I remember the first time I had a good look at the fabled Golden Gate Bridge.

It was the mid-1980s and fortune struck when a friend invited me to spend the summer in California. There we were, on the beach below the historic Presidio in an immense crowd of San Franciscans celebrating the 50th anniversary of that hugely symbolic bridge – a gateway marking the entrance to a harbour jam-packed with gold rush history.

Legendary crooner Tony Bennett was there, just off the beach (singing, “I left my heart, in San Francisco. . .”), and the sky had been so warm and blue as to question Mark Twain’s observation that the coldest winter he ever experienced was the summer he spent in San Francisco.

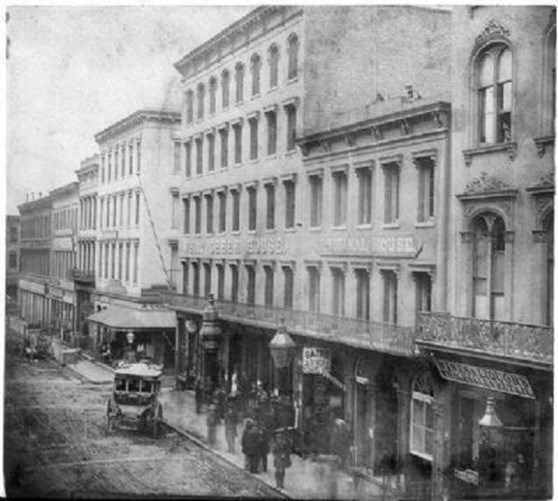

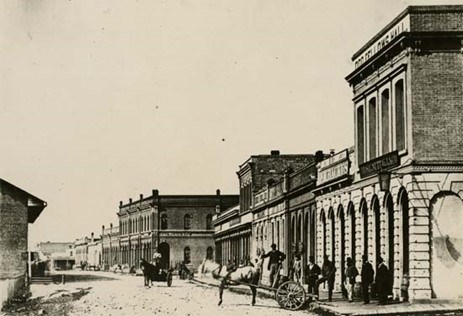

That gorgeous long summer was my chance to explore firsthand the historic connection between British Columbia and the Golden State. Wandering around old San Francisco felt familiar – after all, the 1850s iron-façade buildings on Wharf Street in Victoria were manufactured in California.

