It’s that time of year again. There’s a cold nip in the air – always a good time to stoke the fire and have a hot toddy. When I was young it seemed that our winters in British Columbia were colder. I remember skating on some of the frozen farm fields of Saanich with delightful names such as Panama Flats or Quick’s Bottom! My father tells me that when he was a young lad, he used to ice skate on Portage Inlet just outside the capital city.

Good story. But surely the best family story of cold times here on the Island came from my grandfather who was born at Christmas Hill in Saanich. I vividly remember each time he told the story that his eyes would light up along with his old meerschaum pipe – which I still have.

In 1916, Victoria was inundated with such a tremendous fall of snow (drifting to over 6 feet in height) the local military forces were called out. The army deployed 150 soldiers to assist the city that had come to a standstill – Victoria is the only Canadian city west of the Great Lakes to hold the record for so much snow in so little time.

My grandfather, aged 12 at the time, recalled the snow drifts were so deep. Many nearly covered the tops of telephone poles. My great grandfather, having experienced colder winters in 19th century BC, was nonplussed and simply got the horse and sleigh out.

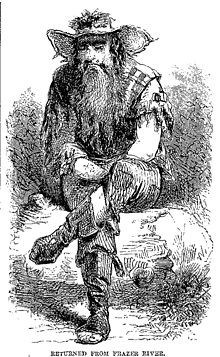

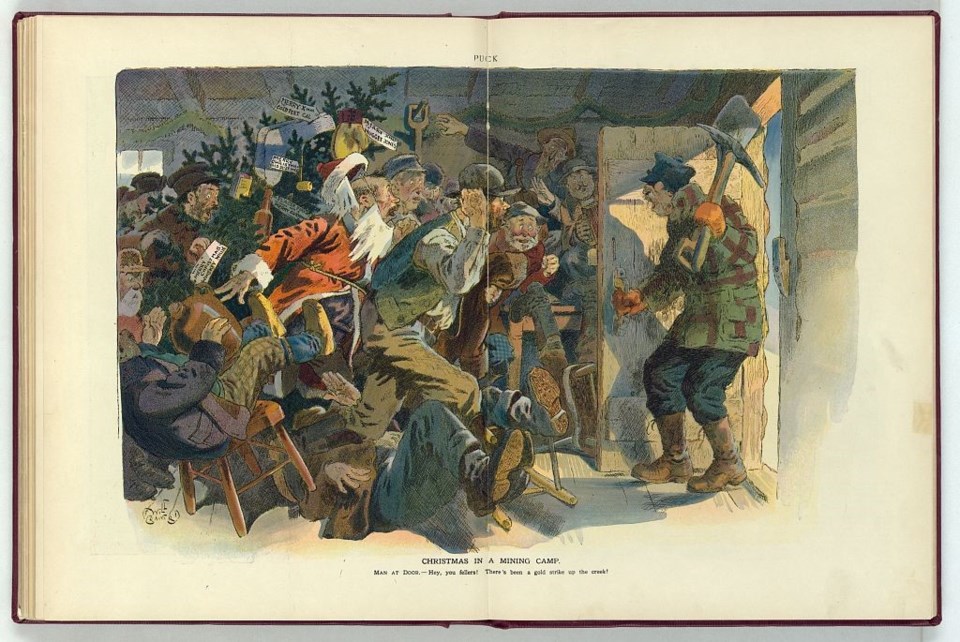

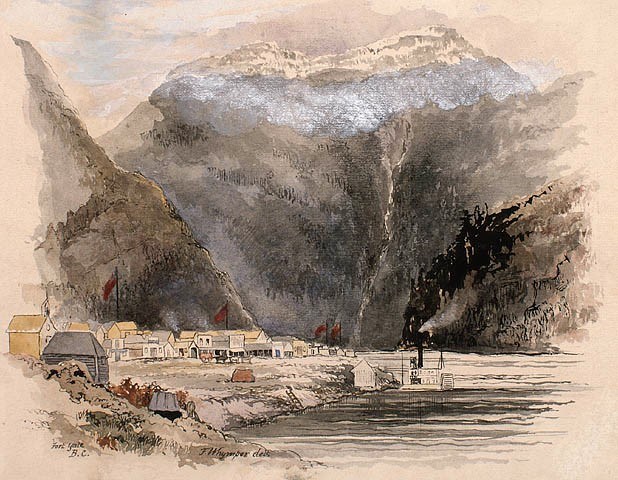

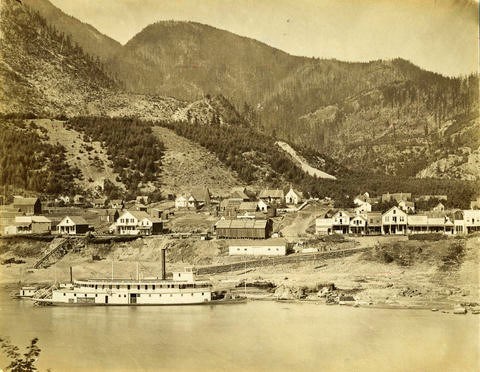

