Editor's note: the following is an excerpt from City in Colour by May Q. Wong, a remarkable collection of stories that illustrate Victoria's vivid multicultural history - including Canada's oldest surviving synagogue. Full copyright information follows the excerpt.

Perhaps the remarkable story . . . of Canada’s oldest surviving synagogue provides evidence that the sad and tragic history of Jews living in a gentile society is not inevitable. It offers . . . proof that another kind of relationship is possible . . . [one] . . . characterized by “hearty goodwill and brotherly feeling.” —The Scribe

The story of Canada’s oldest surviving synagogue started in 1858, when a scattering of Jews came to the Colony of Vancouver Island among the first boatloads of gold seekers. They came from as far away as Australia, the British Isles, and Europe, many via California, lured by opportunity and adventure. A few joined the trek to the Fraser River goldfields to try their luck, but many of the ones who had first tarried in the gold rush towns of California recognized that the surer way to make money was to supply the gold miners.

The first meeting of the fledgling Jewish community, in Kady Gambitz’s store in August of 1858, was held to find a location for religious services for the high holidays. The notice in the newspaper the next day was read as far away as New York and San Francisco. On June 5, 1859, the Victoria Hebrew Benevolent Society was constituted, with A. Blackman as president. It was the first such organization in western North America.

At the end of that month, the society held its first fundraising ball, where the band of the HMS Tribune “discoursed gentle music to the strains of which all tripped gaily on the light fantastic toe till daylight did appear.” From the very beginning, the newspapers were very supportive of the Jewish community, reporting on its activities in the most positive terms.

The next order of business was to establish a cemetery. Located on Cedar Hill Road, the location was consecrated on June 5, 1860, as the first Jewish cemetery in Western Canada, and it is still in use today. Nine months later, Morris Price, a merchant, was killed at his store on the mainland. A member of the Masonic fraternity, his body was taken care of by the local lodge until it was transported to Victoria for burial. His service included both Masonic and Jewish traditions.

Significantly, when Victoria’s Masonic Lodge No. 1085 was formed in March 1859, the Jewish community was well represented among the twenty-one founding members by A. Blackman, J.P. Davies, L. Franklin, K. Gambitz, L. Lewis, and A. Phillips. At its inaugural ceremony of Constitution and Installation of Officers on August 20, 1860, both Franklin and Gambitz were elected as officers. Other members of that same Lodge were Robert Burnaby, the first Past Grand Master and president of Victoria’s Board of Trade, and Amor de Cosmos, elected as lodge secretary, who would later become the province’s second premier (1872–1874), while simultaneously serving as British Columbia’s member of Parliament in Ottawa (1871–1882).