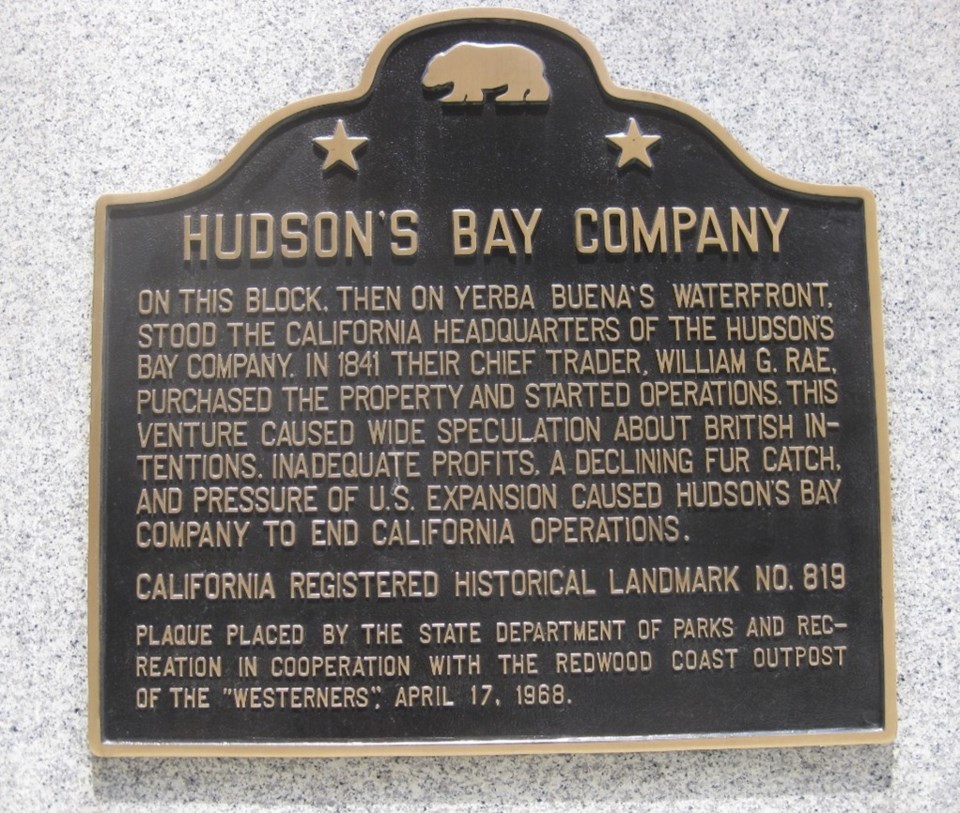

My mission was to locate two historic markers. First, the site of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s California headquarters established in 1841, when San Francisco was still known as Yerba Buena, and not part of the United States.