This got me thinking about what it must have been like in even earlier cold snaps. How would you survive? One story generally untold today is when the Fraser River froze up in the winter of 1858. Many gold miners were stranded, the steamboats largely unable to break through the ice and, as such, being the severe impetus for many a foreign-born miner forced to tramp through thick snows and occasionally not-so-thick ice.

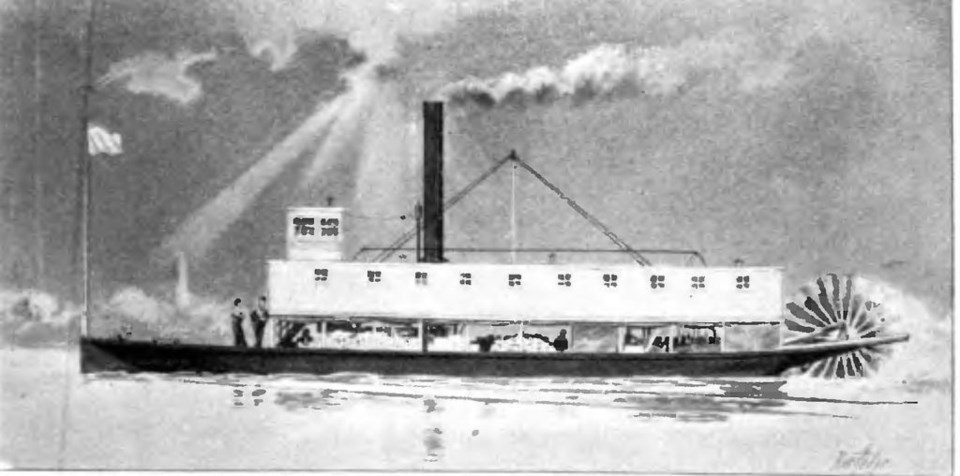

It is reported that more than a few plunged through into the icy river with their heavy packs and perhaps some weighty gold in a desperate attempt to reach far-distant Fort Langley on foot. Indeed there are accounts of miners found destitute and near the point of death, snow blinded and exhausted, clutching their Fraser River gold while warning away at gunpoint anyone who came close, for fear of losing their treasure. Only one riverboat captain in particular – “Bully” Wright – who had pioneered such travel on the Columbia River, made the determined decision to rescue as many goldseekers as he could. He rammed the steamboat through the ice, breaking it up, full steam ahead – apparently with tears streaming down his cheeks with the thought of so many lost in winter’s hard embrace.

As he steamed up the river, lost goldseekers were alerted to his approach by the continual blast of the ship’s steam whistle – can you imagine just how grateful those human souls were that help was on the way.

