Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro recently accused the United States of plotting a coup against him. Regardless of how accurate or justified that may be, this has led some pundits to openly wonder whether the Monroe Doctrine is about to be dusted off.

What is the Monroe Doctrine? During the 19th century, President James Monroe asserted a U. S. protectorate over the entire western hemisphere. This policy declared that any involvement of European nations in North, Central, and South American countries would be viewed as "the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States."

Subsequent presidents such as Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan have maintained this position, and their perceived right to be involved in the affairs of their “backyard.”

Latin American countries were not the only ones potentially affected by the United States’ Imperial gaze. In fact, during the mid-19th century, both British Columbia and Nicaragua became preoccupied with the threat of potential annexation as encouraged by two American agitators with a shared history of urging United States expansion.

Those two agitators had another, very different, shared history – for a time, they were co-editors of the San Francisco Herald newspaper.

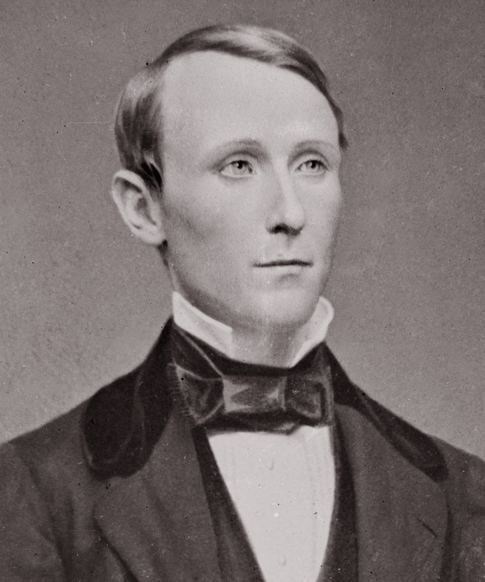

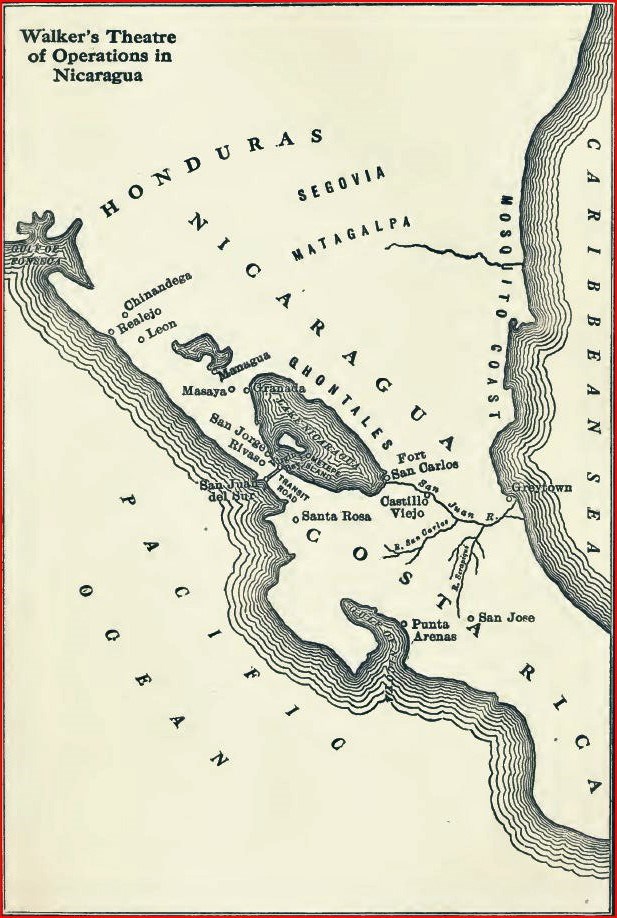

They were John Nugent, and General William Walker, the notorious filibusterer who led militias in the takeover of Nicaragua. During the 1858 Gold Rush, President James Buchanan appointed Nugent as Special U.S. Agent to the Fraser River to assert and protect American interests.

Nugent's appointment was feared by many as indicative of possible American intentions to annex British Columbia; especially so, when he invoked the United States' Nicaragua Policy with regard to “protecting” American citizens in B.C.

Nugent argued that Americans had been denied proper justice, and that the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) had been supplying their Indigenous allies with weapons to protect against the incursion of American gold seekers.

The close association of the HBC with their longstanding Indigenous trade allies was always suspect in the eyes of many Americans steeped in the notions of Manifest Destiny.

Nugent’s unpublished orders from U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass expressed great interest in the gold deposits of the Fraser River. The feeling in California was “that Uncle Sam sadly blundered when he yielded Lewis Cass’ ultimatum of ‘54° 40'’.”

Cass, who had urged the annexation of Texas and the whole of the Oregon Territory, as well as the occupation of Mexico, advised Nugent accordingly:

“the President desires to be accurately informed with respect both to the locality and extent of these discoveries, the mode in which they are improved…the quality of the gold discovered…means of access to the gold region…and generally all information on that subject of a reliable character.”

Nugent’s appointment was greeted by the San Francisco Bulletin with total disdain. “That he will permit the occasion of his official career to pass without getting Brother Jonathan into a collision with John Bull, is hardly possible.”

“Americans and Englishmen cannot mix,” asserted a letter writer to the Bulletin, “and but little will be needed there on Frazer river to provoke a crisis – a sort of independent California fight which will involve the two nations, even if the British cruisers on the other side do not.”

