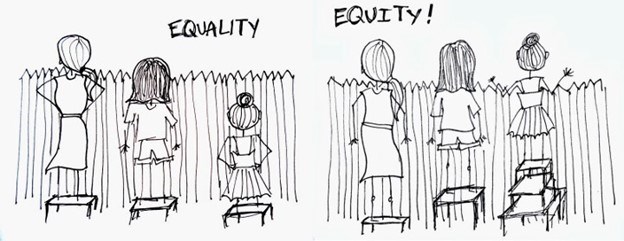

Equal does not mean equitable.

The next time B.C. voters go to the polls it is very likely the electoral map of this province will look different than it does today.

We are fortunate to have an independent commission tasked with reviewing regularly the boundaries of our political ridings. Every province has such a commission, as does the federal government, to take out of political hands the ability to “gerrymander” riding boundaries to favour the parties in power.

The B.C. commission will be appointed this fall and deliver recommendations to the legislature within 12 months.

Anticipating the review, the NDP government introduced changes to the Electoral Boundaries Commission Act this month, including the removal of a provision introduced by the then-BC Liberal government in 2014 that barred the commission from reducing the number of seats in three rural ridings hit hard by population loss. Under the 2014 amendment, the North, Central Interior and Columbia-Kootenay regions cannot have fewer than 17 seats.

In announcing the changes to the Act, the Ministry of the Attorney General said that restriction “made B.C. an outlier.”

“Most other provinces do not have these kinds of regions,” the ministry said in a news release.

Not true.

Many provinces have some measure of protection for rural communities. Indeed, Nova Scotia’s commission says its mandate is to ensure “effective” representation, specifically for Acadian, Black and Mi’kmaq populations.

“We acknowledge that voter parity may limit the voices of minority voters. This allows for the creation of electoral districts that contain fewer voters to allow for those minorities to be represented effectively in the legislative assembly,” the Nova Scotia commission said in its most recent report.

Federally, Greater Toronto has 10 per cent of the Canadian population. Should the GTA get 10 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons? Imagine the Constitutional crisis if Atlantic Canada, with about six per cent of the population, was reduced to that proportion of federal ridings? And what of the North, whose combined population is less than one per cent of the Canadian total, stretched over 39 per cent of the Canadian land mass?

The announcement of these changes weighs heavily in favour of population-based distribution of ridings. Population is mentioned no fewer than eight times in the news release.

“The commission will be asked to achieve through recommendations – to the extent possible – the fundamental democratic principle that everyone’s vote should be reasonably equal in weight in choosing elected officials,” it says.

“Equal in weight” is another way of saying based on population. Of course, it comes to mind that the governing party has a primarily urban caucus.

It doesn’t bode well for B.C. beyond the 604. Then again, that’s why the commission is independent.

We can hope they put more weight on the opinion of the country’s highest court, which has soundly rejected the “one person, one vote” principle espoused by representation-by-population schemes.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees all Canadians “effective representation,” the Supreme Court of Canada found in the 1991 Carter decision out of Saskatchewan.

“Geography, community history, community interests and minority representation may need to be taken into account to ensure that our legislative assemblies effectively represent the diversity of our social mosaic,” the court wrote.

Equality and equity are not the same thing.

Arguably, the voters furthest from the halls of power have greatest need for a voice within. The collapse of community media doesn’t help, leaving the public discussion largely the purview of urban-based pundits with no idea and no interest in rural British Columbia.

A reduction in the number of voices speaking for B.C. outside of Greater Vancouver and Victoria will do nothing to help the growing divide between the urban and rural voters of the province.

After the commission’s initial report is delivered there will be six months of public consultation. Sharpen your pencils, rural B.C., or forever hold your peace.

Dene Moore is an award-winning journalist and writer. A news editor and reporter for The Canadian Press news agency for 16 years, Moore is now a freelance journalist living in the South Cariboo. Moore’s two decades in daily journalism took her as far afield as Kandahar as a war correspondent and the Innu communities of Labrador. She has worked in newsrooms in Vancouver, Montreal, Regina, Saskatoon, St. John’s and Edmonton. She has been published in the Globe and Mail, Maclean’s magazine, the New York Times and the Toronto Star, among others. She is a Habs fan and believes this is the year.

SWIM ON:

- On Mother's Day, Dene Moore wrote there was no better time to take stock of just how hard the pandemic has been on moms.

- Daniel Marshall looked back to BC's first urban/rural political divide.

- As Canadians flee cities, Sylvain Charlebois thinks rural areas might just get their mojo back.