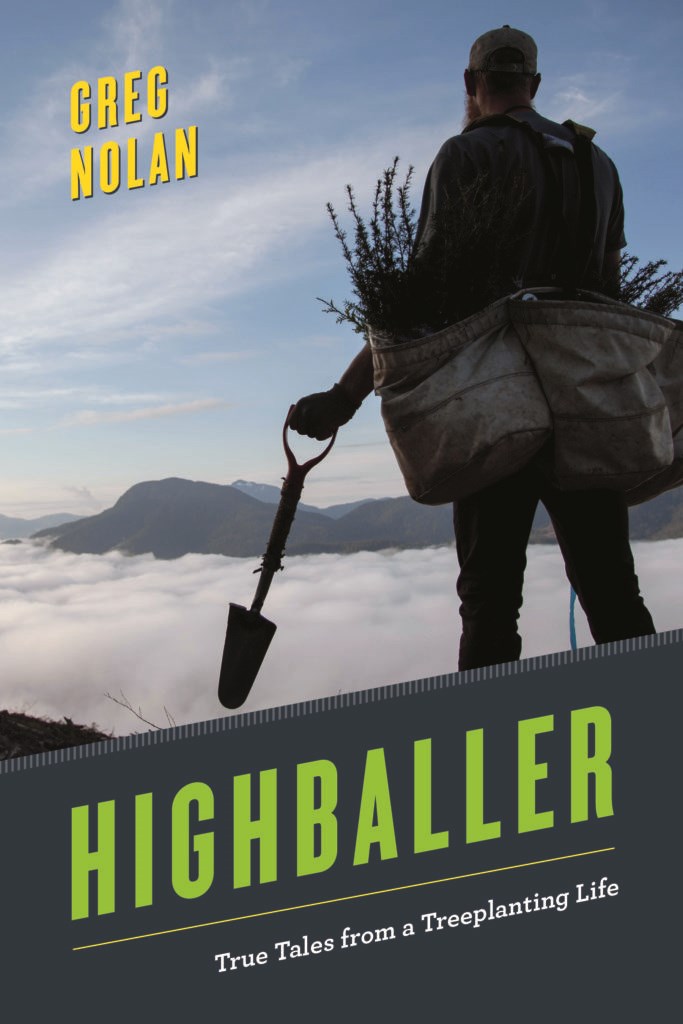

The following is an excerpt from Highballer: Tales from a Treeplanting Life (Harbour Publishing, 2019).

The next morning we came to our first large cutblock for a big pre-work meeting with several high-profile registered professional foresters (rpfs) and a contingent of company checkers. We were assembled to talk about this new concept of hectare-based planting.

This was the first project of its kind in the province; we were to be the very first treeplanting crew to implement it. Apparently only a handful of people had been informed ahead of time that our summer project was an experiment. There was ambivalence, confusion and a posse of shaking heads occupying the front row.

Most of the crew was against the new approach. I was cautiously optimistic.

One of the reasons for the switch in tactics was to reduce what they called “waste.” What they really meant was that they hoped this new strategy would reduce the number of trees that were being systematically “stashed” each year.

“Stashing” is the act of burying, hiding or destroying trees for profit. It can be called a number of things: theft, destruction of property, fraud, etc. It was a contemptible act, one that often resulted in immediate termination. It was also possible to be charged with an offense under the Criminal Code of Canada if the contractor or logging company decided that firing was insufficient punishment. Of course, Barrett had a zero-tolerance policy on stashing.

They believed that stashing occurred as a matter of routine with many treeplanting companies. The hectare-based system removed the motive to stash trees, since one’s earnings were not based on the number of trees planted, but on the amount of land covered.

There was nothing worse than being accused of stashing trees. Every highballer—me included—was often viewed with suspicion by certain people, especially if a tree total at the end of the day was significantly higher than the crew average.

I decided that this contract would be my opportunity to demonstrate once and for all that I was the genuine article, that my reputation as a highballer was well deserved.

During the Williston Lake contract one year earlier, I was determined to end the project as the highest-producing planter in Barrett’s arsenal. Somehow I managed to pull it off. My status as top-shelf highballer remained intact throughout the Too-Much and Mesilinka River contracts earlier in the spring as well. On this project, I was determined to bank more hectares than anyone else on the crew.

The competitive behaviours exhibited by highballers were best characterized as “borderline psychotic.”

By the end of my first day operating under this new regime, I immediately recognized the potential.

Back at camp, James and I assumed our usual roles on bear duty. This made James very happy. When Colette joined us on the roof of the crummy that first evening, people began to talk. Suspected camp romances were fertile ground for gossip in treeplanting circles. But by the end of the first shift, we were all so exhausted from the relentless pace and mid-summer heat, no one really seemed to care, or even notice, that I had a difficult time keeping my hands off of Colette.

I found myself wondering, as I had only a year earlier with Debbie, what would happen between Colette and me at the end of the season. I had a crazy notion that we would carve out a little nook for ourselves back in the city and become a real couple. I suspected that Colette had other plans though. I also suspected that I might never develop the emotional maturity to treat these treeplanting romances for what they really were: escapes, distractions, meaningless affairs.