With the discovery of Fraser River gold, friction between British and American navy ships commenced off the coasts of Cuba, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama.

In the summer and fall of 1858, the British Navy had taken upon itself to haul over U.S. vessels, searching them for both slaves (having outlawed slavery) and American filibusters.

American officials were incensed with what they regarded as the high-handed practices of the British government to patrol the American hemisphere to prohibit the trade in slaves.

One agitated American looked forward to the day when miners bound for the Fraser River “might become the conquerors of Vancouver Island,” believing that his fellow citizens would “thunder a welcome to the new State of Vancouver.”

If anything, the British naval decision to conduct a right of search aboard American vessels served to fuel the filibustering mood among American communities along the Pacific Slope. An even greater provocation came later, with British plans to support the Nicaraguan and Costa Rican governments against the filibustering raids of General William Walker.

Though Britain was about to relinquish its territorial claim to the Moskito Protectorate, their departure was forestalled by the discovery of gold on the Fraser River. The Central American routes gained more importance to British interests with the creation of the Crown Colony of British Columbia.

As the American minister to Britain, G.M. Dallas, hypothesized to Lewis Cass, “the discovery of the golden sands in Frazer River, leading to the creation of the new colony of British Columbia, has increased the solicitude of Isthmian routes of transit.”

With the goldfields of the Fraser River seemingly offering untold riches beyond those of California, British interests required a strong presence in Central America. With the appointment of John Nugent, the actions of the Royal Navy off Nicaragua sent a strong message: regardless of the self-serving pretensions of the Monroe Doctrine, whether in Nicaragua or potentially in British Columbia, filibustering would be met with strong opposition.

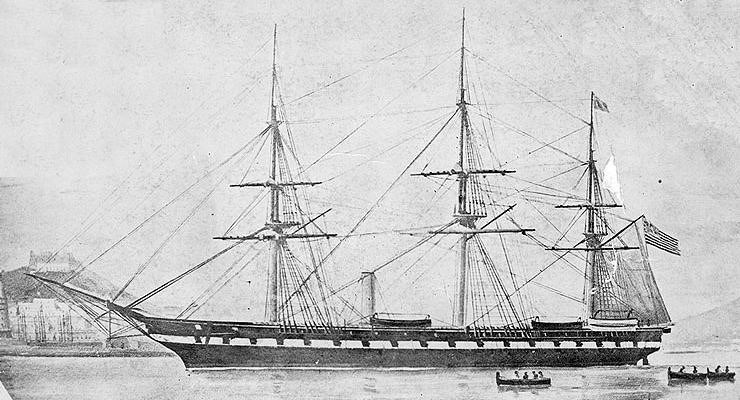

James McIntosh, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Home Squadron, felt the inspection of his ships by a foreign power was an invasion of national sovereignty.

Writing aboard the flagship USS Roanoke off the coast of San Juan del Norte, McIntosh informed the Secretary of the U.S. Navy, Isaac Toucey:

“It looks like a renewal of the scenes which lately occurred around the Island of Cuba, changed only to filibusters for Africans. You may rely on my taking prompt and efficient measures to protect the honor of our flag should it become necessary; and, if really her Britannic Majesty’s officers have instructions to board and examine American merchant ships for filibusters, under the very guns of the ships of my squadron, the time must be very short before the most serious consequences may be anticipated.”

McIntosh was of the opinion that the British Navy had abrogated the terms of the Clayton-Bulwer Convention, agreed to by both countries, which stipulated that “neither will ever erect or maintain any fortifications commanding the same, or in the vicinity thereof, or occupy, or fortify, or colonize, or assume or exercise any Dominion over Nicaragua, Costa Rica, the Mosquito [Moskito] Coast, or any part of Central America.”

Yet, the American commander was to have a frank discussion with a British officer who “distinctly declared that England had never abandoned the protectorate.”

Fraser River gold had undoubtedly delayed Britain’s departure.

General M.M. McCarver, a member of the California legislature, gave as his considered opinion that the discovery of gold on the Fraser River “on the line which divides the territory of two of the most powerful nations on earth…may be the means of producing blood as well as gold.”

There were reports as far away as England that Walker himself might have “possible intentions in British Columbia on the part of the Americans – with or without direct support from their Gov’t.”

As it was, the determined stance of the Royal Navy off the coasts of both B.C. and Nicaragua thwarted American ambitions. With Cass’ Nicaraguan directive being applied to the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, little wonder that Britain reinforced its presence in Central America.

Luckily for Governor James Douglas, Nugent determined that the richness and extent of British Columbia gold was limited, and did not warrant the continued influx of American miners. Had it been otherwise, American policy may have favoured annexation.

Nugent concluded:

The Americans, it is true, were in sufficient force any time within the first six months to make successful any movement on their part towards the seizure of the colonies. . . It is true that, in all probability, both will eventually cease to be under European control.

Their ultimate accession to the American possessions on the Pacific coast is scarcely problematical – but in the meantime their intrinsic value either of locality, soil, climate, or productions, does not warrant any effort on the part of the American government or the American people towards their immediate acquisition.

British Columbia escaped a possible American takeover, but 160 years later, the Monroe Doctrine still hasn’t entirely disappeared into history.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.