Since its inception, British Columbia has had to contend with trade wars and the threat of tariffs. These issues continue to command press headlines, but they’re nothing new.

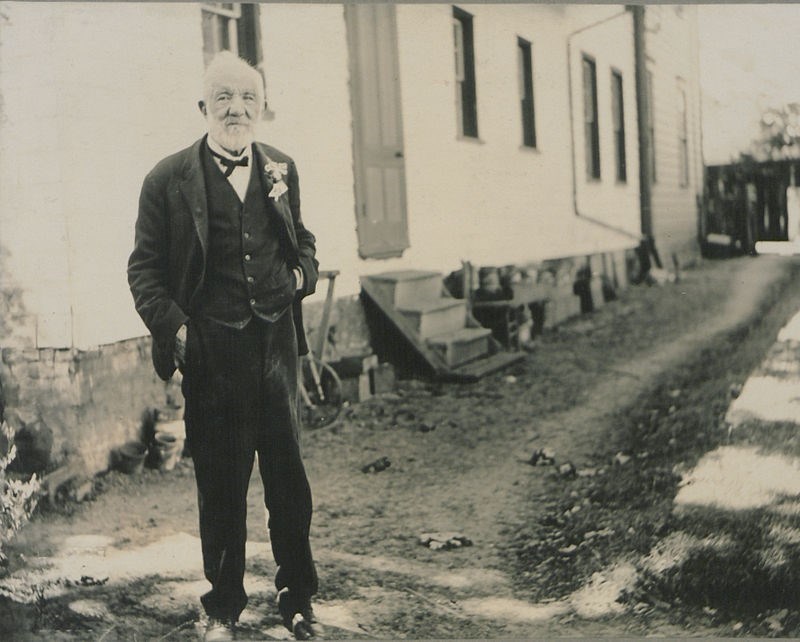

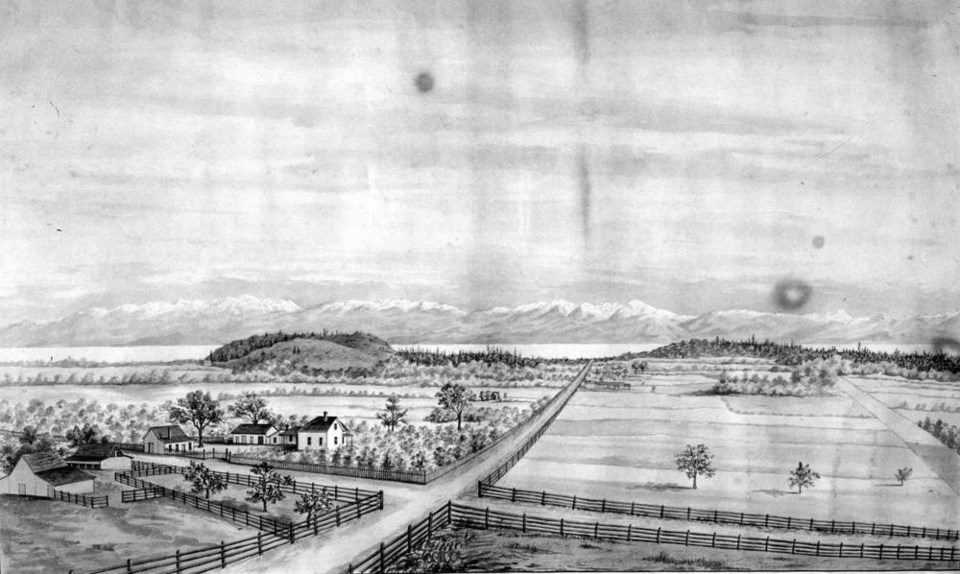

My own family were farmers who first settled in 1860 at Swan Lake, below Christmas Hill in Saanich, Vancouver Island. Since the days of the 1858 Fraser gold rush, there had always been the threat of cheap California produce flooding the BC market. So the old BC colonial tariff structure encouraged by Governor James Douglas sought to protect local agricultural interests – like those of my family.

All this changed dramatically once BC joined Confederation in 1871. From there, a period of harmonization with Canada’s federal policies then commenced. One such policy was the introduction of the Canadian tariff structure to the newly admitted province.

This is perhaps one of the most significant, yet neglected, topics in BC history.

The introduction of the tariff instilled particular misgivings amongst BC’s agricultural and certain commercial interests – which then as now, fell along established political fault lines. The same rural interests that Premier Amor De Cosmos represented in Victoria District, versus Premier John McCreight’s commercially oriented Victoria City.

Extensive political debates before, during, and after Confederation talks divided legislators and the public alike into separate camps throughout the first three sessions of the B.C. Legislative Assembly, primarily on the fundamental question of tariff protectionism.

