A few weeks back I was visiting my hometown of Kelowna, family, and the gravesite of my paternal grandparents. I was also there to see the granite marker our family recently ordered for my late father.

I was visiting just as the re-discovery of 215 graves at the Kamloops “Indian” residential school was hitting the headlines. Concurrently, various governments announced funding to explore and (I assume) restore markers to graves now unmarked where records can be found.

As I wandered around the cemetery, I was struck by the contrasts —the memories available due to gravestones and markers, in distinct contrast to the absence of the same at the Kamloops residential school for children and whomever else turns out to have been buried there, as well as at other similar graveyards across Canada.

I’ll offer some thoughts on why tax dollars spent to erect markers and gravestones as such former residential schools is a worthwhile and positive use of public funds, and also why this issue also needs more nuance, but first, consider how such markers and gravestones can make us more curious about history and others.

Public and private memories

I also have an aunt buried at the Kelowna cemetery, and another marker was recently placed near my grandparents for an uncle who passed away 41 years ago but who was buried in Ontario. As I remembered my dad, grandparents, an uncle, and an aunt, I also noticed the graves of a pastor and his wife from a church I attended in Kelowna as a kid. The ashes of my brother-in-law’s father, who passed away just last year, are also stored there. There were memories in abundance about all of them as I quietly pondered their lives in the early morning heat.

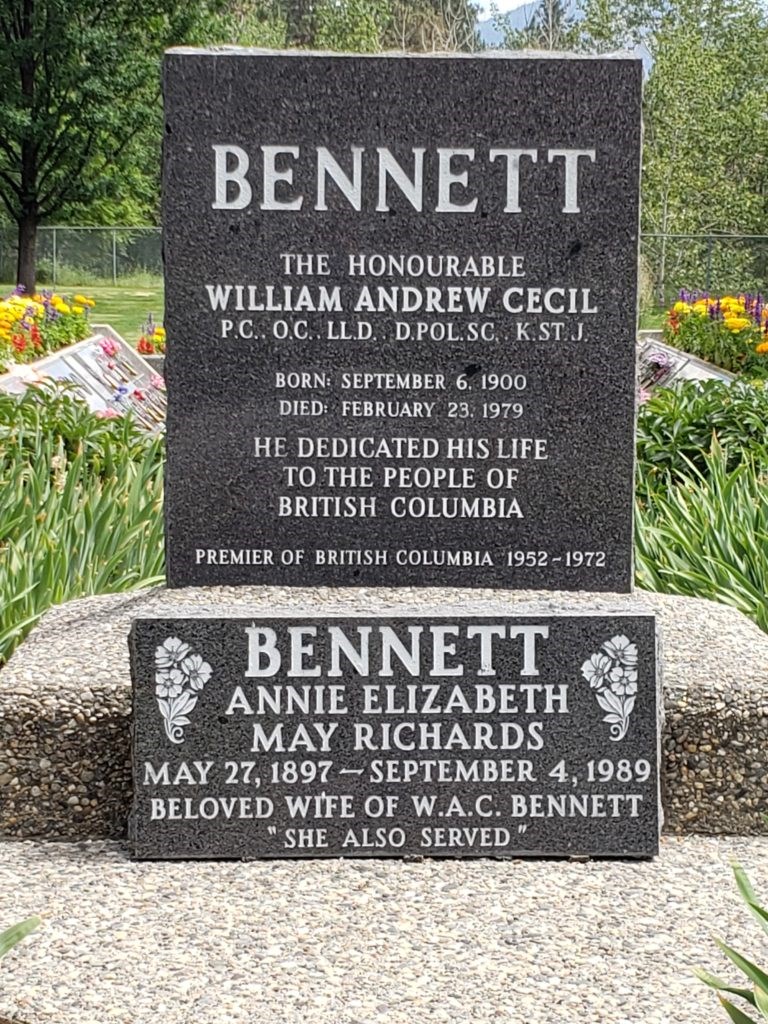

Sometimes, the public and personal memories can mix. Back when I was in school, there was a tradition for decades where graduates of Kelowna Secondary School were invited to gather for a lawn party at the then-home of May Bennett not far from our high school. (May Bennett was the wife of the late premier, W.A.C Bennett, who passed away in 1979.), I graduated in 1985, when May Bennett was still alive, and our large graduating class continued the tradition. We never met Mrs. Bennett but all appreciated the gesture.

At the same cemetery where members of my family are buried or memorialized, W.A.C. Bennett, his wife, May, and Bill Bennett, are all buried. Together, those two premiers represent 31 years’ worth of premiership in British Columbia. History is brought alive even by tombstones.