But for the time being, we were really good together. I tried to focus on living in the moment.

Within a week or so we had caught up with our surveyors. We were chewing through the ground faster than they could carve it up for us. The experiment in hectare-based planting was working out extremely well for many of us. Rather than bag-up a backbreaking number of trees, I found myself carrying lighter loads, which allowed for greater agility and speed. I was planting nearly 1.7 hectares (4.2 acres) per day, and when my area offered large concentrations of naturals, significantly more.

Barrett was paying $250 for every hectare planted. The contract was turning into a major financial windfall. And any suspicions among certain crew members that highballers, like me, were ever guilty of stashing trees, those suspicions were cast aside when they witnessed the vast expanses of terrain being consumed each day.

Midway through the contract, the surveyors had fallen so far behind that when we arrived on a new setting, the perimeter was the only known dimension—no individual areas had been established. This afforded the opportunity to section off our own pieces.

This is where it got interesting.

The surveyors were to come in, after the fact, and run measurements on the areas we defined ourselves. On one such block, I was the first to arrive and was instructed to carve off enough ground to last three or four days. Though the new ground appeared to be one massive clearcut, it was actually a link in a long chain of cutblocks that extended five hundred metres up the side of a mountain, and at least four kilometres further down the valley.

Feeling ambitious and wanting to test myself, I made a bold move: I laid claim to nearly 50 per cent of the first cutblock. I had a good feeling that the surrounding forest had thrown off a generous dusting of seeds over the previous summer and that the winds placed most of them directly on my piece generating carpets of lush, healthy naturals throughout.

The scope of my new area was daunting. It encompassed three deep ravines—hundreds of metres apart—running vertically from the timberline above, to the main access road below. Unsure if I could even put a dent in the area over the course of a four-day shift, I bagged-up with five hundred trees and set off on a reconnaissance plant to see what I could see.

A “reconnaissance plant” is an exploratory run where a treeplanter plants a single line of trees along the entire perimeter of his or her area, with the exception of the very front. This is performed in order to evaluate the terrain; to ascertain its various changes, challenges, and advantages.

Before I was able to plant my way to the top of my new area, I noticed two trucks had pulled in on the road below. It appeared that I was already generating controversy with the size of my piece of land. Within a few minutes Ron and Kelly came into view, huffing and puffing, having made the climb to give me a piece of their mind; to inform me that I was “out of my fucking mind.”

Kelly was pissed off. He went into a bit of a rant, informing me that if the surveyors arrived at some point during the shift, their first order of business would be to subdivide my area several times over. Ignoring Kelly I turned my attention toward Ron and demanded that he have a little faith in me. I needed Ron to give me at least two days to see how far I could get before sending in reinforcements. Ron agreed, saying, “I’ll guard dog it for now, Non-Stop, but if you can’t take out a goodly chunk by the end of tomorrow, expect company pal,” That’s exactly what I needed to hear.

That’s what made Barrett’s company great: managers like Ron who had your back when you needed them most.

I watched Kelly and Ron argue as they descended back down the mountain toward their trucks. Looking out over the vastness of my piece, I knew I really needed to up my game if I was to plant the entire area in only four days. I also needed a healthy population of naturals, distributed over large areas, and from where I stood, I wasn’t seeing them. But the land was clean, the slash was light and the soil was yielding. It was an extremely fast piece of ground.

It took me the better part of two hours and five hundred trees to complete my reconnaissance run. I estimated that my area was at least ten hectares (twenty-five acres). Running the math, dividing ten hectares by four days, I realized that I would need to plant the equivalent of five football fields per day. I had already blown through a quarter of my day and had barely scratched the surface.

At the end of day one, after having planted 2,400 trees, I looked down from the top of my piece. There were people packing up their gear on the road below. I couldn’t make out who they were. I couldn't discern whether they were even male or female. I knew I had made a serious error in judgement. The distance from the top of my piece to the bottom road was still the better part of a half a kilometre.

I had bitten off far more than I could chew. Admitting this to Ron and Kelly would be a humbling experience.

While Colette and I were cuddling in bed later that night, she informed me that word had gotten out that I had lost my mind; that I had carved off more land than the entire company could plant in a week. She also heard a story that I had threatened to brain Kelly with my shovel if he ever set foot on my land again. Stories tend to get exaggerated in treeplanting circles.

Colette was on Kelly’s crew. They were headed to the same valley early the next morning to occupy ground farther down the road from me. Being the focal point of controversy, I knew that a lot of eyes would be monitoring my progress. And I would be on full display for everyone to see, having occupied an area that was elevated higher than everyone else in the valley.

The pressure was most definitely on.

Greg Nolan worked in the silviculture sector for twenty-seven years in various capacities—treeplanter, quality control, foreman, project manager and finally as a contractor serving as co-owner and operator of Rainforest Silviculture Services Ltd. He currently resides in Victoria, BC.

SWIM ON:

- Jennifer Butler also shone a light on a group of remarkable people - in this case, all women - who built and thrived in a remote BC community.

- Speaking of treeplanting, Daniel Marshall encountered a very strange grove of Garry Oak trees far, far from where you might expect.

- Forestry will always be crucial, but Bob Price reveals another emerging economic engine in BC's interior.