Concern over the possible impact of the eastern trade scheme on the fledgling B.C. economy was exemplified in the minutes of the “Debate on the Subject of Confederation With Canada.” Extensive deliberation on this issue alone raised tariffs to a status equal to, if not greater than, more-scrutinized demands for responsible government and a transcontinental rail link with Canada.

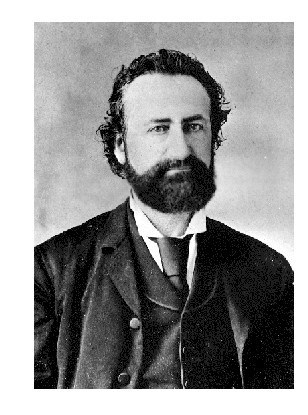

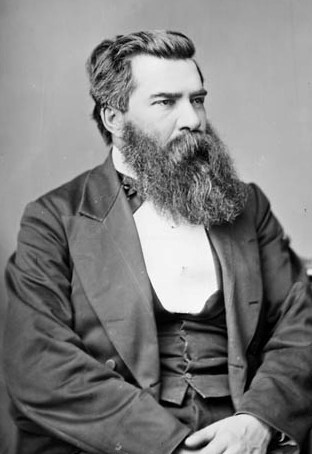

Dr. John Sebastion Helmcken – a subsequent BC Father of Confederation – (and who use to ride his horse-drawn buggy out to our old farm) was of the view:

I feel perfectly sure, Sir, that if Confederation should come, bringing with it the Tariff of Canada, not only will the farmers be ruined, but our independence will be taken away; it will deprive our local industries of the protection now afforded them, and will inflict other burdens upon them; it will not free trade and commerce from the shackles which now bind them, and will deprive the Government of the power of regulating and encouraging those interests upon which the Colony depends.

There can be no permanent or lasting union with Canada, unless terms be made to promote and foster the material and pecuniary interests of this Colony. . . I am opposed to Confederation, because it will not serve to promote the industrial interests of this Colony, but on the contrary, it will serve to ruin many, and thus be detrimental to the interest and progress of the country.

I say that Confederation will be injurious to the Farmers, because protection is necessary to enable them to compete with farmers of the United States. The [Canadian] Tariff and Excise Laws do not supply that.

Amor De Cosmos and his newspaper the Victoria Daily Standard were consistent advocates of a modified Canadian tariff that extended protection to farmers. From the beginning of his political career, De Cosmos had advocated Confederation with Canada and the introduction of responsible. Yet he further believed that protection for the agricultural interests of the colony were not only “the very keystone of Confederation,” but of more consequence than responsible government.

In negotiations with Canada, B.C.’s final compromise really did nothing to solve the problem. Article Seven of the Terms of Union stated that the old B.C. tariff should “continue in force in British Columbia until the railway from the Pacific Coast and the system of railways in Canada are connected unless the Legislature of British Columbia should sooner decide to accept the Tariff and Excise Laws of Canada.”

Article Seven effectively postponed any decision on modified tariffs, but awarded BC the right to accept the Canadian tariff in advance of a completed rail connection with the East. BC’s entry was secured, and difficult decisions like tariffs delayed so as not to break the Terms of Union Treaty.

Future provincial legislators were henceforth given the opportunity to campaign for the immediate introduction of the Canadian tariff and the further possibility of electing a legislative body more favourably inclined to free trade principles.

Article Seven of the Terms of Union provided the roots of polarization. It had a central role in setting the tone of the first provincial electoral contest between those seeking an immediate reduction in commodity and other prices, and those who favoured adequate protection for fledgling agricultural and industrial pursuits.

In the first provincial election of 1871, the early-acceptance proviso of Article Seven caused quick action from those politicians who adopted a pro-Canadian tariff position, most often as the main plank in their platform.

De Cosmos hoped for a majority return of those who supported a modified tariff. But the pro-Canadian tariff forces appeared to have won the day – or at least, the election. From a total of 25 MLAs, the cabinet of John Foster McCreight was cemented not so much by shared birthplace, political ideology, or other mutual affiliations, but their shared commitment to the immediate introduction of the Canadian tariff.

The battle lines were quickly drawn. The first issue of consequence in the new legislature was not the founding of responsible government, railway construction, or any other capital works of imperial concern, but tariffs.

Motions met with procedural wrangles by opposition forces, who were once again defeated. When the dust settled, members voted 14 to 9 in favour of the Canadian tariff. De Cosmos’ paper “regretted that all other interests in the province had become subservient to commerce” and ventured to predict that Canadian tariff proponents would “see their mistake by-and-bye, when too late to apply a remedy. . .there will be no drawing back, no help for it, however much we hereafter may have occasion to regret the suicidal policy we have pursued.”

The opposition lost the fight, and on March 14, 1872, the bill received its third and final reading, leaving only Royal Assent before the Canadian tariff system had full force.