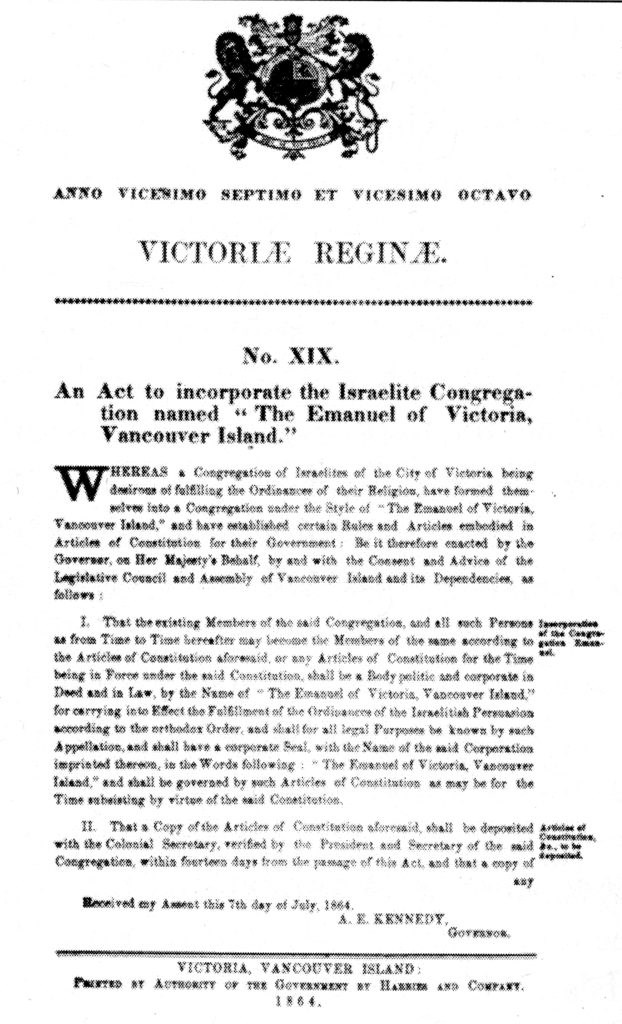

In 1861, an attempt to establish a Jewish congregation failed. However, the committee persevered and by the end of the following year, there were enough people to rent a hall for worship and meetings; purchase benches to be subscribed to by users; elect officers, including David Shirpser as the first president; draft a constitution and bylaws with instructions to obtain an official Colonial Charter of Incorporation Act; fund a shochet (ritual slaughterer); and establish a five-person building and fundraising committee. The congregation of about 100 souls approved the construction of a twelve-by-twenty-one metre building that would sit 350 people.

In a notice printed in the Daily Colonist newspaper about the decision to build a synagogue, the announcement was also made that “Sir Moses Montefiore and Baron de Rothschild be . . . honorary members of the first Jewish Congregation in her Majesty’s Possessions on the Pacific Coast.” While this brazen attempt to solicit funds from the named individuals did not succeed, by the end of June 1863, the fundraising committee had over 200 pledges. Amounts ranged from $2.50 to $150, adding up to almost $5,000, from local Jewish families as well as from their originating communities. The Franklin brothers donated $100, a significant contribution. Many of the donations, and some of the larger amounts, came from the local non-Jewish community—an indication of how well the Jews were accepted in Victoria.

The architecture firm of Wright and Sanders was hired to design the synagogue, which features the Romanesque Revival style then popular in Europe and early Jewish communities in eastern North America. The building contract was given to D.O. Stevens.

Although the building was not completely finished, the congregation chose the first day of June 1863 to hold the cornerstone-laying ceremony. There was, however, a rain delay, and on June 2 it seemed the whole community came to witness the pageantry. The event was reported in glowing detail in the Daily Colonist newspaper.

Community Leaders: The Men

- Two of the earliest arrivals were Alexander A. Phillips, the first recorded Jew in Victoria (April 1858), who established the Pioneer Soda and Mineral Water Works, and Frank Sylvester, born in New York, who arrived in July from San Francisco. Sylvester was active in a broad range of community organizations, including Victoria’s Tiger Brigade volunteer fire company and the Natural History Society.

- Bavarian-born Simon Reinhart came via San Francisco and established a wholesale liquor business in Victoria and New Westminster.

- Kady Gambitz, from Nevada City, California, was the owner of a dry goods store who promoted Victoria as the main supplier to miners and as a place for Jewish families to settle.

- Abraham Blackman, from Stockton, California, was an ironmonger and stove merchant, secretary of the organizing committee, and later a lay leader of the synagogue.

- Judah P. Davies was born and educated in London as a rabbi, but after he married, he and his wife decided to seek adventure in Australia and California before settling on Vancouver Island. In Victoria, he established the successful J.P. Davies & Co. Auctioneers.

- Judah’s son Joshua Davies was a partner in J.P. Davies & Co., and took over the business after Judah died suddenly. Joshua was known to have the largest catalogues and fastest auctions. He was an entrepreneur who invested successfully in mining, lumber, and real estate, and used his funds for philanthropy.

- Selim Franklin, son of a Liverpool banker, was also a government auctioneer whose firm helped purchase the lot for the synagogue. He became the first Jew elected to the colony’s Legislative Assembly.

- Selim’s brother Lumley Franklin became the first Jewish mayor in British North America when he was elected in Victoria in 1866.

- Meyer Malowanski was a Hebrew scholar from Russia and a fur trader who became one of the wealthiest men in the colony.

