I have a small suitcase packed and sitting by the door. My photos and family keepsakes have been loaded into my travel trailer, which has been towed to a lot in a safe(r) area to the north.

The area where I live is under a wildfire evacuation alert.

The small community of Lone Butte, five kilometres southwest, where I buy my farm fresh eggs and fill up with gas, has been evacuated. The Flat Lake wildfire is about 25 kilometres from my house.

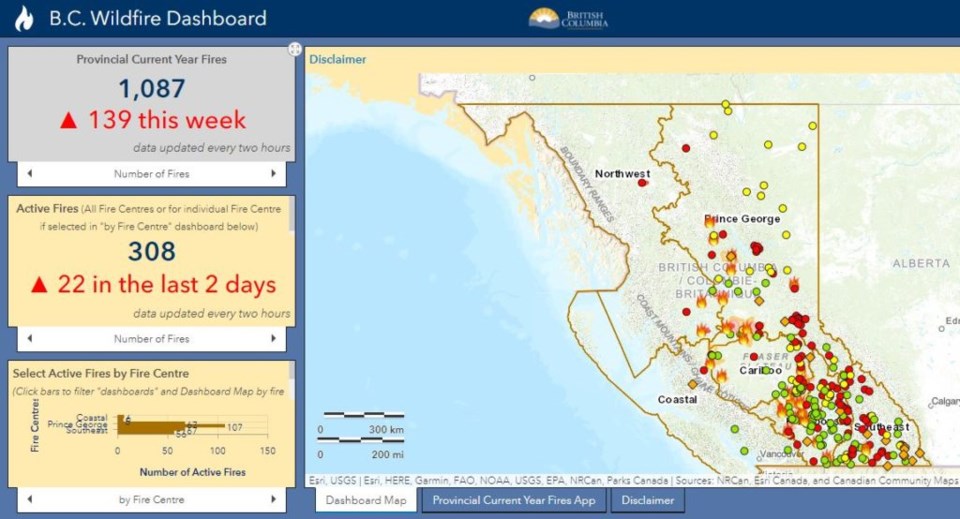

It is one of more than 300 wildfires burning in B.C. and it certainly seems like a state of emergency to me.

The 100 Mile and District Hospital has been evacuated and the town itself is under evacuation alert.

Twenty kilometres to the east, the Deka Lake fire is “being held,” but to the south four fires have merged around Young Lake and remain out of control.

The Sparks Lake fire is a dragon, raging north, and to the northeast, the Canim Lake fire, now 1,600 hectares, has forced evacuations.

The air is thick and filled with falling ash. Every time I leave my house I take my laptop and work equipment and the dog. I might not be able to come home again for some time.

The local Cariboo Regional District and the Thompson-Nicola Regional District are calling for a provincial state of emergency, as well as a handful of mayors and officials in affected regions.

We are in a drought in the hottest summer on record, and the town of Lytton has already been lost to flames.

States of emergency were declared for wildfires in 2017 and in 2018.

Local states of emergency have been declared in many of the affected regions but there is a chorus of calls for a provincial declaration, including an online petition.

It’s not clear, though, just what additional resources would be made available by such a provincial declaration.

Since 2017, there has been a great deal of public discussion about local and Indigenous knowledge as stewards of the land. The B.C. Wildfire Service is among the best in the world and they are working closely with local municipal and Indigenous leaders to determine the best plan of attack.

Putting out fires just because they’re burning is not an option any more. Preventing loss of life – as happening in Lytton – can be the only priority.

The extraordinary powers brought into play by declaring a state of emergency in years past – including a threat to take children from homes under evacuation order and military roadblocks in evacuated areas – were met with criticism for their heavy-handedness and lack of local input.

We’ve just come through an unprecedented global pandemic crisis in which many critics felt the province-wide approach had an outsized impact on local businesses in small communities with much less risk.

The provincial government has said that such extraordinary powers were not necessary during the 2003, 2017, or 2018 fire seasons and “if a provincial emergency was not declared during those events, it would have not changed our response in any way.”

A provincial state of emergency will be declared, the province says in a statement, “if, and when, it’s required.”

"We're confident that every resource that can be mustered is being mustered. A state of emergency's not required to do that," Premier John Horgan told reporters during a news conference from the Kamloops fire centre.

The premier and Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth say they are acting on advice from officials at B.C. Wildfire Service.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow for the regions where thousands of evacuees are understandably wondering whether more resources might be available.

It’s certainly no time for political games for those of us choking on smoke.

As these extraordinary weather events become ever more common – crushing winter storms, spring flooding, summer droughts and record-setting heatwaves – this province will need to adjust its expectations and reactions to such events.

Because it’s going to happen again. And again. And again.

These are no longer extraordinary events.

Of course, it’s very early in the hottest, driest summer of our lifetimes. The province will, unfortunately, have many opportunities before wildfire season is over to change its mind on a state of emergency.

Dene Moore is an award-winning journalist and writer. A news editor and reporter for The Canadian Press news agency for 16 years, Moore is now a freelance journalist living in the South Cariboo. Moore’s two decades in daily journalism took her as far afield as Kandahar as a war correspondent and the Innu communities of Labrador. She has worked in newsrooms in Vancouver, Montreal, Regina, Saskatoon, St. John’s and Edmonton. She has been published in the Globe and Mail, Maclean’s magazine, the New York Times and the Toronto Star, among others. She is a Habs fan and believes this is the year.

SWIM ON:

- Dene Moore last wrote that an acute labour shortage is made worse when young people have fewer options to get to work.

- Jody Vance was also uncomfortably close to a wildfire. How close? One fellow passenger asked if it was a volcano.

- Ten days ago, the provincial government dismissed calls to declare a state of emergency. Things have not improved.