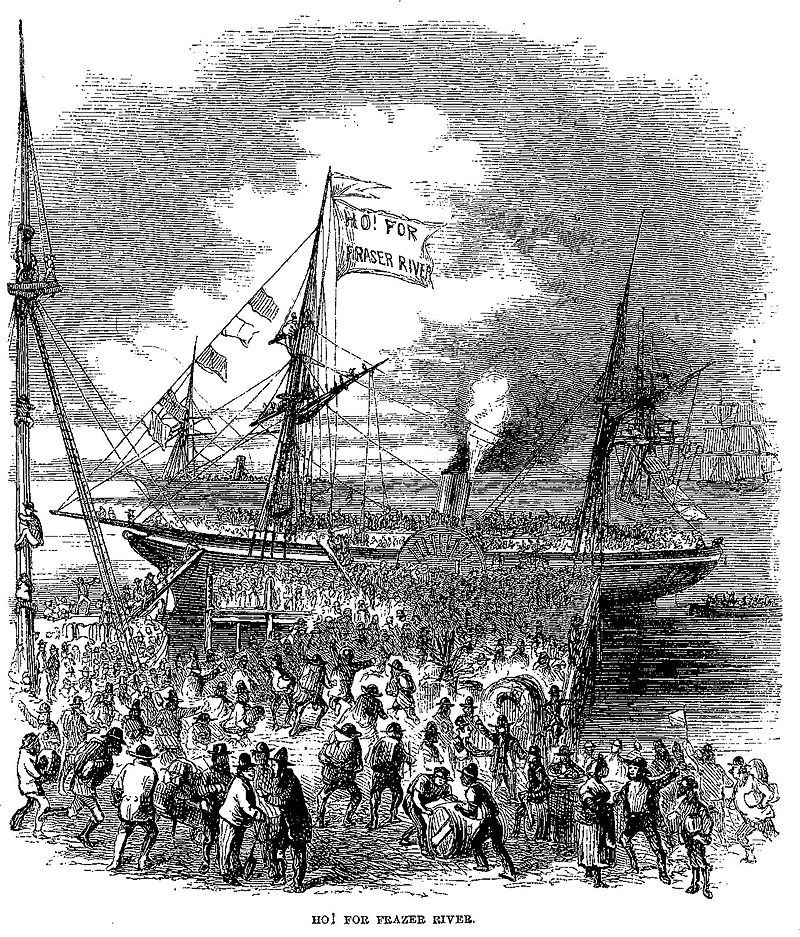

In a previous article I introduced one of the great storytellers of the British Columbia and California goldseeking era, the Halifax-born newspaperman David W. Higgins, who joined the Fraser River gold rush of 1858 from San Francisco during the height of the rush north.

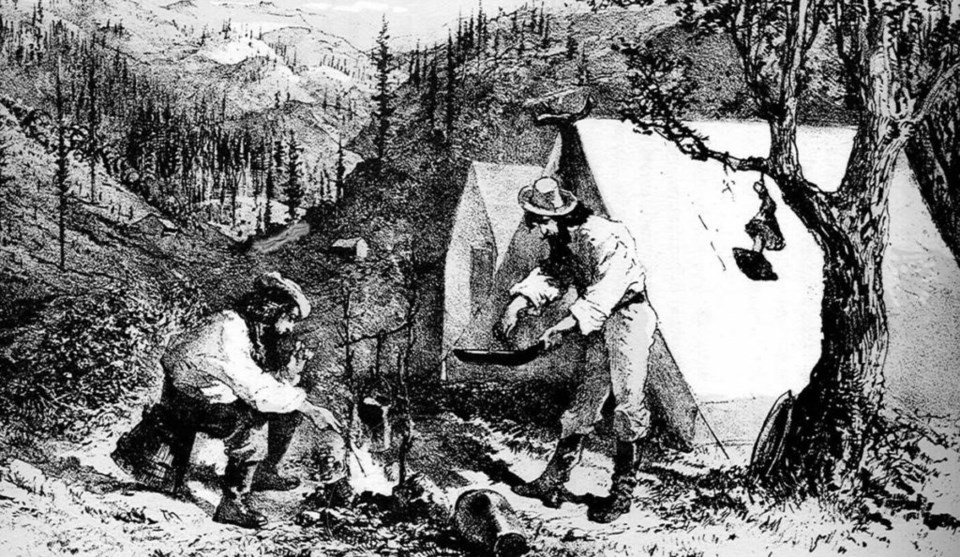

Higgins also told of this furious winter of 1858. He had decided to remain in Yale, and stay put while waiting for the return of both miners and the mining season in spring of 1859. Considering what happened for and to others, that was probably the smartest move.

Higgins remained hunkered down – except for one particular occasion, venturing out in the mountains above Yale.

