to hold lands.

Policies of exclusion soon unfolded, Oregon’s infamous “Lash Law” of 1844, though lasting less than a year, directed that blacks, whether slave or free, be whipped twice a year “until he or she shall quit the territory.”

By 1862, Oregon had adopted a law that required all Blacks, Chinese, Hawaiians, and “mix-bloods” residing in the state to pay an annual tax of $5. Black/white intermarriage was banned, and this prohibition was subsequently extended in 1866 to anyone who was ¼ or more Chinese or Hawaiian, and ½ or more Indigenous.

Oregon became the model for California. Writing in the early 1860s, the historian John Hittell recorded similar exclusionary laws of the Golden State under the title of the “Inferiority of Colored Persons”:

All white male citizens are equal before the law of California; but negroes, Indians and Chinamen are not permitted to vote or to testify in the courts against white men. In a criminal case, one-eighth negro blood and one-half of Indian blood, in civil cases one-half of either, disqualifies a witness for testifying against a white man.

Contrast this with British Columbia, which embraced, and then advanced, the principle of equality under the law – for all.

By these provisions, if Governor Douglas had been implicated in a Californian criminal proceeding, he would have been precluded from giving evidence. His wife Amelia (whose mother, Miyo Nipiy, was of the Cree Nation), would also have faced such discrimination.

That much is still fairly well known. But mostly untold is that practically all HBC families, after an extended period of partnership with Indigenous allies – a partnership that had built a shared and longstanding commerce – were now essentially pushed out to the British side of the new border.

The circumscribed fur trade society north of the 49th parallel continued its unique relationship between British traders and Indigenous allies and partners. But the ethnic and racial diversity was actually more complex.

First, from a British perspective, there were the English, but also the Celtic peoples of the Scottish, Irish, Cornish, Welsh, and Manx among others. So, too, there were the many native nations here along the coast, such as the Lekwammen, Quw’utsun, Nuu-chah-nulth, or Kwakwaka’wakw to name but a few (not to mention the Interior B.C. peoples such as the, Secwepemc, St’at’imc or Nlakapa’mux).

Add to this mix the French Canadiens and Metis, along with the Cree, Mohawk, Ojibwa, and Iroquois, who came along with the fur trade. Finally, significant numbers of Hawaiians employed in the fur trade, and Mexican peoples originally employed as muleteers for the HBC.

Clearly, the fur trade was synonymous with racial and ethnic diversity.

So while the American historian Susan Johnson notes the gold rushes were “among the most multiracial, multiethnic, multinational events that had yet occurred within the boundaries of the United States,” the lands known as “Old Oregon” (prior to the 1846 partition) had already experienced a much longer period of such diversity – but in a significantly much more inclusive way.

North of the border, this shared world continued after 1846, immeasurably enlarged with the addition of gold seekers – who in many instances were also seeking asylum from persecution.

Many of these asylum seekers went on to make great contributions to British Columbia, including Victoria’s first black city councillor.

This is important context. It provides one of the key reasons British Columbia’s gold rush experience unfolded much differently, in a comparatively much more inclusive way.

Without these early polices of inclusion, it’s doubtful whether the mixed-race B.C. politician Simon Fraser Tolmie – whose mother was part Spokane native – could have become Premier.

Today, it’s interesting to reflect on B.C.’s early institution – against great odds – of true equality under the law – and that here is where modern Canada’s multicultural roots may lie.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.