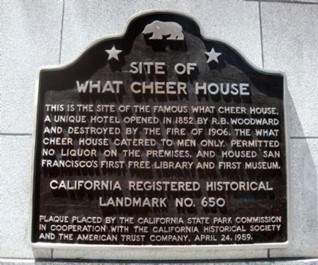

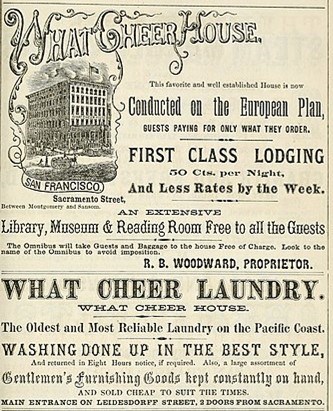

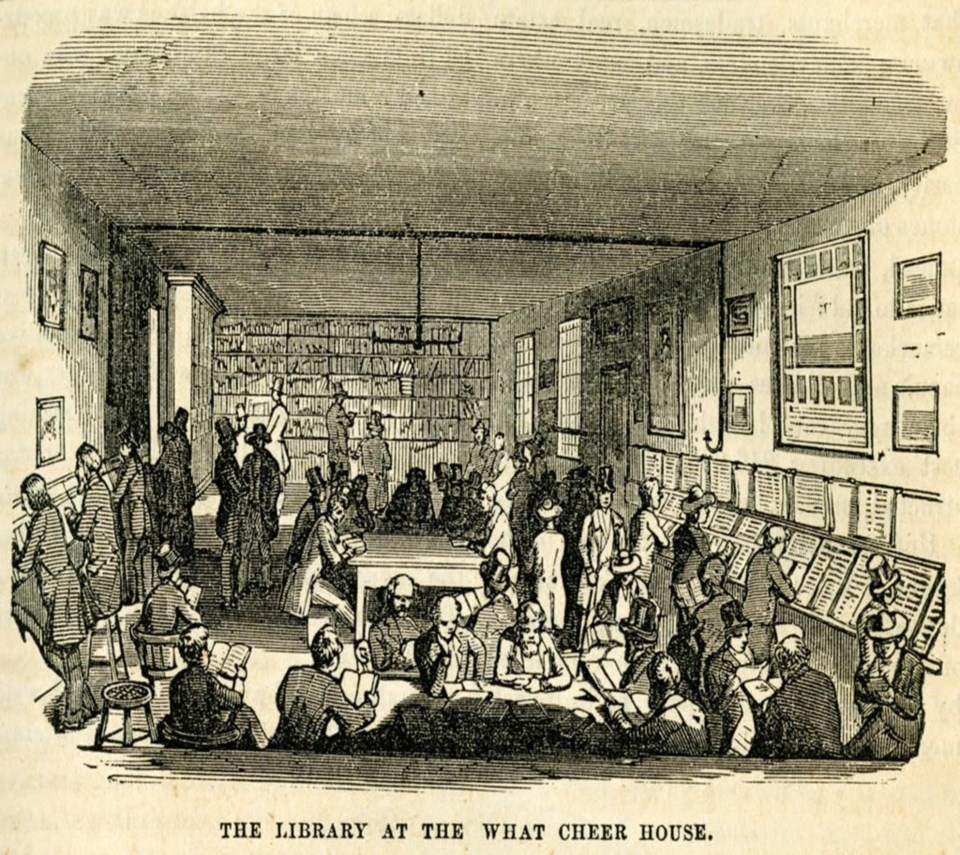

But more particularly, I wanted to see the location of a well-known hotel that once existed about 400 feet away from the HBC store, a hotel established in 1852 with the city’s first public library and reading room, known as the “What Cheer House.”

Standing there that day I wondered just how many gold seekers must have stayed here? Who read in this first library during the time of the Fraser River exodus (the 3rd great mass migration of gold seekers in human history)?

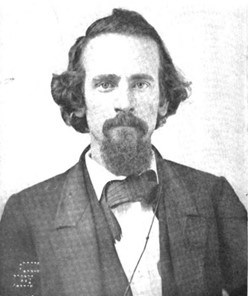

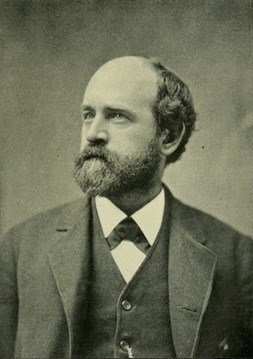

Here is the singular story of one such would-be miner: Henry George, subsequently “the most popular American economic thinker of the 19th century” – a populist before populism had a name. The word “populism” – coined in 1890 – meant opposition to a monopoly on wealth held by businessmen and bankers, and this is a rags-to-riches story of the gold rush of a very different sort!

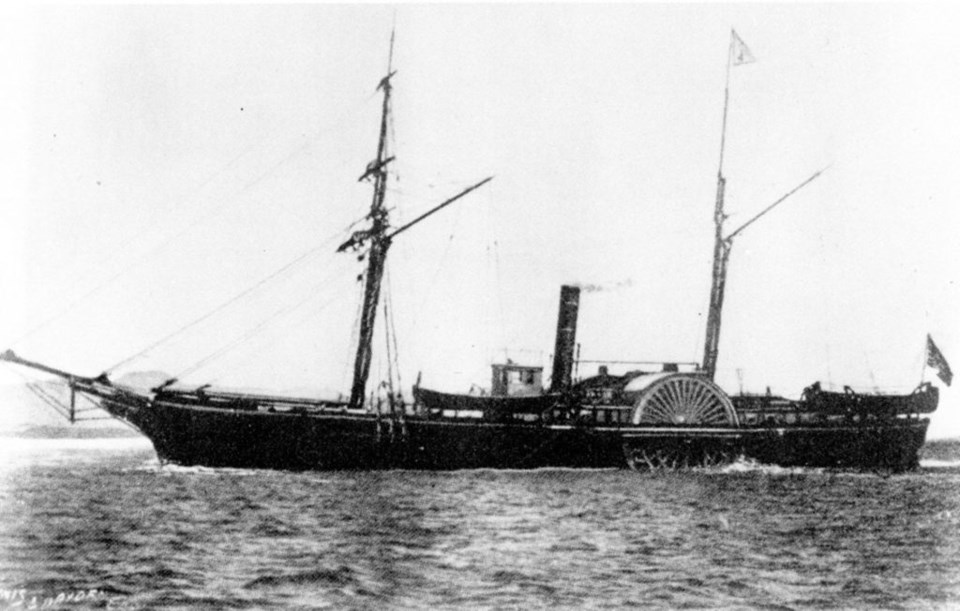

A young 18-year-old typesetter, Henry George traveled from Pennsylvania via the Strait of Magellan aboard the USS Shubrick. He arrived in California in late May of 1858 after a journey of 155 days, and just as the Fraser River Excitement was peaking.