I found myself drawn to this tale of just how harsh and unpredictable nature can be, the kind of pluck and zest for adventure many had – and how fortunate we are today for all the creature comforts of modern living.

In Higgins’ story, it was the day before Christmas. Provisions were low, as the frozen river prevented the arrival of steamboats like Captain Wright’s – provisioning lines were so incredibly important.

With no goose to cook for a celebratory dinner, they headed out over the Douglas portage trail that climbed Yale Creek into the hills behind Mount Lincoln. They knew of a road house about four miles up that apparently had been fattening some birds for the festive season. Higgins recalled:

The holiday season of 1858 found the people of the Fraser River town of Yale ill-prepared to face the rigors of a severe winter. Cold weather, which had set in unusually early, found many of the inhabitants still living in tents, and few occupied dwellings that were comfortable or storm and frost-defying. The lower river was closed by a sharp frost on the first day of December, and communication with the outer world, except to those who chose to risk their lives by walking over the ice, was suspended.

Supplies were scarce and high, and long before Christmas Day arrived people began to talk dismally of the prospects of a famine in the prime necessaries.

The prospect of famine was always a concern in this first year of the gold rush, so dependent on early steamboat technology to avert disaster. For goldseekers like Higgins, one could simply board such a ship from the docks of San Francisco to Victoria, then take another steamer from Victoria all the way to Yale – it was just that easy. But if the steamers stopped, not only would the flow of miners be impeded, but also the food, booze, and other essentials of life.

Higgins wrote:

When the day before Christmas dawned, the absence of the wherewithal for a seasonable dinner was seriously discussed. There was no poultry in town, but at Hedges' wayside house, some four miles up the Little Canyon, it was known that there were a small flock of hens and two geese that had been specially fattened for the festive occasion.

It was more in a spirit of adventure than anything else that four of us young fellows, Lambert, Talbot, Nixon and myself, proposed to tramp over the mountain trail to Hedges', and purchase half-a-dozen of his birds for our tables.

We started about two o'clock on the day before Christmas. The snow, which was about two feet deep on the town-site, gradually increased in depth as we ascended the trail, until we reached the summit, where the snow was three feet, rendering locomotion exceedingly difficult. It took us till six o'clock to reach Hedges', a trip that was usually made in one and one-half hours. We were completely exhausted when we came in sight of the smoke from the rude chimney, and saw the welcome glare of a light in the window as a beacon for -belated travellers.

Higgins and confreres had made their destination and were greeted with “a few drops of oh! be-joyful,” and “a bountiful repast of pork and beans” while the wind continued to pile snow in great drifts against the road house.

The storm continued throughout Christmas Eve as they sat by a welcoming fire and speculated on the chances of returning to Yale in time for Christmas Day.

“The landlord declared that it would be a physical impossibility for any person to pass up or down the river until the storm had abated,” declared Higgins, “but we Yaleites did not agree with him. We told him that we had promised to return to Yale by noon on Christmas Day with some of his fowls . . . . for I had a suspicion that Hedges, in discouraging our leaving, was anxious to retain us as guests until he had milked us of our last coin.”

With morning’s arrival the storm had not abated in the slightest and the temperature remained intensely cold, the road house now buried in further snow “and enormous drifts everywhere” but nevertheless “we four foolish young men proposed to start for home with the birds after an early breakfast.”

Several old miners who had returned from farther up the Fraser and had experienced huge challenges in making it to the road house thought them utterly mad.

One grey-haired prospector likened us to a lot of silly geese, and another said we ought to be sent to an asylum for idiots to have our heads examined. Another produced a tapeline, and with a solemn expression on his grim face proceeded to measure us. ‘What for?’ asked one of our party. ‘I'm a carpenter out of a job,’ he said, ‘and I shall begin to make four coffins the moment you pass out of sight, so that, when you are brought back stiff and stark, there will be nice, comfortable shells to put you in. Bill here (pointing to his mate) will proceed to dig four graves as soon as the storm is over.’

We all laughed heartily, but chaff and entreaties were futile. We discarded all advice, shouldered the poultry, and proceeded to pick our way up the mountain side, intending to follow a zig-zag trail. The snow was indeed deep, and as we advanced it grew deeper. We broke our way through several heaps fully six feet high. The wind howled dismally through the trees and underbrush, scooping up as it swept by great armfuls of snow, and piling it in fantastic shapes and drifts on all sides.