- Lewis Jeretzky, known as Lewis Lewis, was one of the earliest gold seekers in California and the Fraser River. He donated the land for the Jewish cemetery.

- The Oppenheimer brothers, Charles, Godfrey, David, and Isaac, originally came from Germany. They established one of the oldest continuous food businesses in the province.

Community Leaders: The Women

- Pauline Del Banco Lazarus Reinhart, wife of prosperous businessman Simon Reinhart, provided much experienced leadership toVictoria’s Hebrew Ladies’ Association. She had been the founding treasurer (in 1855) of the Ladies United Hebrew Benevolent Society of San Francisco. This power couple was comfortable among the elites of society, attending functions at Government House.

- Cecelia Davies, the youngest daughter of Judah P. and Miriam Davies, organized one of the synagogue’s first fundraisers at the age of seventeen. She was socially active all her life: she was an early member of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, worked for the French hospital, and served on the executive board of the Jubilee Hospital. Like the Reinharts, Cecelia and her husband, Frank Sylvester, would be known for their hospitality, up to the highest levels of society.

- Rebecca Phillips and her daughter-in-law, Sarah Phillips, were both active with the Hebrew Ladies’ Association.

- Later, in the 1880s, when Victoria’s earlier leading families left the city, women like Henrietta Lenz and her daughters Caroline Lenz Leiser and Sophia Lenz Leiser (the sisters married brothers Simon and Gustave, respectively), stepped in as female leaders in the community. Caroline was a founding board member of the Aged Women’s Home and charter member of the Women’s Auxiliary of Jubilee Hospital.

The Hebrew Ladies’ Association

The Hebrew Ladies’ Association was integral to the success and longevity of Congregation Emanu-El. As an orthodox community, the men traditionally made all the decisions and held the finances. From the beginning, however, the men called upon the women to assist in fundraising to help pay the bills; any money the ladies made was handed over to the treasurer.

The women proved their worth with their well-honed organizational skills, social connections, and interpersonal abilities. The year after the synagogue was built, the ladies ordered a wedding chuppah (the canopy under which the bride and groom stand) from London, England, made of Chinese silk. The group provided lunches and suppers at special social events, fed and cared for the Jewish poor and indigent, decorated the sanctuary for special occasions and holidays, and held bazaars. The first community ball, in 1864, was so successful that the public looked forward to attending it every year. When asked, the ladies raised emergency funds, such as in 1885 to repair the cemetery fence when it burned down, and were instrumental in helping to pay off the building’s mortgage, as well as the salaries of the rabbi.

They were not without controversy. Innovations such as adding music into the worship service through singing or with musical accompaniment were desired by some of the younger generation, but resisted strenuously by the older, more orthodox (mostly male) members. Quietly and over a period of years, the young women were successful.

The Hebrew Ladies’ Association was officially established with thirty-two founding members in November 1890. Any Jewish woman of “good moral character”¹³ was eligible to join. In 1863, the congregation had the foresight to purchase the lot adjacent to the building. The ladies took it upon themselves to find the funds necessary to build the Ladies’ Hall, which would include a school, meeting rooms, rabbi’s residence, social hall, kitchen, and lavatories. The building was “fitted with modern adornment and conveniences adapted for comfort and pleasure” and opened in 1893.

After 1907, financial constraints led the congregation to look at the Ladies’ Hall as a cash cow. It was renamed Victoria Hall, and while the ladies could use it free of charge for their continued fundraising efforts, the space was rented to church and athletic organizations. Over time, the building deteriorated and it was demolished in 1970. The vacant area was rented out as a car lot for an adjacent garage. The Hebrew Ladies’ Association dissolved as an independent organization in 1912; the remainder of the group became known as the Ladies Auxiliary of the congregation.

In 2003, a new three-storey building was built at the same location, dedicated to “Jewish education, community service and fellowship—no doubt in keeping with the Hebrew Ladies’ original intent.”

Reprinted with permission from City in Colour by May Q. Wong, 2018 TouchWood Editions. Copyright © 2018 by May Q. Wong.