About an hour after the Shubrick anchored, the ship was visited by Henry George’s cousin, James George, a bookkeeper for the retail clothing firm of J. M. Strowbridge & Company, who had already traveled to California. Work prospects for young Henry were in rather short supply, and with increasing news of the Fraser gold excitement, he made his decision to travel north and seek his fortune. His son Henry George Jr. (later a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York) wrote a biography of his famous father entitled The Life of Henry George (1900), in which he described that decision.

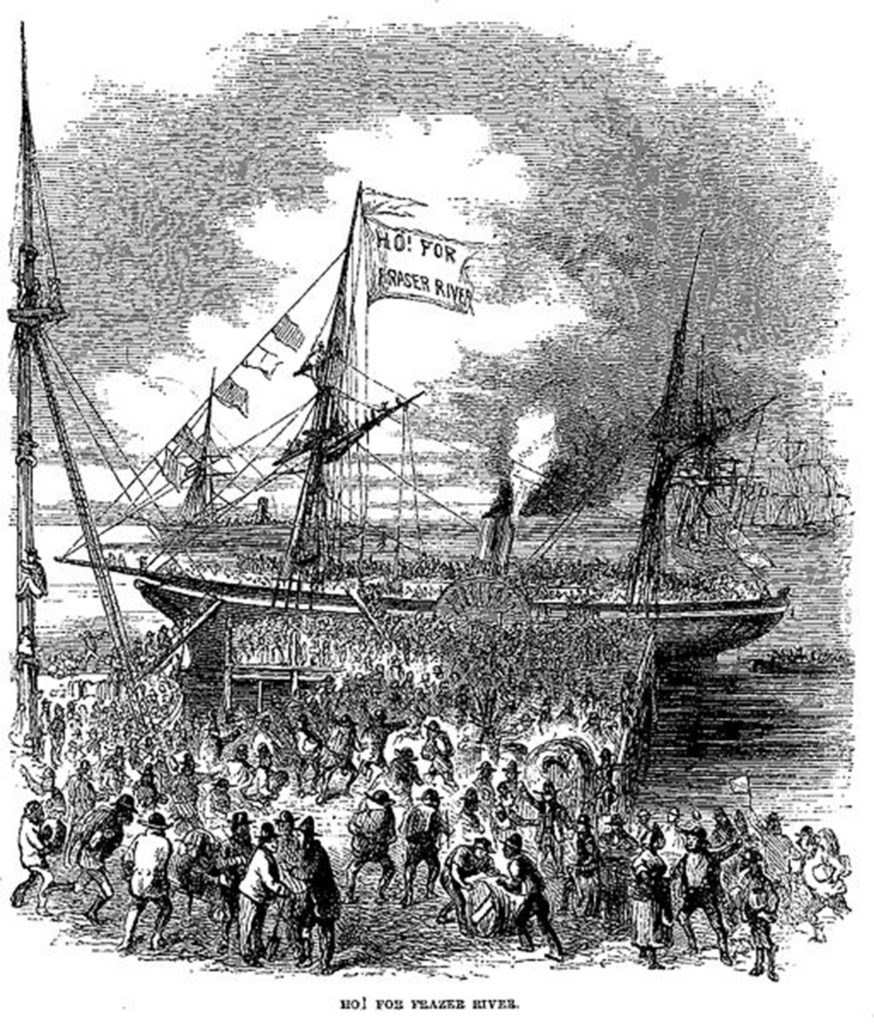

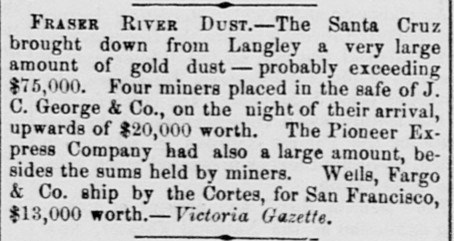

For in June [1858] had come the thrilling news of large gold discoveries just over the American line, in the British possessions, on the Frazer River, not far from its mouth. There was much excitement in San Francisco, especially among that multitude of prospectors and adventurers, who, finding all the then known placer lands in California worked out, or appropriated, and not willing to turn to the slow pursuits of agriculture, had gathered in the city with nothing to do. A mad scramble for the new fields ensued, and so great was the rush from this and other parts that fifty thousand persons are said to have poured into the Frazer River region within the space of a few weeks. Indeed, all who did not have profitable or promising employment tried to get away, and the Shubrick’s log shows that most of her officers and crew deserted for the gold fields.