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, anticipating a fait accompli, instructed: “The moment that your act passes adopting the Canadian Tariff, you should send a copy duly certified.” Yet the official consolidation of BC into the Canadian tariff structure did not end opposition debate.

The tariff issue helped give McCreight the premier’s post, but it also led to a rather tenuous hold on power, and ultimately to defeat. On December 19 1872, his government fell on an amendment to the throne speech, which said the administration of public affairs had “not been satisfactory to the people in general.”

The new premier-designate, Amor De Cosmos, now had the opportunity of building a more secure coalition – and the tariff issue remained in play. The new premier had to work with the same group of MLAs who had already largely committed to the Canadian tariff.

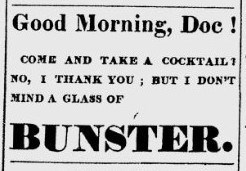

One of the first members to publicly switch sides was George Anthony Walkem (a future premier), who retained a cabinet portfolio in the De Cosmos government. As the new Attorney General, he advocated a “broader view” of the question than previously; one that afforded “a fair protection for farm produce” as economic conditions for the farmer had worsened. Arthur Bunster, MLA and brewery owner, confirmed:

The Canadian tariff had proved a curse to the country, inasmuch as its tendency was to drive people out of it. The general verdict after a year’s trial of the Canadian Tariff was, that they [the farmers] would gladly sell at cost and leave the Province. . . Was it not a shame and a disgrace to see Chicago bacon sent away into our mines and under selling Provincial bacon? Was it not a shame to see California flour sold less in this market than Provincial flour was sold?

Evidently, many felt it was a disgrace that home production was being severely undercut. In a committee of the whole on January 27, 1873, MLAs resolved to pursue the preparation of a petition that outlined specific changes to federal customs duties. This report was confirmed by a majority of one vote (12 to 11) and represented a complete change in philosophy and direction for the House. Yet before they could applaud their victory, Committee Chairman Joseph Hunter added his vote against the report, thus effecting a tie (12 to 12).

With full membership in attendance, the legislature was now more evenly divided than on any previous issue.

Parliamentary procedure required that the legislative impasse be broken in the house; the Speaker, James Trimble of Victoria City, readily agreed. In casting his deciding vote, Trimble attempted to end any future doubt that the province lacked legal jurisdiction on tariffs.

By his vote alone, the report was not accepted.

By this time, De Cosmos had left for Ottawa, resigned to working within the federal realm for changes to the Canadian tariff. Back home, Arthur Bunster continued to promote a made-in-B.C. scheme. Under Bunster’s instigation, the B.C. House was again prepared to re-examine the question in committee of the whole, but no report was forthcoming during the remainder of the De Cosmos government’s time in office.

With the collapse of the Conservative government in Ottawa over the “Pacific Scandal,” the tariff debate soon entered the field of federal politics. In January 1874 at public meetings in Saanich, all contenders for the federal riding of Vancouver [Island] District pledged their support for a modified tariff. In provincial byelections held at the same time in Victoria District (created by the departure of Arthur Bunster and Amor De Cosmos, who both sought federal office) farmers convened at the Prairie Inn and unanimously endorsed a pledge that demanded each candidate’s support for modified tariffs.

The declaration read: “I sincerely declare that I will not support or accept office from the present or any government until they shall have first introduced some policy or measure calculated to insure such a modification of the Tariff as will afford real and substantial protection to farmers.”

Needless to say, all candidates endorsed this resolution. Provincially, the Canadian tariff was still the main issue of contention in 1874. Federally, new Member of Parliament Arthur Bunster also continued the fight. In response to Liberal MP Edward Blake’s insensitive, indeed acid, assertion that British Columbia was “an inhospitable country, a sea of sterile mountains,” Bunster, before assembled MPs in the House of Commons, hauled a sack of homegrown, prize-winning Saanich wheat from under his Commons desk, “took a handful out of it and indignantly tossed it toward the member for South Bruce [Blake] as the best answer to his statement.”

For Bunster, such efforts were in vain. After having warned the province and the dominion for so many years that inadequate protection would drive people out of BC, in 1883 Bunster ultimately vacated to Oakland, California, where he continued to brew ales, as he had done in Victoria.

In hindsight it seems so obvious. We know that tariffs were important in any discussion of post-Confederation Canada, and certainly for the Prairies. So why, has the introduction of the Canadian tariff in British Columbia and its harmful effects received so little attention from historians? Large portions of early B.C. society were clearly dissatisfied, and this feeling manifested itself in the Legislative Assembly.

While historians have focused mainly on Canada’s promised railway, during the formative years of the province, politics was a political war over the introduction of the Canadian trade scheme. The fight over Canada’s default on building the transcontinental railway would soon follow!

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.