After a particularly raucous Question Period – where it was impossible to actually hear questions and answers – one could be forgiven for asking…why?

“It’s one of the least desirable aspects of our democracy,” said Saanich North and the Islands MLA Adam Olsen, one of three Green members of the legislature. “It leaves an impression on people who visit – and that impression is not a good one.”

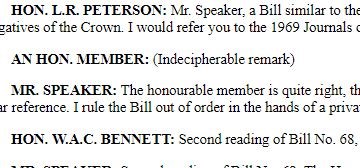

INTERJECTIONS

Heckling has a well-documented history, going back long before arguably the most infamous Canadian heckle, which Pierre Trudeau insisted was just “fuddle duddle.” (His target maintained that the prime minister actually said something that rhymed with “truck through.”)

It gives me enormous pride to report “heckle” is originally a Scottish word (of course it’s a Scottish word), defined in 1808 as a verb meaning “to tease with questions or examine severely.”

It quickly came to be most often applied to questioning parliamentary candidates, and then, parliamentarians, whose benches were placed two sword lengths apart – just in case the words became actions.

The practice came to Canada, with media reports of Parliament shortly after Confederation describing members acting “somewhat in the manner of irrepressible school boys on the absence of the teacher,” up to and including making meowing noises and even setting off firecrackers – all in the name of distracting the person speaking.

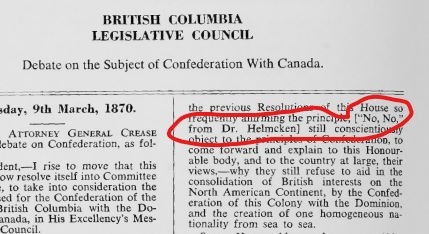

In B.C., there are recorded heckles in the debates about entering Confederation (some from Amor de Cosmos, no less) and on the very first day of Hansard, in 1970. Some are specifically transcribed, but over the years, the vast majority are simply noted in the record as “Interjections.”

While meowing – and setting off firecrackers – is obviously going too far, the basic purpose of heckling hasn’t changed since the early 1800s: to “examine severely” the government.

“It’s literally our job to test, challenge, and prod them on what they’re saying,” says Opposition house leader Mary Polak.

“The whole point is to communicate something to the public. From time to time, a well-placed heckle can draw the point you’re trying to make about the other side’s position.”

“If you want to point out a flaw in what (the other side) is saying, a well-placed heckle can do that,” says Polak.

Okay, so heckling has a long history. Does it still have a place?

“QP is our outlet. That’s where the emotion and raw feeling is supposed to get out,” says Polak, “so we have nice peaceful streets when we change government.”

Olsen agrees.

“QP is a bit of theatre, and a pressure release valve – and it’s also the most public. It’s that 30 minutes when we’re all in the House together.”

A former cabinet minister and current Official Opposition House Leader, Polak has seen it from both sides.

Olsen says he “gets dragged into it every now and again – but I come from sports, I’ll chirp every so often.”

You only need to sit in the legislature once to hear one or two quality zingers – but heckling sometimes creates something of a feedback loop, getting louder and louder into a cacophony of shoutiness.

“I’ve done my best not to be ‘shouty and loud,’ but it is the nature of the place,” says Premier John Horgan, whose booming voice and quick wit made him an effective – and frequent – heckler in opposition.

“Oftentimes, when their voices go up, the heckling goes higher. This is kind of the nature of the place, when someone is yelling at you, you end up having to yell back to be heard. I prefer not to do that.”

Like anything else, it can quickly become too much of a good thing.

“Sometimes it gets to the point where there’s too much noise, you can’t hear the person speaking,” says Polak.

The shouting can sometimes be counterproductive – for two reasons.

First, Question Period is 30 minutes long – no more; no less. And unlike injury time in soccer, when the Speaker stops proceedings to calm things down, the clock keeps ticking.

“It’s valuable time, and when the Speaker has to stop us, that’s our time,” says Polak.

Second, if only one side is heckling, it looks bad.

“You will notice we have quite consciously reduced amount of heckling and noise,” says Polak. “It’s a conscious decision (leader) Andrew Wilkinson led us to.”

“When you then look at what that looks like, quiet and professional, and the government answer in contrast is yelling – it looks really good.”

KEEP IT PROPORTIONAL

The million-dollar question is: would heckling increase or decrease under proportional representation?

“I would hope it would [decrease],” said Horgan, adding that he hopes shouting to make yourself heard “won’t be as apparent” under PR.

Polak disagrees.

“If you’re going to have debate, you’re going to have heckling – and I would argue you’d see more heckling. In order to form a government, you’d have parties who agree to form together – then small parties wanting to get attention.”

“I don’t see how that argues for less yelling.”

Olsen says whatever system B.C. has, the volume and intensity of heckling may come down to math. With such a precarious majority, all members of the house are on edge – a situation that can just as easily occur again Proportional Representation.

“We’re on a knife’s edge right now. We might be on a knife’s edge in the future.”

Better a knife’s edge than a sword in anger.

Maclean Kay is Editor-in-Chief of The Orca