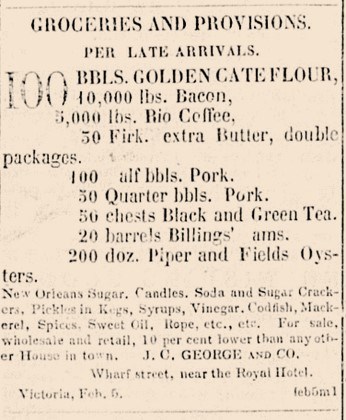

Though Henry’s cousin had been doing well with the clothing house, like thousands of others got swept up by the Fraser Fever and “thought he saw a chance for a fortune in the sale of miner’s supplies,” entering into partnership to establish a store in Victoria.

In Henry’s case the proposed plan was for him to head to the Fraser goldfields and, in the event of his mining prospects falling short, his cousin promised employment as a clerk in the new Victoria-based store.

“Henry George’s hopes burned high,” recorded his son, and he wrote home to Philadelphia, 15 August 1858, of his “golden expectations” that were met with dismay by his mother.

I think this money-making is attended with too many sacrifices. I wished it all in the bottom of the sea when I heard of your going to Victoria, but since it had been explained to me I feel better. . . I shall never feel comfortable until you are settled down quietly at some permanent business. This making haste to grow rich is attended with snares and temptations and a great weariness of the flesh. It is not the whole of life, this getting of gold. When you write explain about the place and how you are situated. Then we will look on the bright side.

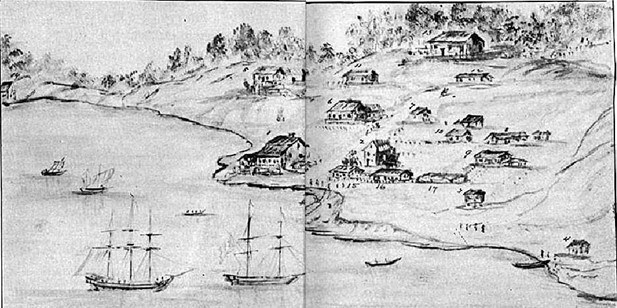

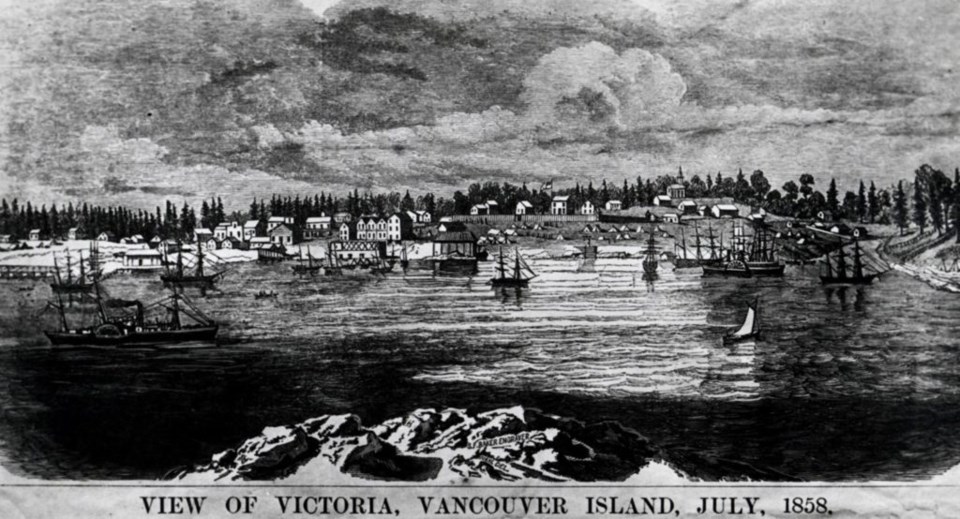

Henry George sailed through the Golden Gate out of San Francisco, employed as a seaman aboard “a topsail schooner,” landing in Victoria at the height of the rush north. The old HBC fort “suddenly swelled in population, until it was estimated that at times ten thousand miners, in sheds and tents, gathered about the more substantial structures.”

