When the results are in, the big story of the election will be what you think: is the next prime minister Justin Trudeau, or Erin O’Toole?

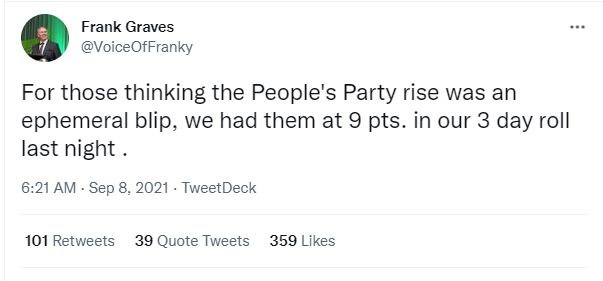

But if current (and VERY recent) polling trends hold, the other story looks like Canada will be forced to reckon with the People’s Party.

Before we go any further, a big asterisk: the word “if” does a lot of work here.

That’s not to cast aspersions on the polls or polling firms. But people honestly telling a pollster they support Party X doesn’t always mean an eventual vote for Party X.

BC has some applicable experience here. The provincial Conservative Party routinely polls much higher than it actually performs on the ballot.

The reasons are still debated, and several are unique to BC’s peculiar particular political landscape. But generally speaking, when a party is perceived to have a low chance of winning, its supporters often vote for their own personal next best – or least worst – option. That’s assuming they even have a candidate on their local ballot, although the PPC is running close to a full slate, with candidates in 312 out of 338 ridings. (The Greens have 252.) Perhaps most often, they don’t vote at all.

But if the PPC does garner anywhere near as many votes as recent polls indicate, many of which have them at 10%, we’ll have quite a lot of thinking to do.

One EKOS poll had 21% of voters aged 18-34 intending to vote PPC, within one and two points of the NDP and Liberals, respectively. A 10% overall vote share would be a quantum leap in just two years – quite literally an order of magnitude higher than the 2019 election.

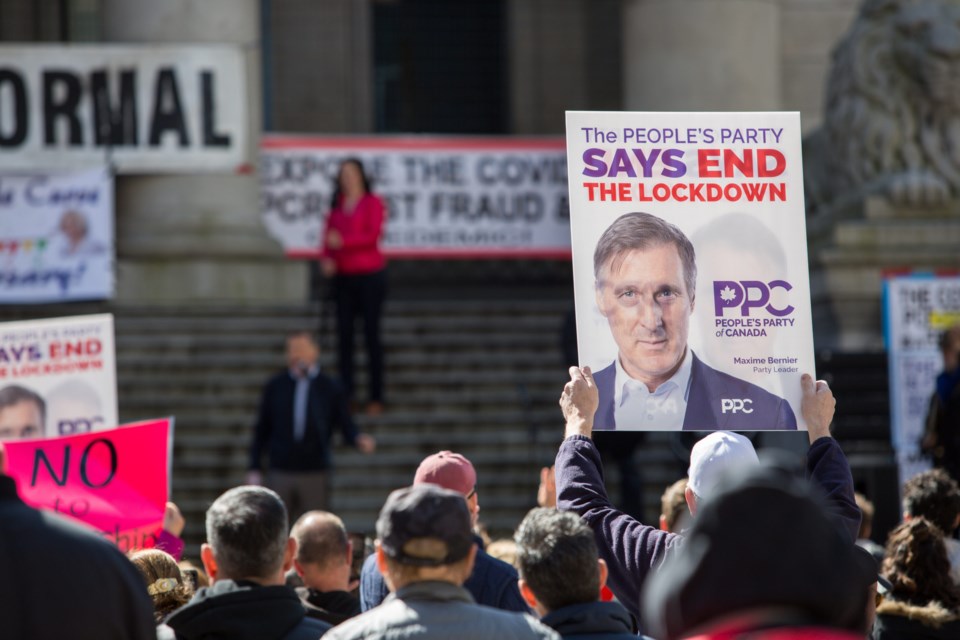

What’s changed since then? Well, for starters, a global pandemic. It’s not a coincidence the PPC has presented itself as opposed to all the necessary restrictions that frustrate many people’s day-to-day life – including the lack of a day-to-day life.

In other words, there’s a chance the PPC is a temporary clearinghouse of pent-up pandemic frustration, and not a long-term political movement. There’s every hope that once the pandemic ebbs, the PPC’s support will prove delible.

This rosy view ignores the rise of populist parties across Europe and the Americas. What’s driving this global trend is beyond the scope of this column, but a PPC surge would be fairly conclusive proof that Canada is not immune.

Even if the polls hold true and the People’s Party wins 10% of the national vote, that likely doesn’t translate into a seat. Unlike the Greens, their support doesn’t appear to be saturated enough in any one region to win a seat. (Again, the word “appear” does a lot of work there.) But even if no PPC candidates win, 10% of the vote almost certainly legitimizes them enough to be included in things like leaders’ debates.

Interestingly, the People’s Party picking up 10%, but still denied a seat under First Past the Post would spice up and complicate future arguments for electoral reform. All too often, these have been positioned explicitly as a way to help left-of-centre parties like the NDP or Greens, and concerns any other party could take advantage were waved away as fear-mongering.

If the PPC not only outperforms but doubles or even triples the Greens, that argument – like many other assumptions about Canada – will need to be put to bed.

Maclean Kay is Editor-in-Chief of The Orca

SWIM ON:

- Maclean Kay last wrote about Hannah Hodson, who's looking to climb two mountains: become Parliament’s first openly transgender MP, and win Victoria for the Conservative Party.

- Almost two whole years ago, Michael Taube took lessons from the 2019 federal election.

- Jody Vance: If we’re going to put COVID behind us, we need to set assumptions aside, and help the vaccine hesitant get past their particular barrier. This is one story.