Our shared histories and curiosity

That day at the cemetery also provided another contrast and more thoughts on remembrance. I spent time looking at the markers and gravestones from some of Kelowna’ earliest years as a town, i.e., the late 19th and early 20th century, and especially the graves of those of Japanese and Chinese descent.

I have a natural interest in early immigrants from Japan; I taught there for two years. I have an abiding curiosity about and appreciation for the country, culture, and people. When I saw the markers and gravestones of those of Japanese descent, it piqued my interest. I spent an hour wandering and wondering about those who contributed to Kelowna’s early years, what their life 50 years ago or 100 years ago or more might have been like.

The earliest tombstone I could find for someone of Japanese descent was for Shojiro Kimura, born in 1869 and who died in 1949. There was no indication when he came to Kelowna. It is possible, perhaps even likely, given the internment of Japanese in the Second World War, that the interior only became home for Kimura after being forcibly relocated from the coast, as most those of Japanese descent were.

It is not clear when the first Japanese arrivals came to Kelowna, but there were markers of an early 20th century presence. Here, the tombstones can also punctuate tragedies.

Several markers were about infants whose existence in our world was brief: Masuharu Terai breathed for just one day, in 1933; a sibling, Joji Terai, also matched only that one-day mark, in 1934. Hanayo Ueda’s tombstone marks “Aged One Day,” and is from 1935. Another worn stone marks the short life of another infant, Chika Tamaki, with no year given but whose inscription reads “Aged 6 Months.”

Nearby, “Baby Fujimoto” is marked with the start year of 1920 and the end year is the same. The infant without a first name is beside another gravestone, Suetaro Fujimoto, who I assume must be the baby’s mother. Suetaro was born in 1893 and passed away at 26 years old, and in the year before her baby, in 1919. Death in childbirth was once common. I wonder if that fate befell Suetaro Fujimoto.

Slightly closer to our own era, Eugene Shioshaki perished as a five-year old, born in 1961 and lived until just 1966, one year before I was born. As a kid, I could enjoy Kelowna’s beaches, peaches, lake, and four seasons of scorching heat and damp winter snow. Eugene would have only experienced a sliver of that. There is sadness in that awareness.

Sometimes a Kelowna tombstone reminded me of my own time in Japan, if only because of recognizing the geography. Sadajiro Hidehira hailed from Fukuoka-ken, and died in Kelowna on July 30, 1917. A “ken” is akin to a Canadian province and Fukuoka was the next province over to where I lived in Japan. Fukuoka is also the name of that province’s largest city. I took in a ball game there once with tens of thousands of fans, perfectly synchronized whenever their team scored a run.

Kelowna also had an early Chinese presence. A memorial plaque at the cemetery notes Kelowna’s Chinatown began in 1892, a few decades after the first Chinese immigrants came to the west coast in search of gold in both California and British Columbia. Local historian Sharron Simpson, whose family dates back to early settlers, wrote a history of Kelowna in 2011. In it, Simpson mentions a Chinese cook who prepared meals in a “lean-to cookhouse” near to the Grand Pacific Hotel in the 1890s.

By 1909, 15% of Kelowna’s population was Chinese and two years later Sun Yat Sen would visit the town, which then numbered just 1,661 people. The earliest tombstone for someone of Chinese ancestry I could find was from Lee Toy, born in 1863 and who lived until 1945. There were no other details.

Imagine their world

Beyond those of Asian decent, early English settlers made up a large chunk of early Kelowna. Here too, markers, official memorials and tombstones can bring us into someone else’s world.