But George’s arrival at Victoria was the most inauspicious time to continue towards the goldfields, as the “melting snows on its great mountain water-sheds swelled high its volume, came tearing down its long, twisting course and rushed through its rocky gorges like a roaring flood of destruction, earning the name sometimes given it – ‘The Terrible Frazer.’”

The goldfields had come to a standstill, thousands of gold seekers left waiting for the river to drop before mining operations could resume. So George subsequently found employment in his cousin’s newly-established miner’s emporium on Wharf Street.

The store was apparently a one-story rough wooden structure with a makeshift loft situated beside the “Victoria Hotel” and facing the Inner Harbour. Henry George worked very hard there, sleeping in the loft during these tumultuous times. “He fastened a note outside the street door inviting customers who came out of the regular hours to ‘Please give this door a kick.’” In a letter to his sister, 6 December 1858, he described further the conditions.

You innocently ask whether I made my own bed at Victoria. Why, bless you, my dear little sister! I had none to make. Part of the time I slept rolled up in my blanket on the counter, or on a pile of flour, and afterwards I had a straw mattress on some boards. The only difference between my sleeping and waking costumes was that during the day I wore both boots and cap, and at night dispensed with them.

After some months of hard toil it appears that George had enough of the place. He left his cousin’s shop to go live in a tent with fellow San Franciscan George Wilbur who was determined to make a second attempt in the Fraser goldfields, “but before they could set off they were daunted by stories of failure that returning miners were bringing down.” The lure of gold had tarnished and they abandoned the project.

George’s “golden expectations” were now dashed, and without employment decided to return to San Francisco, borrowing passage money from George Wilbur and others. Wilbur stated of his destitution that:

He had no coat; so I gave him mine. An old fellow named Wolff peddled pies among the tents, and thinking that Harry would enjoy these more than the food he would get aboard the ship, we bought six of them, and as he had no trunk, we put them in his bunk, and drew a blanket over them so that nobody would see them and steal them. He wrote me from San Francisco when he got down that first night out he was so tired that he threw himself down on his bunk without undressing, and that he did not think of the pies until the morning, when he found that he had been lying on top of them all night.

George had left Victoria “dead broke” along with a borrowed coat and six squashed pies. It seems his northern adventure had not amounted to anything, but for some key facts. “Arriving in Victoria in August 1858, Henry George observed conditions which formed the genesis of his economic theories that would garner worldwide acclaim.”

Having returned to California his own economic conditions, while improving, had been a mixed bag – even reduced to begging at one point in the 1860s – but for two key developments.

First, his experience as a typesetter landed him a job and started his career in newspapers and as a writer. Second, George’s income now provided the kind of lodgings beyond the tent or shack he inhabited in Victoria.

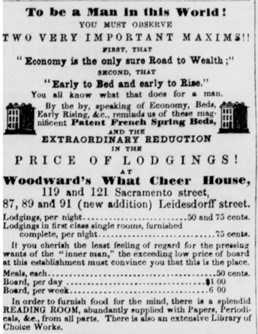

The next letter home to his sister, 6 December 1858, announced his sense of prosperity after the hardship endured in British Columbia: “I am boarding now, and have been for the past two weeks in the ‘What Cheer House,’ the largest, if not the finest, hotel in the place. I pay $9 per week and have a beautiful little room and first rate living. I get $16 per week the way I am working now, but will soon strike into something that will pay me better.”

The What Cheer House advertised not only “an extensive library of choice works”, but that “To be a man in the world” one must observe that “Economy is the only sure Road to Wealth.”