Once out of sight of the road house, the path had completely vanished with no discernible landmarks visible to guide them. Higgins next recalled looking at his watch:

We had started at eight o'clock, and it was now eleven. We had not made, according to my calculation, a mile; besides, we had no compass, and, being off the trail, it was impossible to tell whether we were going north or south.

We floundered on through the snow, which grew deeper and deeper as we ascended the mountain. Sometimes one of the party would step into a hole and disappear for a few moments. We would all stop, and, having hauled him out, would press on again in the hope of again recovering the lost trail. The cold grew sharper and the wind fiercer. We were fairly well wrapped in woollens. There was one fur coat in the party, and the wearer of it, young Talbot, who was not at all robust, seemed to feel the cold more keenly than the other three. Several times he paused as if unable to go on, but we rallied him and chafed him and coaxed him, until he was glad to proceed.

Another hour passed in the senseless effort to overcome the relentless forces of nature, and by that time we were four as completely used up and penitent men as ever tried to scale a mountain in the midst of a howling snowstorm, with the thermometer standing at zero. Talbot at last sank in a drift, panting for breath and weeping from exhaustion. We dug him out with our hands, and he tried to rise, but his strength was spent.

"Boys," he moaned, as he sank down again, "I am done. I can go no further. Leave me here. My furs may keep me warm until you can get help; but, at any rate, save yourselves if you can. I am not afraid to die, but I would rather not die on Christmas Day with my boots on."

"Fiddlesticks!" cried I. "What nonsense to talk of dying. We are all right. Only make another effort and we'll be at the summit. After that it will be all downhill and dead easy."

Talbot shook his head sadly, and continued, "Promise me you won't let me die with my boots on." Tears sprang from his eyes, and froze on his cheeks. He lay helpless and inanimate in the snow. Lambert and Nixon were strong and sturdy young men and as brave as lions; but they were greatly disheartened at the condition of our wretched companion. Besides, like me, they suffered severely from the cold, which had grown more intense as we proceeded.

All wished that we had listened to the expostulations of the people at the inn; but it was too late now for regrets— there was only room for action. Something must be done quickly or all would perish.

We divested ourselves of our packs, casting the fowls from us as if we hoped never to see another goose or chicken so long as we might live. The fowls sank in the new-fallen snow, and we saw them no more, and with them disappeared the wherewithal for a grand Christmas dinner which we were taking to our friends at Yale.

While we deliberated as to the best course to pursue, for it was as difficult to retrace our steps as it was to proceed, the snow having obliterated our footsteps, a sudden cry from Lambert attracted my attention. Pointing to Talbot, he exclaimed: "He has fallen asleep! Wake him up, in God's name, or he'll freeze to death!"

We seized Talbot and stood him on his feet. He was limp and helpless, and fell over again; his eyes were half-closed, and his breathing was so faint that when I put my face against his lips I could scarcely detect the slightest evidence that life still abode in that tired body. We rubbed his face, hands and ears with snow. Lambert and Nixon called him by name and begged him to speak. We pounded him on the back and stood him up again; but although he began to show faint signs of awakening, he was so far gone that he could not raise foot or finger to help himself.

Higgins quickly gathered a few pine limbs and with a knife hurriedly made kindling to start a small fire to sit Talbot by – all the while rubbing and pounding the young lad – and plying him with “a few drops of a cordial commonly known as H. B. Company rum.”

Talbot was revived but weak “and kept calling on his mother, who was thousands of miles away.” The foursome now decided to wait out the storm by the fire.

‘By Jove,’ said Lambert, ‘why didn't we think of it before? If we had kept those chickens we might have had a rousing Christmas dinner after all. We might have cooked them at this fire.’ But it was too late. We searched, but could not find the first feather. So we tightened our belts, consulted our flasks and tobacco pouches, and sat down by the fire. Talbot, having become rested by this time, showed no signs of falling asleep, but he was very weak and despondent.

