Whenever I travel up the No. 1 Highway through the Fraser and Thompson corridor, I continue to be amazed about the impact the gold rush had on Indigenous communities, and how so much has been forgotten about Washington State’s involvement in the early development of the province.

Traveling by such lesser-known places as the Chapman’s Bar, Boothroyd, and Cook’s Ferry Indian reserves has often led me to wonder who were the namesakes of these Indigenous lands and why do we know so little about them?

I decided to try and find out.

In my view, the historical exploration of transboundary regions, such as the Pacific Northwest (or dare I say, Canada’s Southwest!), have been largely undermined by preoccupations with nation-building history in two separate countries that has encouraged the blinding influence of a political divide.

Cross-border migrations across the 49th parallel were nothing new for Indigenous peoples, fur traders, gold seekers or indeed my own grandfather who, during the late 1920s, drove from B.C. to Mexico on two separate occasions – once in a 1928 McLaughlin-Buick motorcar!

B.C. was part of a natural North-South world – the Pacific Slope – where previously the Spanish, Russians, British, and Indigenous nations once moved quite freely west of the Rockies – until the United States and Canada commenced their new nation-building narratives to encompass their recently-claimed portions of the Pacific Coast.

These East-West reconfigurations had little interest in telling stories of the previously natural North-South flow, and the transcontinental nationalism of the U.S. and Canada effectively severed Pacific Slope communities from a shared history now largely forgotten.

Canadian historians often fail to recognize the Pacific province does not fit any simple Laurentian thesis, whereby Canada’s gradual westward expansion was based upon the commercial fur trade and economic system of the St. Lawrence region.

One of the goals of Confederation was to reorient these connections into an East-West alignment, but it was not always so.

In 1858, Britain countered Governor James Douglas that it was not the policy of Her Majesty’s government “to exclude Americans and other foreigners from the goldfields."

“On the contrary,” cautioned the Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, “you are distinctly instructed to oppose no obstacle whatever.”

Soon tens of thousands of American miners moved north across the still-unmarked international divide; many believed the new goldfields were actually in American territory.

Gold seekers from Washington Territory were some of the very first to arrive.

One such person was Captain George Wesley Beam, later a member of the Washington Territorial Legislature, who wrote in his diary (just south of Yale, BC) that “The [Fraser] river bears south much more than you have an idea.”

Other residents from south of the border – such as William Chapman, George Washington Boothroyd, and Mortimer Cook – would have agreed.

During the transformative year of 1858, there was literally no parallel marked out on the ground to separate British Columbia from Washington. The 49th parallel was of little consequence; many Americans either hoped or assumed the U.S. Boundary Commission would establish the goldfields south of the international divide.

Until the boundary was located and confirmed, many American gold seekers left their mark in the form of place names in the goldfields.

John Chapman, for instance, the founder of Steilacoom City in Washington Territory in the early 1850s, was the undoubted namesake of Chapman’s Bar (near Alexandra Lodge) in the Fraser Canyon, the name later used by colonial surveyors in defining the Chapman’s Bar Indian Reserve.

Likewise, George Washington Boothroyd, a member of Major Mortimer Robertson’s 1858 “Yakima Expedition” to the Fraser Mines, traveled through the American and Canadian Okanagan region as part of a large-scale militia determined to fight Indigenous peoples in their bid for gold, later building his roadhouse at what became known as Boothroyd’s, near today’s Boothroyd Indian Reserve.

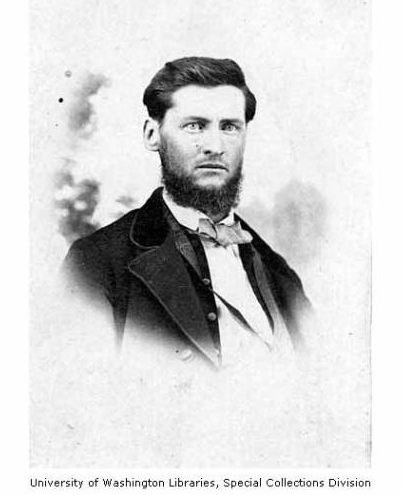

But it was American Mortimer Cook who perhaps provides the best example of this forgotten history between B.C. and Washington State.

Like many other gold seekers to B.C., Cook had previously fought in the American war with Mexico before traveling to the California gold rush in 1849, where he partnered with John Warner. These two subsequently heeded the call of the Fraser River gold excitement.

By 1861, Cook and Warner built one of the first crossings of the Thompson River at today’s Spences Bridge – named after Thomas Spence, also a veteran of a filibustering raid into Mexico.

During the time of the “Cook’s Ferry” community, Warner apparently married “Ellen Thompson”, a member of the Cook's Ferry band of the Nlaka’pamux nation, and as the online Skagit Valley Journal notes, “she was rumored to be the daughter or sister of the chief of the tribe.”

On this side of the 49th parallel, the name of Mortimer Cook is known for this one particular achievement – but it was certainly news to me to discover more from sources south of the border.

Ten years after the establishment of Cook's Ferry, he went on to construct another ferry – and then toll bridge – near Topeka, Kansas. This was apparently the first iron bridge erected in the region. From there, Cook established one of the first gold banks in Santa Barbara, California, becoming mayor on two separate occasions in the 1870s.

By this time, Cook had amassed significant wealth, but quickly lost his banking fortune about 1878, and this compelled him to ultimately return to Washington State where he next founded the old town and logging community of Sedro, or today’s Sedro-Woolley.

How do we in British Columbia know nothing about Cook’s later accomplishments, or the fact that he was responsible for founding two different communities on either side of the border?

In all the years I have listened to American public radio based out of Sedro-Woolley, neither did I imagine that there was such a link to this side of the border, nor to today’s Cook’s Ferry Indian Band.

During those early years, the 49th parallel wasn’t much of a dividing line, but national myths on both sides ignore these early linkages. Put quite simply, these North-South connections didn’t fit the new Canadian national narrative.

We can’t just blame Ottawa. More often than not, historians of British Columbia have denied the American presence as having effectively shaped our social, political and economic life.

It seems to me that the North-South orientation of B.C. was part of a larger Pacific Slope puzzle, a piece that has never properly fit the stories we tell ourselves.

In the meantime, I suspect there’s yet more historical evidence waiting to be found south of the border to explain these seemingly anomalous place names in British Columbia.

Must be time for another road trip.

A fifth-generation British Columbian, Daniel Marshall is an author, professor, curator, documentarian, and researcher focusing on British Columbia’s relatively untold but rich history. He is a recognized leader and award-winning researcher on historic Native-Newcomer relations, and their evolution and implications on Aboriginal rights today.

His award-winning documentary, Canyon War: The Untold Story, has aired on Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS. His latest book, Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado, is available in bookstores across B.C.