Apparently, the What Cheer House had several hundreds of books in its library, including some economic works such as Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations. It was here that George’s “solid reading was begun in this little library.” In fact, when George continued to be down on his luck, he “spent much of his time when out of work in that little room and that he had read most of the books.”

George made good use of this library even while experiencing a rather desperate poverty at times. By 1865 he had become a journalist and founded the San Francisco Daily Evening Post (1871-1875) where he became a critic “of speculation in public lands, the illegal actions of monopolies, and the exploitation of new Chinese immigrants in California.” He proposed economic reforms, public ownership of utilities that included such industries as railroads and the telegraph system, popularized the "single-tax" reform movement, though never embraced the ideology of socialism.

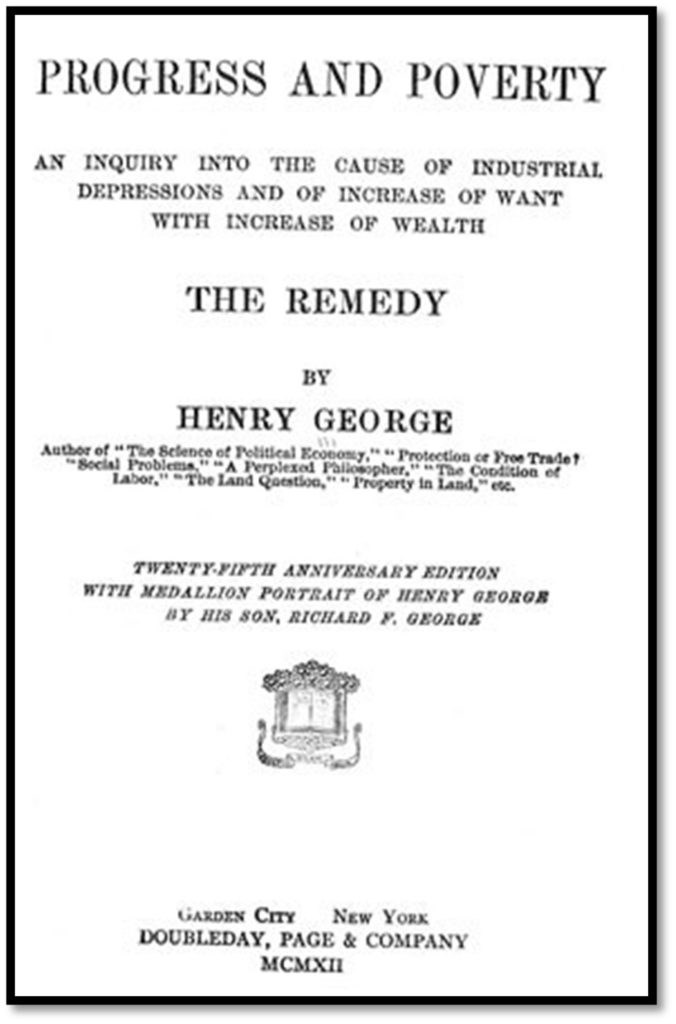

His major work was Progress and Poverty (1879), which he infused with his strong moral passion for justice and his hatred of poverty, like he had experienced in British Columbia.

Progress and Poverty was George's first book, which sold several million copies, exceeding all other books sold in the United States except the Bible during the 1890s. In this volume George stated of the 19th century gold rushes:

There is no mystery as to the cause which so suddenly and so largely raised wages in California in 1849, and Australia in 1852. It was the discovery of placer mines in unappropriated land to which labour was free that raised the wages of cooks in San Francisco restaurants to $500 a month, and left ships to rot in the harbour without officers or crew until their owners would consent to pay rates that in any other part of the globe seemed fabulous. Had these mines been on appropriated land, or had they been immediately monopolised so that rent could have arisen, it would have been land values that would have leaped upward, not wages.

Progress and Poverty has been described as “a treatise on the questions of why poverty accompanies economic and technological progress and why economies exhibit a tendency toward cyclical boom and bust.”