About two o'clock the snow ceased to fall, and the wind gradually fell from a roaring blast to a gentle zephyr, and then died away altogether. Towards the south, the sky, which for two or three days had presented a hard, steely aspect, seemed to darken. Presently great heavy masses of clouds stole slowly along the eastern horizon, the cold lessened, and the temperature rose rapidly.

Then we knew that a Chinook wind had set in, that the back of the cold weather was broken, and that if we could but regain the lost trail we should be saved!

The problem for Higgins and friends was they could not find the trail – and nightfall was rapidly approaching. Lost in the mountains on Christmas Day, Higgins despaired that they must remain a further night “and tightened my belt another hole” for lack of any provisions. But a sudden welcoming sound pierced the snow-blanketed silence of their makeshift camp “and sent a thrill of joy through my tired and aching frame? ‘Is it the ring of a woodman's axe echoing through the canyon?’ I asked myself.” Higgins began to listen intently:

My heart almost stood still as I paused to listen. Then there broke full upon my ear the deep bay of a dog! It rolled up from the valley, and reverberated through the rocky depths, disturbing the awful stillness of the forest, and imparting to me hope and confidence at the prospect of a rescue.

I drew my revolver from my belt and fired five charges. I listened to the reports as they echoed through the forest and died away in the distance. Then—oh! thrice welcome sound! Never in all my life did a human voice seem so sweet in my ears as that which I heard utter almost at my feet:

‘Coo-ee!—coo-ee!’

I must have ‘Coo-eed-d’ in response, because again I heard clear and full and distinct a man's voice, as he shouted: ‘Where are ye, boys?’

‘Here,’ I cried, ‘this way.’

In another moment a great mastiff broke through an enormous drift and -barked loudly as if to encourage us, my companions having by this time become apprised that help was at hand. Talbot rose to his feet in his excitement and tried to call, but his voice died away, and he could not utter a word. He tried again and again, until his vocal chords at last limbered up, and he managed to burst the bonds of silence that his excitement had imposed upon him, and emitted a long, resonant:

‘Coo-ee!—coo-ee!’

We shouted again and again, and soon from the foot of the mountain there came back the answering call of many voices. The mastiff leaped as if with gratification at having found us, and led the way down the mountain side.

We plunged through snow that reached to our armpits, following the dog, and in a short time we came in sight of a large cabin with smoke curling from an ample chimney. As we approached a number of men came out to greet us. I paused to look and rubbed my eyes.

‘Is this a dream? Where are we, anyhow?’

Higgins was astonished as Hedges, the innkeeper of the road house they had left that morning, approached them. "I didn't expect to see you silly boys alive again," he said, "and I ought to have tied you up before I let you go out in the storm. Come in, anyhow, and have something, and then join us in our Christmas dinner, which is just about ready.”

Having escape a narrow brush with death, they were elated to sit down “to a roast of fowl and goose, and spent a jolly evening.” Apparently the only one disappointed in their safe return was the "carpenter out of a job" who rather grim-faced muttered, "Well, I'll be durned. It's just my luck. I'm out fifty dollars on your coffins." Higgins recorded that “Everyone laughed at this, but few besides ourselves understood how nearly our obstinacy and self-conceit had brought us to the ‘narrow home.’"

Back in Yale, everyone had given them up for lost. But two days on they straggled into town so thankful to have returned, and apparently rather annoyed that Hedges the innkeeper subsequently had gossiped to the Yale townfolk that “in all our wanderings and flounderings we had never been more than an eighth of a mile from the inn, having walked around in a circle after we lost the trail!”

Victoria pioneer Edgar Fawcett in his Reminiscences of Old Victoria (1912) wrote of the colder winters of the past, which he considered in later years “sadly lacking” and that “our climate has changed very much since then.”

His mark of a good winter was such that “Christmas, to be genuine, should be bright and frosty, with a flurry of snow, and this with walking exercise makes the blood flow freely, and makes one feel better able to enjoy the festive occasion.”

After his arduous trek during the winter of 1858, one wonders whether his old friend David Higgins would have agreed.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall on the "third great devil dance" in BC.

- Fred Braches on one of the most enduring legends in BC history - Pitt Lake Gold.

- Mike McDonald on a little more recent BC - and personal - history, as a teenage vote splitter.