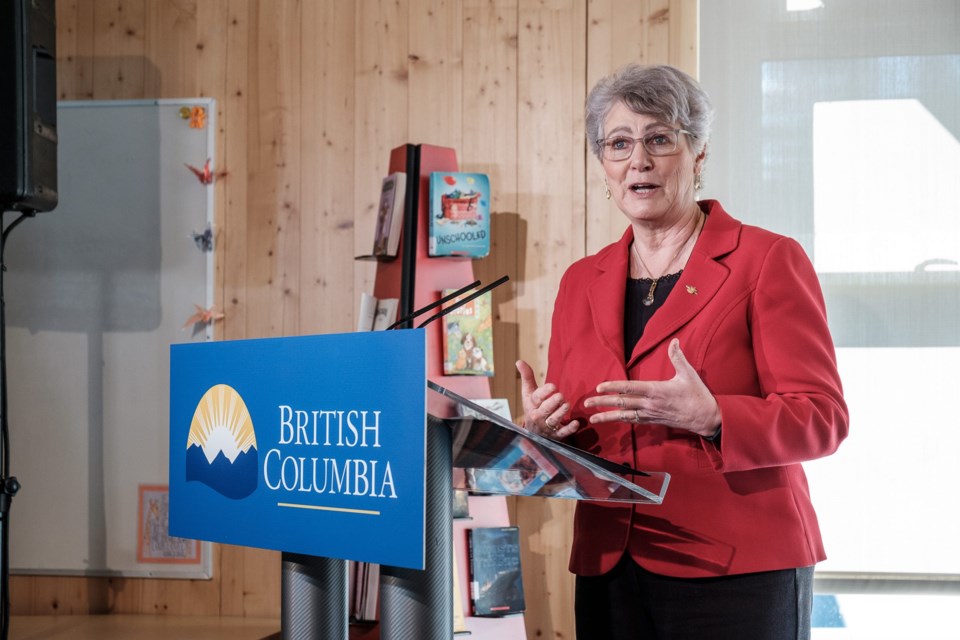

Like many women in politics, BC’s forests minister Katrine Conroy has probably experienced more than her fair share of online abuse. In fact – the phrase “her fair share” is a misnomer; there’s no such thing as a “fair” share of abuse.

The amount of abuse women politicians endure on an everyday basis is horrible, well-established, and knows no partisan divides. And while there’s always a baseline of day-to-day swill, abuse increases the more officials are in the news, and if they’re involved with a contentious issue. Whatever your position on the Fairy Creek logging and protests, it definitely qualifies.

Given all this, it was no surprise to learn Conroy recently set her Twitter account to “private” – meaning only her followers can view her tweets, and she can approve or reject new follower requests.

As this Twitter user puts it (Okay, he’s also the BC Green Party’s Communications Director, but he raises an interesting point)...should this be allowed?

The answer is complex – and in my opinion, heading the wrong way.

The question of whether politicians can block people on Twitter reached its ne plus ultra, as so many issues did, under former US President Donald Trump. An appeals court ruled he couldn’t block people on Twitter, saying it was a “public forum” where people have a right to be heard. Ironically, he was later bounced by that same public forum.

There’s a Canadian legal precedent, as well. Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson was sued by some Twitter users whom he had blocked on the platform – and settled, agreeing that his account was a public forum.

Watson is by no means alone. It’s not hard to find other efforts to shame politicians (especially female politicians) who block users. Here’s one article about Conservative MP Michelle Rempel Garner that also explores this issue.

You can see how some might arrive at this conclusion. After all, the bio on Conroy’s account is her MLA and ministerial title, and nothing else.

So there’s precedent – but that doesn’t mean this is the right thing to do.

Consider: if the social media accounts of public officials must be kept open as a public forum, the obvious implication is that public officials then must have and operate social media accounts. If you can’t close a public forum, you can’t refuse to build one.

In other words, if Katrine Conroy – or Sonia Furstenau, or Shirley Bond, or whoever – didn’t have a Twitter account, she’d have to start one. Either when first elected, or appointed to cabinet. (Who knows where the line should be drawn? Crown corporation directors? City councillors? School board trustees?)

And given that we’ve already established women in politics experience substantially more social media abuse – beyond any question at this point – if they are not allowed to block or make their accounts private…what are we condemning them to?

There must be a better way. Luckily, there is.

Barack Obama established official accounts for president, first lady, vice president, and press secretary (@POTUS, @FLOTUS, @WhiteHouse, @VP and @PressSec, respectively), which are inherited by whomever holds the office, and doesn’t come with them when they leave. So for example, today Joe Biden (or his staff) operates @POTUS, as did Obama and Trump.

It was a good idea. The problem was the first person to inherit it – Trump – simply refused to use it, opting instead to keep using his own personal account. That’s where it got murky; it was this account the court ruled was a public forum.

But Trump is an extreme case. Just because he made a mess, it doesn’t mean Obama’s idea isn’t worth trying here. Institutional accounts might clarify some of the blurred personal/political/professional lines that people in government live with.

It would be easy to establish accounts like @BCPremier or @BCForestryMinister for their current holders, eventually to be passed onto their respective successors. Yes, it would be novel seeing John Horgan’s tweets underneath whoever takes over – especially if they’re from a different party – but the public forum is about the office, not the individual filling it. And even today, if you search the provincial government’s well-maintained Flickr account, it’s easy to find photos of then-Premier Christy Clark and even Gordon Campbell. Why should social media be any different?

It might also lower the political temperature for some ministers – if (for example) David Eby’s Twitter account is to be considered a public forum as the impartial Attorney-General, partisan comments might seem out of place. Why not continue to use his personal account for those, and keep the official stuff on something like @BCAttorneyGeneral?

No question, it’s unfortunate Conroy felt she needed to make her account private. All things being equal, it’d be better if it wasn’t. But there’s no shortage of other ways to reach her and/or her ministry. And even if a court theoretically compelled her to make her tweets public, there’s zero guarantee your questions and criticisms – even the perfectly valid ones – would ever be seen. It’s much more likely accounts like Conroy’s would lay dormant, or turn into a “broadcast account,” where the user sends tweets but never even looks at the mentions.

Is that better? If your answer is yes, who is it better for?

It’s hard enough to get talented young people – and especially young women – to enter the fray of public service. Telling them they have literally no choice but to sift through heaps of vile social media abuse won’t help.

Maclean Kay is Editor-in-Chief of The Orca

SWIM ON:

- Maclean Kay last wrote about the pros and cons - as he sees them - of Kevin Falcon's proposal to change the name of the BC Liberal Party.

- Maclean Kay has written about how politics treats women horribly before.

- The Orca is proud to publish a podcast series exclusively about - and for, and by - women in politics, Ellected. In the very first episode, Sarah Elder-Chamanara welcomed new Green Party of Canada leader Annamie Paul.