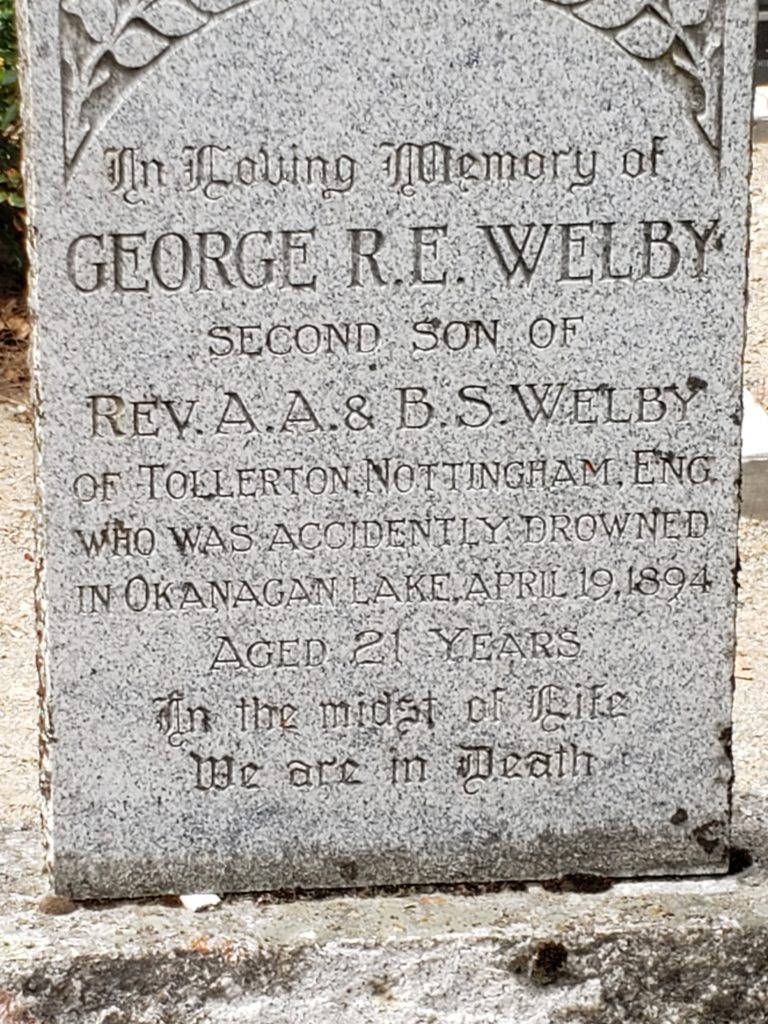

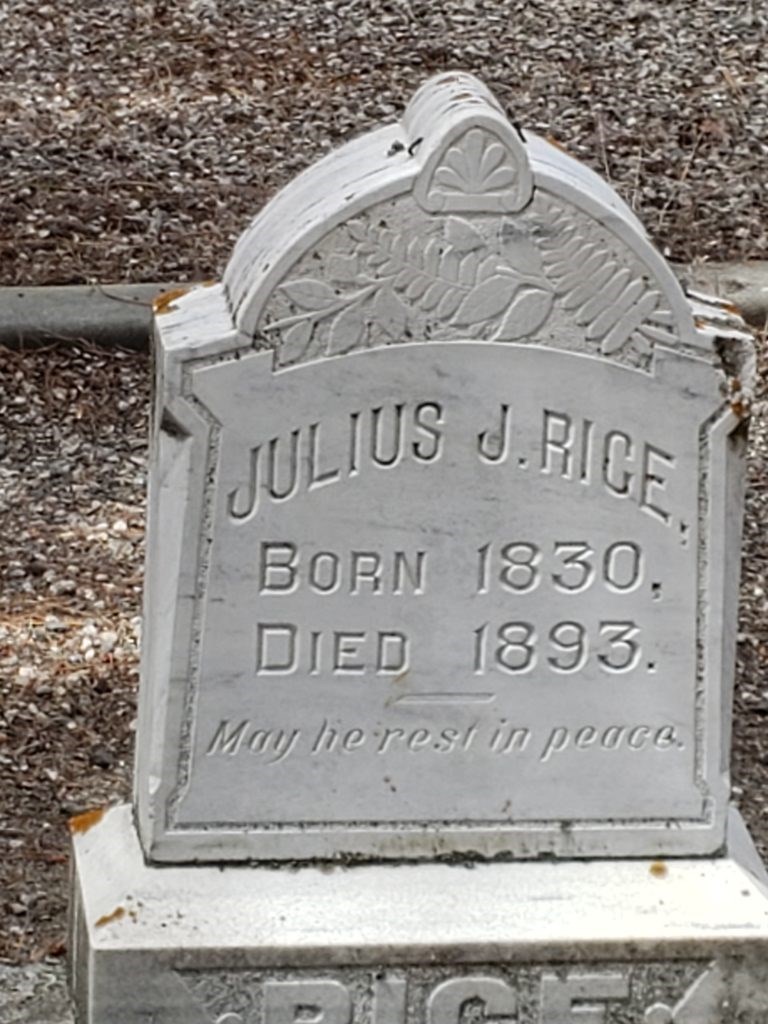

One public pioneer cemetery sign noted the first person to be buried in Kelowna Memorial Cemetery was Julius J. Rice “who died of starvation and exposure on his Black Mountain farm in 1893.” He was born in 1830. His tombstone notes both dates. The second person to be buried in that cemetery was George Welby, second son of Reverend A.A. and B.S. Welby, of Tollerton, Nottingham, England. George was 21 years old when he drowned in Okanagan Lake.

Both deaths are touchstones, albeit only now. My late father built a few houses on that mountain in the late 1970s. I swept out some sawdust from the framed structures not far from where Rice perished. More generally, in our youth, we carry out such tasks, run across fields, hike up mountains and swim lakes while crossing the paths of others’ tragedies without a scintilla of awareness. It is normal – you don’t know what you don’t know—but no less poignant for that.