“We see it all over the world,” stated George, “in the countries where land is high, wages are low, and where land is low, wages are high. In a new country the value of labour is at first at its maximum, the value of land at its minimum. As population grows and land becomes monopolised and increases in value, the value of labour steadily decreases.”

Less well known was the inspiration for these social and economic theories: George’s experience as a gold seeker in the Fraser River excitement of 1858. More than 30 years after his time in Victoria, George gave a speech in San Francisco (4 February 1890) that traced “the genesis of his thought on social questions.”

“I came out here at an early age, and knew nothing whatever of political economy,” stated George. “I had never intently thought upon any social problem. One of the first times I recollect talking on such a subject was one day, when I was about eighteen, after I had come to this country, while sitting on the deck of a topsail schooner with a lot of miners on the way to the Frazer River.” George continued:

I remember, after coming down from the Frazer River country, sitting one New year’s night in the gallery of the old American theatre – among the gods – when a new drop curtain fell, and we all sprang to our feet, for on that curtain was painted what was then a dream of the far future – the overland train coming into San Francisco; and after we had shouted ourselves hoarse, I began to think what good is it going to be to men like me – to those who have nothing but their labour? I saw that thought grow and grow. We were all – all of us, rich and poor – hoping for the development of California, proud of her future greatness, looking forward to the time when San Francisco would be one of the great capitals of the world; looking forward to the time when this great empire of the west would count her population by millions. And underneath it all came to me what that miner on the topsail schooner going up to Frazer River had said: ‘As the country grows, as people come in, wages will go down.’”

It is said that during his lifetime, George became the third most famous person in America, behind Thomas Edison and Mark Twain. He was one of the most important voices of the Progressive Era; his supporters included Leo Tolstoy, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, and John Dewey. The ideology of “Georgism” dominated the social and economic thinking of the day – and many of his insights seem prophetic today. About 150 years ago, George spoke of a rising populism that had swept the country:

The most ominous political sign in the United States today is the growth of a sentiment which either doubts the existence of an honest man in public office or looks on him as a fool for not seizing his opportunities. That is to say, the people themselves are becoming corrupted. Thus, in the United States today is republican government running the course it must inevitably follow under conditions which cause the unequal distribution of wealth. Where that course leads is clear to whoever will think. As corruption becomes chronic; as public spirit is lost; as traditions of honor, virtue, and patriotism are weakened; as law is brought into contempt and reforms become hopeless; then in the festering mass will be generated volcanic forces, which shatter and rend when seeming accident gives them vent. Strong, unscrupulous men, rising up upon occasion, will become the exponents of blind popular desires or fierce popular passions, and dash aside forms that have lost their vitality. The sword will again be mightier than the pen, and in carnivals of destruction brute force and wild frenzy will alternate with the lethargy of a declining civilization.

The predication is all the more remarkable, considering its foundations came from a young lad who had experienced the chaotic, frenzied Fraser River Excitement of 1858 firsthand, followed by an informal education in the What Cheer House hotel. Clearly, this is a very different sort of rags-to-riches story! And more to the point, this is a story that once again places British Columbia’s early history – before the coming of transcontinental railways – squarely within the North-South world of the expansive Californian mining frontier.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.

Claiming the Land has achieved a rare and possibly unique feat in BC History by winning three major book awards: the Canadian Historical Association’s 2019 CLIO PRIZE for best book on B.C.; the 2019 Basil-Stuart-Stubbs Prize for outstanding scholarly book on British Columbia, administered by UBC Library; and the 2019 New York-based Independent Publishers’ Book Award (Gold Medal for Western Canada).

SWIM ON:

- Daniel Marshall's last story also focused on the connection between 1850s British Columbia and California - specifically, the famous Bonanza Kings.

- How strong were the connections between BC and California? Daniel's first piece for The Orca was entitled British California. And it's a history piece, so it's still good. Don't miss it.

- Things have changed - but there are still connections. Sylvain Charlebois looked at the effect California wildfires would have on BC grocery bills.