Family love and religious traditions are evident as well in cemeteries. Yoshimatsu Naka was born in 1895, eight years before Henry Ford’s Model A automobile was first in production. He lived until 1982, one year after the first space shuttle launch and 13 years after the first moon landing. Yoshimatsu Naka is described by his family as a “loving father.”

Tamenori Kusumoto was born on August 12, 1918 and died on August 3, 1945. Given his age—just days shy of his 27th birthday, and the date of his death—just weeks before Japan surrendered, I wondered if he died in combat. He is described as “Asleep in Jesus.” Nearby, the family of Tatsujiro and Kayo Terada marked their years: 1892 to 1952 and 1897 to 1969 respectively. Their tombstone tells us their blissful “Peace in Nirvana.”

The importance of remembrance

Markers and tombstones naturally raise questions, pique our curiosity, and also can, if we are open, heighten our empathy for others, whether living or long-deceased. In the case of residential school graveyards, it does make sense for our tax dollars to now be spent to see if longer-lasting markers can now be placed on what is in essence rediscovered gravesites.

This is because, as per above, the deceased do deserve to have future generations wonder and wander just as I did about Eugene Shioshaki, Sadajiro Hidehira, and the many others buried on a mountainside overlooking Kelowna. Obviously, if records exist of who perished, marking individual gravesites would be a spur to just such musings about their lives including lives cut short.

Here, some nuance is needed. Some immediate media reporting wrongly referred to older gravesites as “mass graves” and also assumed no markers had ever been placed on individual graves. In calm opposition to such sensationalism, in Saskatchewan, the Cowessess First Nation chief remarked on graves near the Marieval Indian Residential School in existence from operated from 1899 to 1997: Chief Cadmus Delorme told reporters that “This is not a mass grave site,” but one with unmarked graves at present, also noting they previously might have been marked.

That initial reporting spurred my thoughts as I gazed at my own relatives’ memorial markers. Those are in granite, the same stone used to build the pyramids. The markings will one day fade with time, perhaps a century or two from now and then future generations will need to decide if they wish to restore such sites. Nonetheless, the possibility did occur to me that some nun or teacher in 1920 or 1950 might well have marked individual graves with a wooden marker, cross or tombstone. Those of course would not have survived the weathering of time.

In fact, a submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) noted just this practice, at least in part. In a 44-page submission, Prof. Scott Hamilton of Lakehead University showed great diligence, respect and empathy by detailing past practices, and offering some recommendations about how to address the “gaps in our current knowledge about school cemeteries, and how best to document, commemorate and protect them.”

He observed that “While some graves and cemeteries associated with the residential schools are known and are still maintained, others are now unknown or incompletely documented in the literature, and may even have passed from local memory.”

As far as how children and others (some gravesites also contain adults and were also community gravesites with non-Indigenous burials) were commemorated at the time, Hamilton notes that “Even when considering presently known and maintained cemeteries, some graves may lie unrecognized after the decay and disappearance of wood grave markers and enclosing graveyard fences,’ which he notes “presents a serious challenge for identifying, commemorating, or protecting unmarked graves and undocumented cemeteries.”

Given burial practices were ad hoc as Hamilton notes, and in some extreme cases such as the influenza pandemic that swept the world between 1918 and 1920 upended even standard burial practices, the Lakehead professor offers some useful recommendations to governments now on how to restore memories.

There is much detail in Hamilton’s submission and is worth reading in full. But in brief, options exist from heritage designations to other municipal, provincial and First Nations designations that would protect such sites. Identifications are a much more complex task, but local records will be of some assistance where they exist.

Memories will fade one day but in centuries

Back in 2008, I hiked through Scotland’s Isle of Skye with some friends and came across dilapidated graveyards that dated back to the 17th century. Of course, some graveyards in the United Kingdom and in Europe go back much farther than even that. One day, my families’ markers will fade, even those made of granite, and future generations in 2221 or 2321 may allow such memories to fade permanently in the mists of time.

But in the present, my buried relatives are near enough in time for memories to rise to the surface. On residential school graves, one need not accept errors in early reporting as definitive, but proper documentation and then commemoration is the right thing to do, including with taxpayer funds.

The children as children and others buried there, be it in 1890 or 1950, are yet near enough to all of us to accord them respect, remembrance, and to give everyone the chance to wander and wonder.

Mark Milke wears many hats and one is that of an author. His most recent book is The Victim Cult: How the culture of blame hurts everyone and wrecks civilizations.

SWIM ON:

- Mark Milke last wrote about things to read. On the beach, this summer.

- After the first discovery of unmarked graves in Kamloops, Ada Slivinski made the case for a national day of pause and reflection.

- Rudy Kelly on why he chose not to celebrate Canada Day this year.